Now a fantastic amenity walkway its original iteration as a railway line was a costly but bold project in mid nineteenth century Cork.

The Initial Idea:

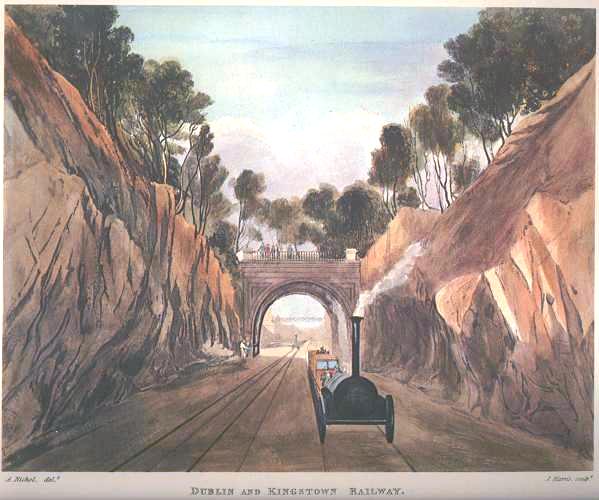

It was in 1835 that the plan for a Cork to Passage railway was first proposed by Cork based merchants. Its creation was influenced by the Dublin and Kingstown rail line, which was being constructed at the time. Indeed, there were noticeable similar designs between the Dublin line and the Cork proposal, mainly because the same engineers were working on both – namely Charles Vignoles and Sir John MacNeil.

By the time the Cork Blackrock and Passage Railway line was built it was the third railway line to open in the country and the first in the south of Ireland. Such a latter accolade was important to the burgeoning middle classes of Cork, both Protestant and Roman Catholic, who were very determined on Cork’s engagement in developing Cork Harbour infrastructure to help trade and move goods from the city to the lower harbour with ease.

Passage West had become an important harbour port for large deep-sea sailing ships whose cargoes were then transhipped into smaller vessels for the journey up-river to the city. This transhipment would be faster by train. With the establishment of a dock and ship-yard in Passage West in the nineteenth century, many merchants became ship-owners, and carried on an extensive trade in their own vessels. Three of these individuals were well known entrepreneurs, William Parker, Thomas Parsons Boland, and William Brown.

Legislation & Planning the Line:

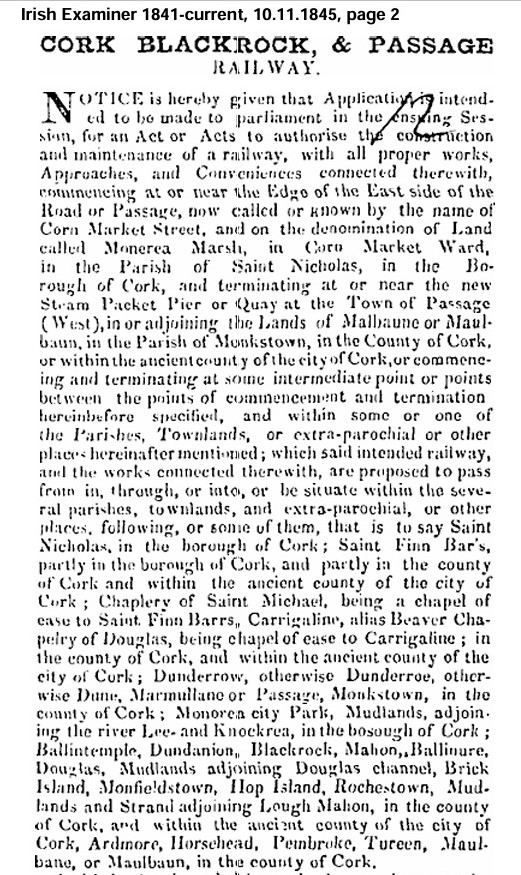

Indeed, in the summer of 1835, a committee was set up to plan the railway and the Harbour Board, the British treasury and other bodies were approached for financial support. The matter was deferred as it was deemed too late in that year to apply for an Act of Parliament to authorise the line.

