Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 3 July 2025

Making an Irish Free State City – A Public Museum Opens, 1945

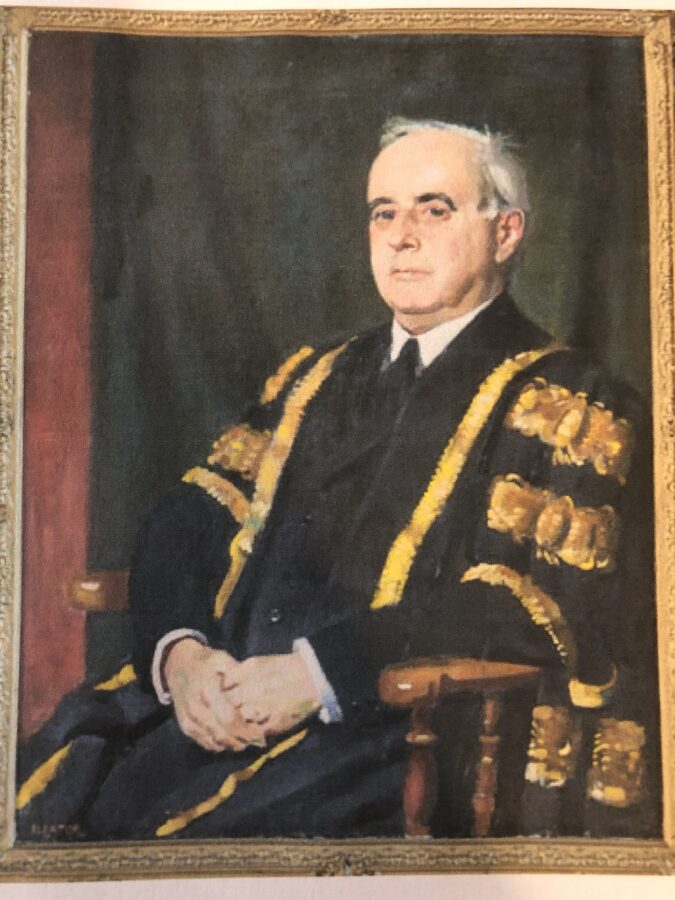

Continuing from last week, Cork Public Museum opened on 4 April 1945. On the day of the formal opening, the museum hosted guests of honour, which included Minister for Posts & Telegraphs, P J Little and UCC president, Alfred O’Rahilly. The No. 2 Army band provided entertainment and only invited guests were allowed into the museum at the opening ceremony.

In declaring the museum open, the Minister referred to co-operation between the university, the public bodies of Cork City and County, and individual patrons in establishing the Museum. He noted the co-operation as very inspiring and called for keeping the focus on the city’s local history; “It should become more and more a source of legitimate pride to all such patrons, that rapid progress should be made in revealing all these relics of their past to the people and to the world. In these activities too, they should aim rather at decentralisation, so that that the very real interest of local history should add as much colour as possible to the exhibits and records”.

In the days that followed the opening there were write-ups praising the museum committee and the new museum. On 6 April 1945, an editorial in the Cork Examiner articulated the importance of understanding Cork’s history as a layered suite of histories and memories; “The re-opening of the Cork Museum in Fitzgerald Park after a lapse of more than twenty years should be regarded as a landmark in the history of the municipality and its surroundings by all who believe in the preservation of a memory of the past coupled with a realisation of the present. Much can be gained by the study of the past if people are prepared to approach it is the proper spirit, without violent biases one way or the other Cork, like every city, does not owe its present status and condition to any one generation”.

Michael J (MJ) O’Kelly (1915-1982), was appointed curator of the new Cork Public Museum. Abbeyfeale-born Michael Joseph or also known as Brian originally trained as an architect in UCC before he was inspired by his work as a surveyor under Professor of Archaeology at UCC, Seán P Ó Riordáin at his dig site at Garranes Ringfort. Michael changed career and pursued a BA and MA in archaeology and on his MA graduation was appointed the museum curator post.

In the souvenir booklet published in 1945 to mark the opening, M J O’Kelly wrote a detailed description of the building. He described that the entire upper floor, staircase, hall and vestibule were repaired and renovated in pursuance of a scheme drawn up by the City Engineer and approved by the Museum Committee. This work, which also included many structural alterations, was paid for out of the first moneys granted for museum purposes by the Corporation of Cork.

In addition, when the management of the Museum was handed over to University College, it was found that further essential work was necessary. This included the installation of heating and lighting systems throughout the building as well as the complete renovation of two ground-floor rooms not envisaged in the original scheme. These rooms were converted into an office and workshop and fitted up accordingly.

