Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 3 September 2015

Kieran’s Little Book of Cork

The Little Book of Cork is a new book penned by myself and published by History Press Ireland. It aims to be compendium of fascinating, obscure, strange and entertaining facts about Cork City. Here you will find out about Cork’s buildings and businesses, its proud sporting heritage, its hidden corners and its famous (and occasionally infamous) men and women. Through its bustling thoroughfares and down winding laneways, this book takes the reader on a journey through Cork and its vibrant past, recalling the people and events that shaped this great city. A reliable reference book and a quirky guide, this can be dipped into time and time again to reveal something new about the people, the heritage and the secrets of Cork.

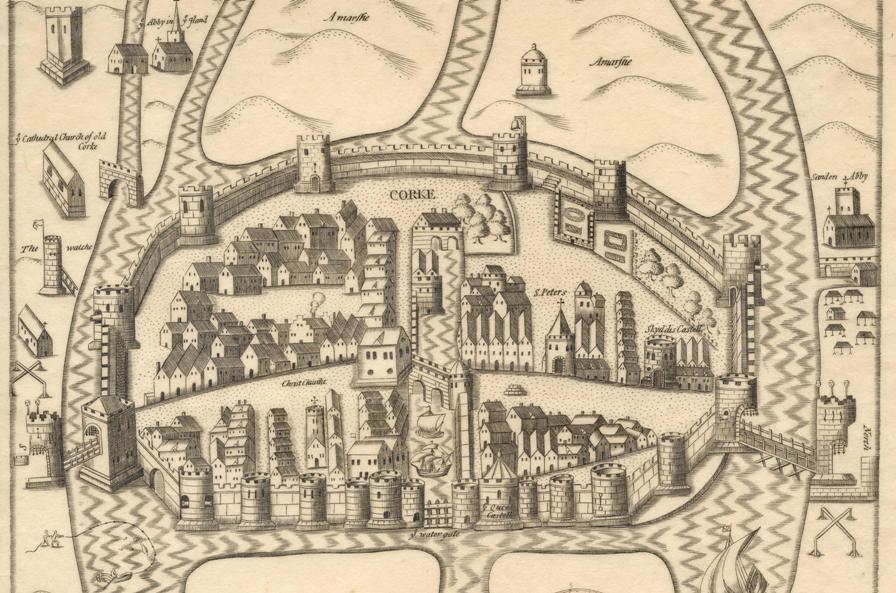

The book has nine chapters. This book begins by delving into the multiple phases of Cork’s development, its tie in to wider Irish history and to a degree how Cork branded itself through the centuries. From the creation of the first port, the city’s coat of arms, to building international confidence as one of the self-proclaimed Venices of Northern Europe, Cork’s historical development and ambition knew no bounds! However, certainly colonists such as the Vikings and Anglo-Normans and immigrant groups (and eventually citizens in their own right) such as Huguenots and Quakers led the settlement to have a role in the wider North Atlantic trade and beyond. All were involved in physically altering the townscape, constructing new buildings and quays and improving the interface with the river and the sea. Some key events such as Cork’s role in the Irish War of Independence in the early twentieth century also led to changes to the city’s fabric. The Burning of Cork incident led to many of its main street buildings, City Hall and Library being destroyed. The city rose from the ashes with a rebuild plan plus also strategies for the growing population and their requests for new housing areas.

Chapter 2 focuses on the array of public spaces and buildings that the city possesses. You can get lost in and around the multiple narrow streets and broad thoroughfares. Every corner presents the visitor with something new to discover. The pigeonfilled medieval tower of the Augustinian Red Abbey and the ruinous room of an old Franciscan well are rare historical jigsaw pieces that have survived the test of time. The dark dungeon at Blackrock Castle, with its canon opes, dates back to 1585 whilst the star-shaped structure of Elizabeth Fort has stonework stretching way back to the early seventeenth century. The city does not have much eighteenth century built heritage left. What does exist such as the Queen Anne ‘Culture House’ on Pope’s Quay, represents an age where Dutch architecture was all the rage. A high pitched roof and elaborate and beautiful brickwork combines to make a striking structure. The legacy of the city’s golden age of markets is present in the English Market, written about and critiqued since 1788.

Many architects have come and gone over the centuries but the rivalry of The Pain Brothers and the Deane family in the early nineteenth century inspired both families to excel in the design of some of the most gorgeous stone-built buildings from banks to churches to the quadrangle of University College Cork (UCC). All were embellished with local limestone, which on a sunny day, when the sun hits such a stone, lights up to reveal its splendour and the ambition of Ireland’s second city. The settlement is also a city of spires linking back 1,400 years to the memory of the city’s founding saint, Finbarre. The old medieval churches of St Peter and Christ Church are now arts centres but many elements of their ecclesiastical past can be glimpsed and admired. Couple these with the beautiful St Anne’s Church tower and the scenery from the top of its pepper pot tower, the nineteenth-century splendour of the spires and stained glass of St FinBarre’s Cathedral and the sandstone block work of SS Mary’s and Anne’s North Cathedral, and the visitor can get lost in a world of admiration and wider connections to global religions. Then there is the determination that led the city to also possess the longest building in Western Europe – the old Cork Lunatic Asylum or Our Lady’s Hospital and the tallest building in the country – County Hall, and only in recent years surpassed by the Elysian Tower.

Then there are the buildings which belong to the people. The current City Hall, the second building on the site, is the home of Cork City Council, formerly Corporation, which was established in Anglo-Norman times. The building is a memorial to the first building, which burned down in 1920, and to the memory of two martyred lord mayors, Terence McSwiney and Tomás MacCurtain. Terence died on a hunger strike and Tomas was shot in his house in Blackpool, both dying for the Irish War of Independence cause. The train station, Kent Station, also links through its name to Irish Easter Rising martyr, Tomas Kent. The station is the last of six railway stations, which travelled out into the far reaches of County Cork.

The Little Book of Cork is available in any good bookshop.

Captions:

808a. Front cover of Little Book of Cork (2015) by Kieran McCarthy, published by History Press, Ireland.

808b. Re-enactors at Elizabeth Fort, recent Cork Heritage Open Day