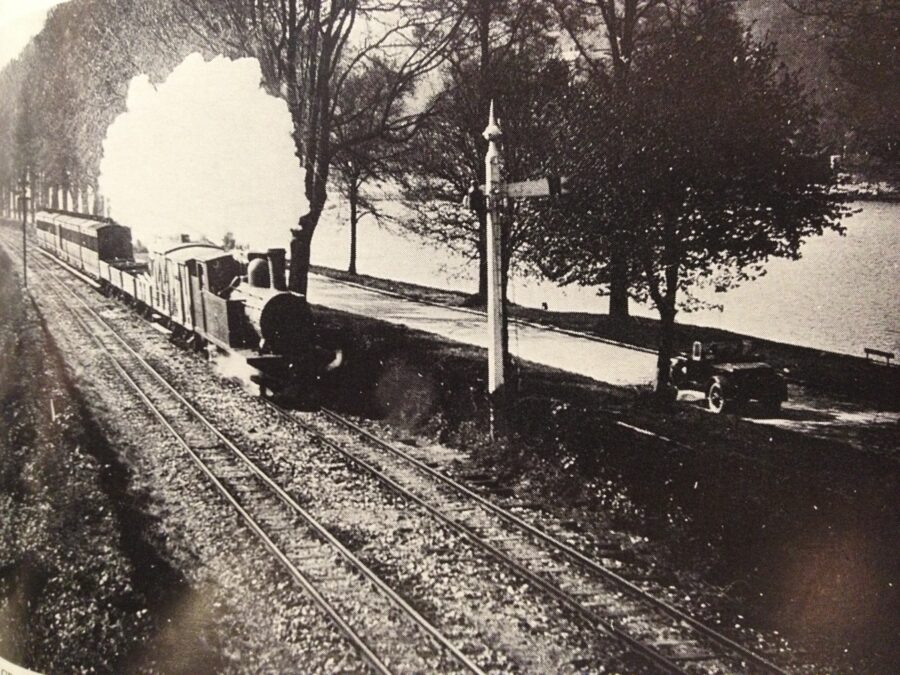

Wexford-born Charles Vignoles was appointed engineer of the venture. In 1825 Vignoles surveyed the proposed London and Brighton Railway and the initial surveys for the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. The initial plan for the Cork to Passage West by Vignoles in 1836 was for the railway to go from Cork City through Douglas and to build a tunnel underneath Langford Row. However, it was eventually decided that it was cheaper and more level to construct the line along the south bank of the Lee. The proposed line would run close to the south of the dock-like Navigation Wall (now the site of the Marina walk) on reclaimed land, remain close to the river, disappear into a specially blasted out Blackrock cutting, crossing Douglas estuary on a cast iron bridge and onto Passage.

Preparatory works immediately began at the Cork site and in 1837 the Passage Railway Bill was passed in the Westminster parliament. However, by 1838, the project was shelved due to the difficulty of raising finance and the worsening social conditions at the time. In addition, the main shareholders had lost interest and wanted their investments returned.

It was only in the mid-1840s that the project was resurrected. This was due to the fact that other railways were being planned for the city. In addition, in 1845, legal sanctions were sought for three railways; Cork-Passage Railway, Cork, Blackrock, Passage and Monkstown Railway, and Cork-Kinsale Railway. In the case of the first two requests, their plans were amalgamated to form the Cork, Blackrock and Passage Railway Company in 1846. This created a share-holding system, which was of great benefit to raise financial investment of which in time £226,663 was subscribed.

The relevant legislation was passed in 1846 and in September 1846, the company’s engineer, Sir John MacNeill was employed to complete initial survey work. Dundalk-born MacNeil was a prominent Irish engineer who in 1834 set up his own consultancy, based in London and Glasgow. During the late 1830s and early 1840s, MacNeill dedicated his work to his native Ireland. He worked on various railway projects, including the Dublin and Drogheda Railway, Much of Ireland’s modern railway network still go along routes he suggested. For example, the Dublin-Belfast railway line follows the line of the Dublin and Drogheda Railway along the coast.

