Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 12 June 2025

Making an Irish Free State City – The Making of Cork Public Museum

Culturally, socially and economically, the City of Cork evolved in the early years of the Irish Free State. However, one of the surprising happenings during that time was the closure of the public museum in 1924. The story of how the closure happened is now the focus of a recently launched exhibition in the current museum, which offers insights into the early origins of Cork Public Museum from the 1910s to the 1940s.

Entitled “1945 Uncorked” the new exhibition celebrates the 80th Anniversary of Cork Public Museum. The Museum Studies students at University College Cork have carefully assembled a new exhibition on the early origins of Cork Public Museum with curator Dan Breen and the amazing staff of Cork Public Museum. This unique collaboration has run for several years now, and it is the only one of its kind in Ireland. In fact, there are few other opportunities like it worldwide, and the programme’s assembly of Irish and international students demonstrates that.

A museum in Fitzgerald’s Park sprung from the highly successful international exhibition in 1901-2. In 1904, the exhibition committee handed over the exhibition grounds to the Corporation of Cork to be developed into a park for Corkonians. The work of clearing up the grounds and of removing the larger temporary buildings first received the attention of the exhibition committee. The Corporation even appointed a special committee under the chairmanship of Sir Edward Fitzgerald. The committee directed their energy towards the reclamation of the grounds until laying the most into formal garden treatment finishing with the removal of the high hoarding which obscured the view by the erection of ornamental iron railings in their place opening up the view of the public to the park itself.

On 22 March 1906, a meeting of the Fitzgerald Park Committee was held for the purpose of considering the following motion, notice of which had been given by Alderman Meade: “That we declare our willingness to vest the Park and the Shrubbery House in the Corporation of Cork, provided they agree to levy a rate of a half a penny in the pound annually for their upkeep and maintenance, and that the house be used as a museum”. Sir Edward Fitzgerald Chairman, presided. The motion was passed by a majority on the committee.

The assignment of the park to the Corporation of Cork for the benefit of the citizens also took in the large Shrubberies mansion with the express stipulation that it was to be converted into a museum. The committee expressed the sentiment that the City needed a public museum.

A Museum sub committee appointed by the Corporation turned their attention to the work of fitting up and adapting the old Shrubberies House to its future purpose as museum. Some of the original advisory sub committee were connected to the Raw Materials committee of the Cork International Exhibition. The Museum committee was made up of Professor Hartog, Professor Thomas Farrington, Mr J L Copeman, Mr James Coleman and Mr John Paul Dalton, Honorary Curator. Mr Dalton worked for free in the early stages of planning. One of the first practical steps taken to furnish the museum was the circulation far and wide by the secretary of Corporation Committee Secretary D F Giltinan of many hundreds of circulars amongst the managers of kindred museums and others able and willing to contribute suitable objects either as valuable gifts or loans. Many objects and artworks were given arising out of the call out.

On 22 November 1910, John Paul Dalton, Honorary Curator of the museum, appeared before the Fitzgerald’s Park Committee and noted he had great pleasure in stating that the museum was now ready for opening. Exhibits of the most interesting kind had been put into position into cabinets and objects were still arriving. Amongst the latest exhibits received was an interesting old lithographic stone that was used for printing certificates of examinations in the old school of design and an Elizabethan map of Youghal. These were presented to John Paul from the Crawford Municipal School and its principal Mr Hugh Charde. Mr Dalton also highlighted that there were three quaint paintings given by his brother Mr Frank Dalton. which had apparently being in some historic Cork mansion. One represented the South Mall with a statue of King George II on horseback, another showing a part of the city and another was a painting representing Queenstown (now Cobh) and Cork Harbour. He deemed them all possibly 100 years old.

In a separate Cork Examiner article is a nod to the delivery and receipt of a very finely carved representation in stone of the arms of the city, dating probably from the early part of the 17th century. The slab was formerly part of the Old Guard House, which stood in Blackpool, near the sanctuary of the old St Nicholas Church now stands. On the demolition of the Guard House the slab came into the possession of Mr Edmond O’Flynn, who presented the stone to the Museum.

The Shrubberies House was renovated and retrofitted by the Corporation’s City Engineer J F Delaney. On 22 December 1910, the Cork City Museum was officially opened by the Lord Mayor of Cork Cllr Thomas Donovan. In the buildings, there were objects presented comprising “artworks, curios, industrial art specimens, books, money scripts, etchings, pictures etc”.

On 17 December 1912, John Paul Dalton’s death was announced in the Cork Examiner atthe age of 46. The newspaper adds that John was well known in Cork literary and artistic life. Amongst his published works were Poems: Original and Translated and Sarsfield at Limerick, a cantata produced some years ago in Cork. He was a contributor to literary magazines an art connoisseur and an antiquary.

John Paul’s premature death in 1912, attributed to the stress of running the struggling institution, exacerbated these issues. Unfortunately, turmoil from the War of Independence and the Civil War only worsened this museum’s hardships. It closed its doors in 1924. For the next twenty years, the citizens of Cork had no public museum to preserve and share Munster’s heritage.

More next week…

June 2025 Historical Walking Tours with Kieran (All free, two hours, no booking required).

Saturday afternoon, 21 June, Ballinlough – Antiquities, Knights, Quarries and Suburban Growth; meet inside Ballintemple Graveyard, Temple Hill, opp O’Connor’s Funeral Home, 1pm.

Sunday afternoon, 22 June, Blackpool: Its History and Heritage; meet at the square on St Mary’s Road, opp North Cathedral, 1pm.

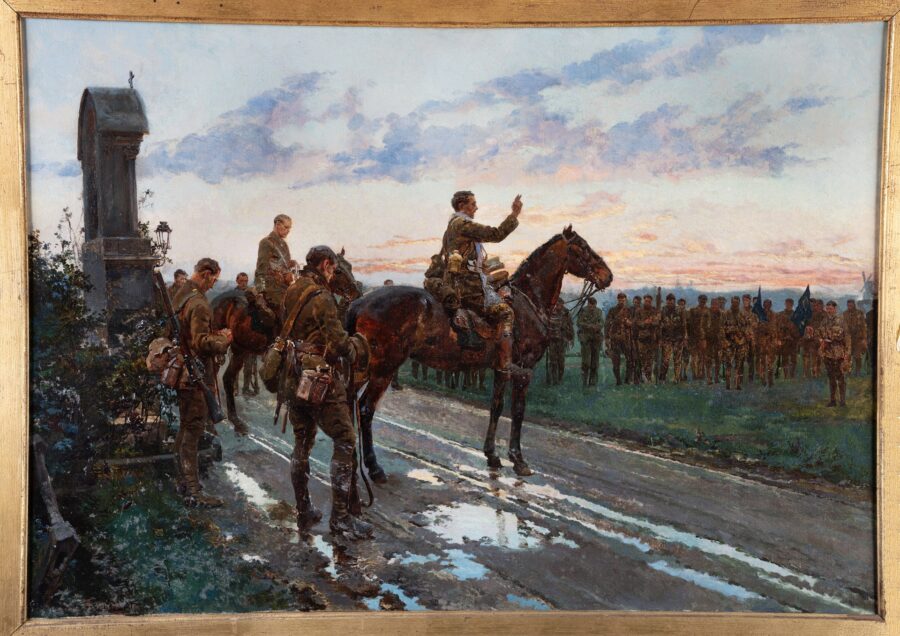

Caption:

1308a. Fitzgerald’s Park Municipal Museum, 1910s (source: Cork Public Museum)