In the souvenir booklet, M J O’Kelly outlined that three showcases, as well as a very miscellaneous collection of exhibits, survived from the old museum, and except for these the building was without furniture or fittings of any kind. The provision of an adequate number of showcases was a difficult task to secure in view of the prohibitive cost and unsatisfactory nature of the materials available during the Secon World War. Many of the cases were provided on loan from the museums in UCC. One or two others were purchased, while a bow-fronted case in the Hall was generously presented by the Lord Mayor, Councillor Seán Cronin.

In preparation of the first exhibition, M J O’Kelly describes that the first exhibition was focussed on the history and development of Cork city. An attempt had been made to illustrate the successive periods in the city’s growth and development by a series of exhibits gathered together from many sources. Much of this material had been generously lent by University College, by the Corporation, and by numerous business firms and others. In addition, they received a number of permanent gifts. The names of the large number of donors were published on the souvenir booklet.

In the booklet M J O’Kelly thanks the donors and comments that the museum committee gave itself a short time to assemble its exhibits: “It has been no easy matter, then, in the short time at our disposal to assemble, prepare and label suitably all the material which is now on display, and we are very conscious indeed of the shortcomings from which the exhibition as a whole suffers would ask you to remember that the Museum is a new project as yet very much in its infancy, and that it will be some before it is fully equipped and provided with adequate collection of exhibits. We hope that all those who can do so will come forward and help to build up these collections by lending or present to the Museum any objects of general interest which they have in their possession or under their control”.

M J O’Kelly in his concluding remarks in the souvenir booklet notes that the museum committee’s future aims were about making a case for a really large museum for Cork and the South of Ireland generally with specially trained staff. He noted: “The present building, while been satisfactory for immediate needs, is entirely inadequate for permanent purposes, and if it can be shown, as we hope to do that the project is deserving of wider support, there is no reason why a Cork Museum should not form a part of the post-war scheme for the development of the city. In planning for the future it is our hope that a fully equipped museum will be provided in which every form of art, industry, natural history and science will be adequately catered for by specially trained staffs who will carry out research and field-work; but for the time being we must be content to make the best showing possible within the limits of the money and space at our disposal”.

To be continued…

Cork Public Museum celebrates its 80th anniversary with the exhibition 1945 Uncorked: The Founding of Cork Public Museum. This exhibition opens to the public on 30 May and runs until Spring 2026.

Kieran’s historical walking tours for July 2025 (all free, 2 hours, no booking required)

Sunday 13 July 2025, Views from a Park – The Black Ash and Tramore Valley Park historical walking tour; meet at Half Moon Lane gate, 1pm.

Wednesday 16 July 2025, Cork Through the Ages, An Introduction to the Historical Development of Cork City; meet at the National Monument, Grand Parade, 6.30pm.

Thursday 17 July 2025, Sunday’s Well historical walking tour; discover the original well and the eighteenth century origins of the suburb, meet at St Vincent’s Bridge, North Mall end, 6.30pm.

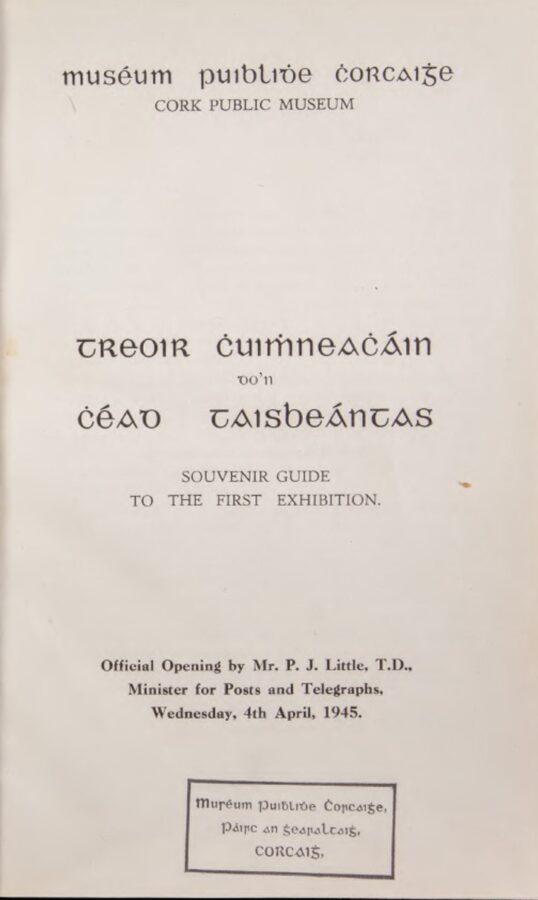

Caption:

1311a. Inside cover page of the souvenir guide to the Cork Public Museum, 1945 (source: Cork Public Museum).