In truth, MacNeil was a big name in engineering circles to have involved in Cork. Patrick Moore won the Cork contract for the first six miles of the line between Cork and Horsehead. The tender being £38,000 and work began in June 1847. One of the first problems encountered involved the acquiring of enough finance for purchasing land for the project itself. Land was expensive – much of it was bound up within small and large estates. It was decided by company officials that the company should also look to the future and buy land that would be used if an expansion occurred. The cost can be estimated at £21,000 per mile.

Starting the Work:

In a very notable turn of events, the turning of the first sod was carried out by Lady Elisa Deane at a site adjacent to the Deane Family residence at Dundanion. Her husband Thomas, a leading architect in Cork City and who a major supporter of the rail project, was away. The eminent Illustrated London News depicted this scene on 26 June 1847 – the interest by such a paper in the rail project was another accolade to achieve.

Due to the fact that the construction was taking place during the Great Famine, there was no shortage of labour. Large numbers of unemployed people were attracted to the construction areas. However the selection process was not straightforward. Trouble arose on more than one occasion with people who were not selected for jobs. For example, on 21 June 1847, 70 men were selected or hired. A week later, 600 of those who did not get a job invaded the site. To counter the problem, 450 men were taken on for the erection of the embankment at the Cork end of the line. Another 80 were employed on digging the cutting beyond Blackrock towards Douglas estuary.

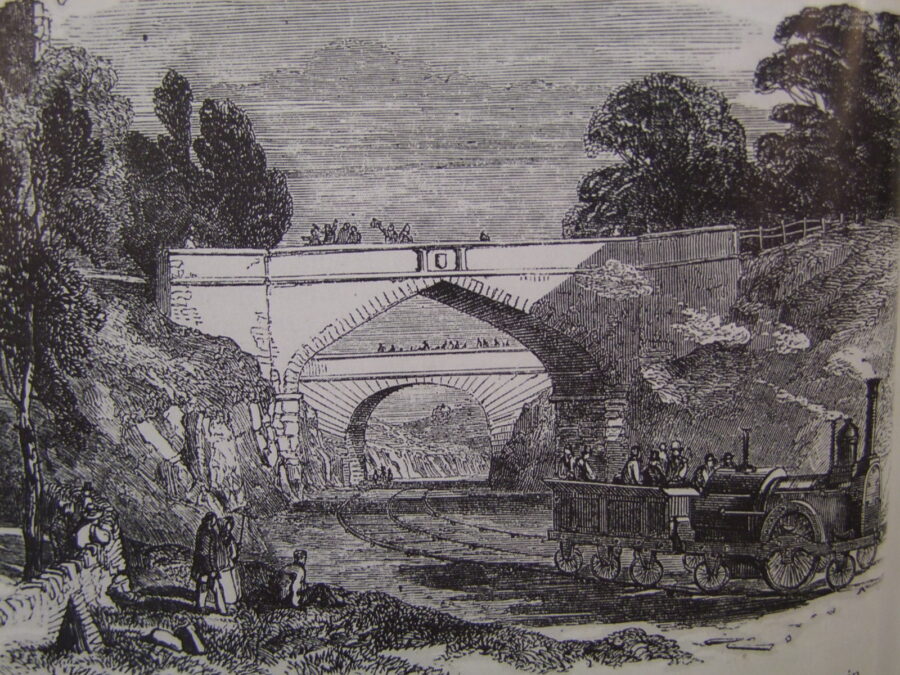

On one of the arched bridges at the Blackrock cutting is a large carved stone with the inscribed year of 1848 denoting when this solid and architecturally impressive bridge over the developing railway track was completed and unveiled. The Blackrock cutting as well was the most difficult part of the project to dig out through the rock with the use of gunpowder.

With the recent conservation works one can also see the other two bridges in the Blackrock cutting clearer, and see their high end stone work. Indeed if one looks closer from the Skehard Road side in the present day towards Blackrock, one can see that the old (Ballinsheen) railway bridge has marked pillars coming out from it to show a heightened status as if the Blackrock cutting was a site to show off elements of engineering and construction.

For a cohort of Cork’s mercantile classes, the railway project was a culmination of almost 15 years of ambitious lobbying and assembling serious funding from Westminster and a serious crowd-funding from other local and regional merchants. The cost of construction was £21,000 per mile – and the line was just over six miles from Cork to Passage.

For another cohort of Cork society who were suffering from the ravages of Famine, perhaps they had little or no opinion – the 5,000 people crammed into Cork Union Workhouse built to host 2,000 people on Douglas Road or the 4,000-5,000 recorded beggars on the streets of Cork.

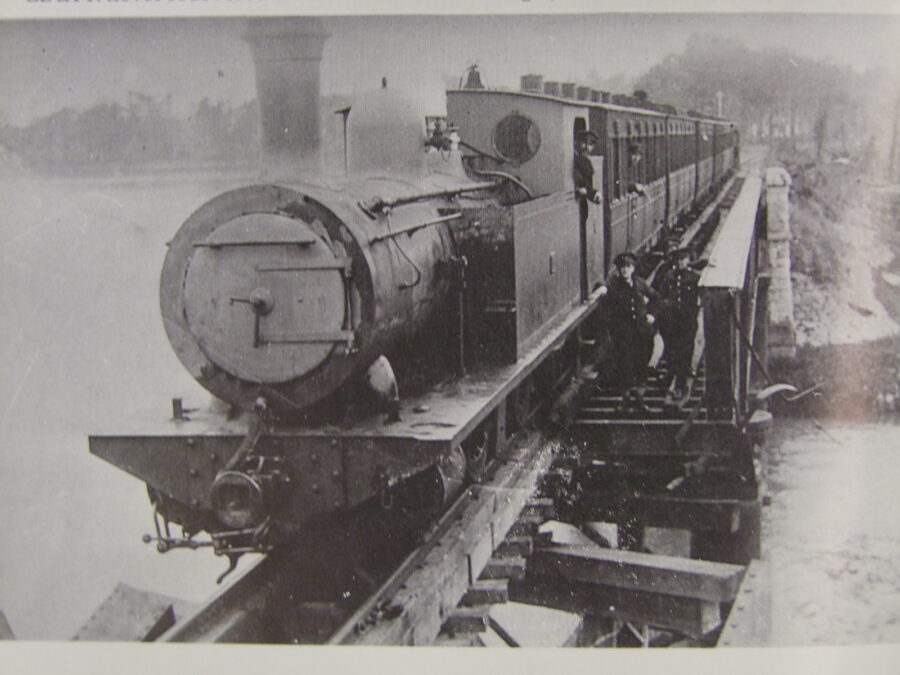

On 27 April 1850, the first trial run of a locomotive took place. The six and half mile trip from Passage to Cork took 17 minutes. A week later, a second trial took place this time from the city end of the line. This event was also captured in the Illustrated London News, on 25 May 1850. An engine pulled a first class carriage, which carried the directors of Cork, Blackrock and Passage Railway and a group of merchants. The outward journey took 17 minutes and lasted just over ten minutes on return.

Opening the Line:

The line was opened to the public on Saturday 8 June 1850 and there was a service of ten trains each way at regular intervals. The departures from Cork to Passage were on the hour while from Passage to the city were every half an hour. In addition, fortunately the gradient of the line was small with the highest point being approximately seven metres above sea level and located just after the Blackrock Station. By the end of November 1850, the company had made a surplus of £1,500 and had 20,000 miles run and such was its popularity it had carried 198,747 passengers – 79,106 first class and 119,641 second class passengers.

The entire length of track between Cork and Passage was in place by April 1850 and within two months, the line was opened for passenger traffic. Cast iron rails were used initially and replaced in 1890 with steel rails. William Dargan, a successful railway contractor was employed to complete the final section of the line between Toureen Strand and the Steam Packet Quay at Passage.

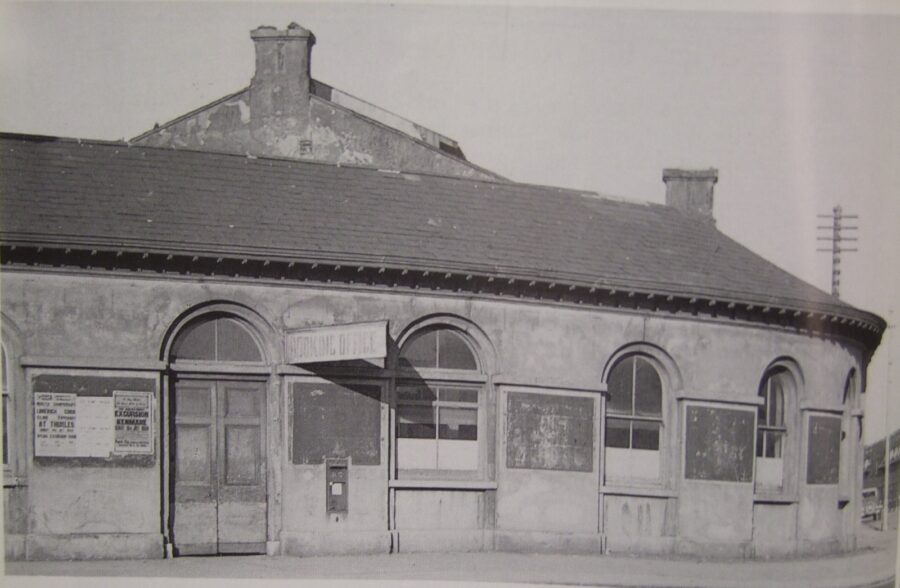

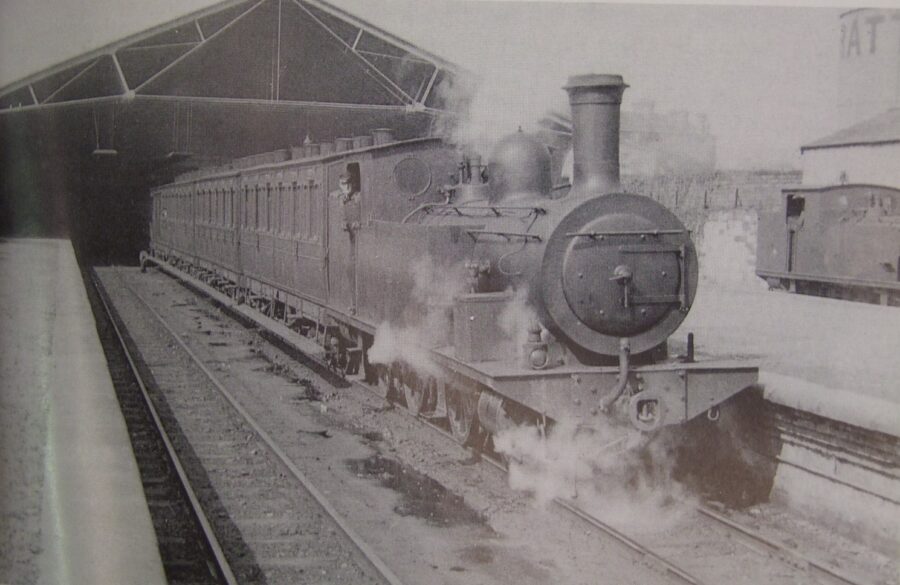

The original terminus was located at Victoria Road. It was a two-storey structure with a corrugated iron roof in three parts, a centre and two sides. Cast-iron columns, manufactured by King Street Iron Works, supported the roof. However, in 1849, a year before the station opened in 1849, the local press began to complain about the station’s location within the city. They argued that the site would interfere with dock development in Monerea Marshes. The line near the station occupied large area of river frontage, which the Harbour Board and Cork Corporation became more and more interested in acquiring.

This problem was only rectified in the Cork Improvement Act of 1868 and in 1872. It was proposed to create a two-kilometre diversion from the metal over-bridge on the Marina, which was to lead the line away from the riverfront along the Monerea marshes to a new terminus west of the City Park Station at Albert Road. This cost was paid for by Cork Corporation. Designed by John Benson, the new Cork terminus of the Cork, Blackrock and Passage Railway’s was opened and completed in 1873. The original Victoria Road terminus also became part of complex. The building now awaits a new use as part of the redevelopment at the former Sextant site compound.

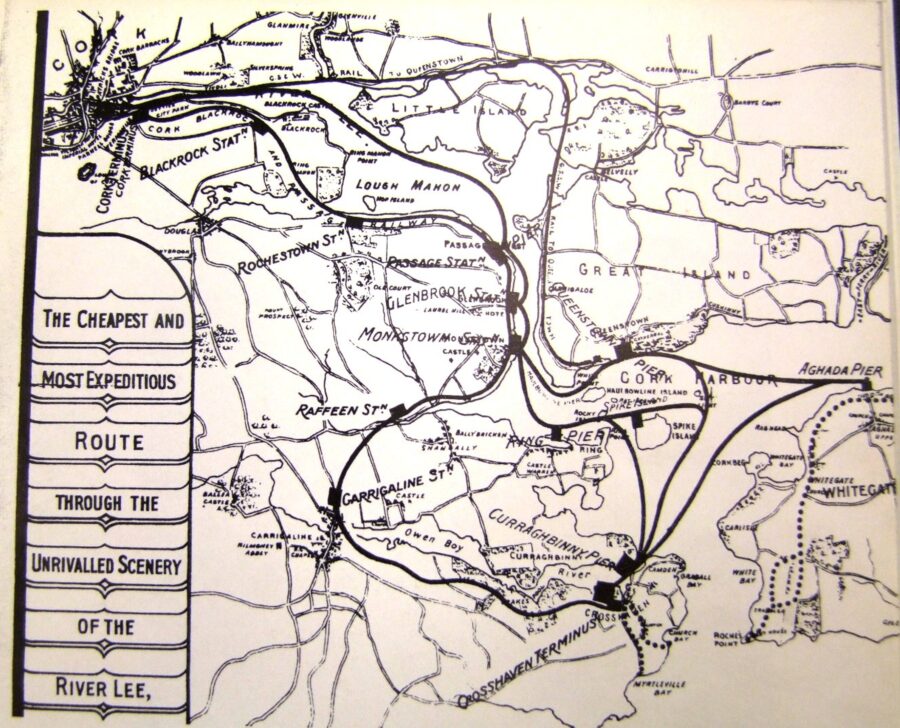

Three new engines along with fifteen passenger carriages were bought from the Sharp brothers of Manchester. In the late nineteenth century, the Cork Blackrock and Passage Railway also operated a fleet of river steamers in competition with River Steamer Company (R.S.C). The Railway Company expanded its fleet in 1881 but it was only when the service was extended to Aghada that profits grew. Steamers left Patrick’s Bridge to stop at places such as Passage, Glenbrook, Monkstown, Ringaskiddy, Haulbowline, Queenstown and Aghada, Spike Island, and Curraghbinny.

Extending the Line:

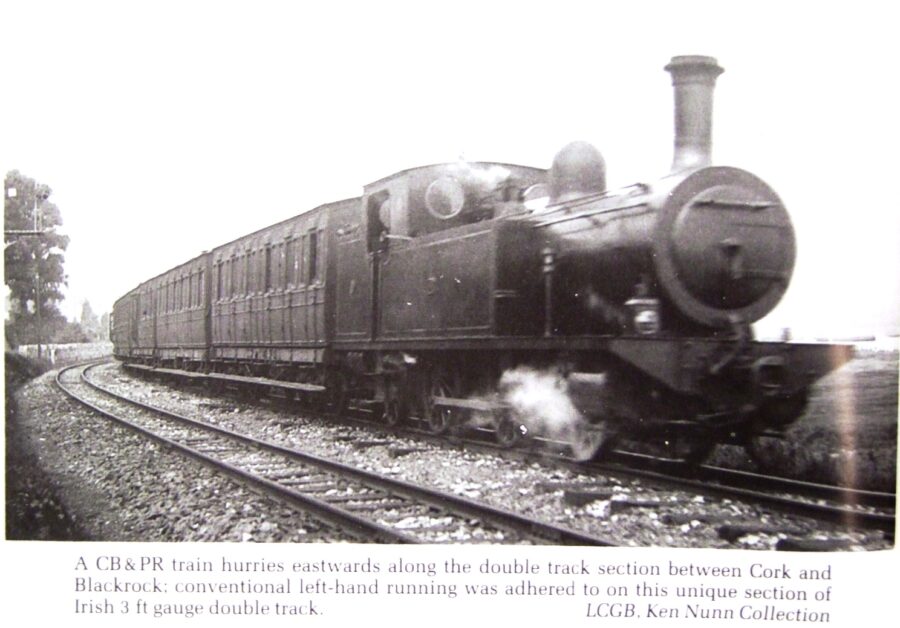

In 1896, an Act of Parliament enabled the company to extend the line as far as Crosshaven. John Best Leith, Scotland received the contract for the regauging of the line. Works began in 1897. A new double track was laid between Cork and Blackrock, the only example of a double track in Ireland at the time.

Challenges in the 1920s:

On 25 February 1924 the annual general meeting of the shareholders of the Cork, Blackrock and Passage Railway Company was held. Sir Stanley Harrington, Chairman, presided and read out a detailed report on the challenges facing the company. Annual AGM reports one hundred years ago and published by newspapers such as the Cork Examiner provide rich material to chart the rise and fall of the railway company.

At the 25 February 1924 meeting Mr Harrington related that a year on from the Civil War the damage on the span on the Douglas Viaduct had been repaired. Signal cabins at Rochestown, Passage and Monkstown had been rebuilt. The Blackrock cabin was in the course of rebuilding. The six carriages, which were burnt out, were replaced by new ones.

However, Mr Harrington’s core focus was on the difficulties to balance the company’s accounts. For several years the deficit on the account was accelerating. Reference is given that one of the serious reductions to profits was the withdrawal of the British military and naval forces from Cork and district. It was estimated at a loss of at least one million pounds annually to Cork.

From 1 January 1923 to 23 April 1923 closing down for goods and people traffic due to Civil War damage caused financial loss. The general dockers strike in Cork from August to November 1923 also caused a serious cost to the company. Rates and taxation created a large financial loss for the company, which ultimately led the way to the company’s demise a decade later.

At the AGM for February 1925, the financial losses had expanded. Persistent wet weather ruined the 1924 summer excursion traffic and ordinary traffic was disastrously affected by the depression in trade prevailing all over the South of Ireland. Furthermore, the closing down of Haulbowline and the dearth of work at Passage and Rushbrooke Dockyards, which used to bring the railway so much business, had seriously diminished receipts.

Reference is also made that on 13 August 1924, approval of the Great Southern Preliminary Absorption Scheme 1924 took place. Compensation was given to directors who suffered loss by the abolition of their office. Ultimately though, this took away a more localised focus and created a more centralised focus, whereby several railway companies came under the Great Southern Railway Company.

From 1925 to 1932 the Passage railway limped on with financial deficits. It still carried large crowds during the summer months, but the growing ownership of the motorcar ousted the popularity of travelling on the railway.

Closure of the Line:

On 27 May 1932, it was officially announced that on and from 1 June 1932 all trains on the railway line between Crosshaven and Monkstown in both directions would cease to run. The Cork Examiner notes that the news was met with regret and that the train service between these points was up to some years ago “the main artery of holiday traffic at the popular seaside resort which it linked to the city”. The newspaper relates that within recent years the vast increase in the number of privately owned cars was responsible for a gradual but very noticeable falling off in the passenger service, and the advent of the buses was virtually the death blow to the railway.

In early September 1932, Mr Thomas Jones, chairman of the Passage Urban Council wrote a telegram to the Ministry of Industry addressing the concerns of in regard to the closing of the line. The response in a letter, and published by the Cork Examiner, outlined that the Minister had no power to intervene in the matter. The Minister was informed by the Railway Company, however, that their decision to close the line was reached after mature consideration of the fact that a continuous loss of approximate £4,000 per year in keeping it open; “The Company point out that the public have in a very large measure, deserted the railway services on that line for the more mobile, convenient, and attractive omnibus services, and that it is the intention of the Company to provide full and adequate alternative road services”.

In August 1933, one of the final stages in the abandonment of the Cork, Blackrock and Passage Railway between Cork and Crosshaven was reached when Messrs. Woodward, auctioneers were appointed in charge of the disposal of a number of lots of sleepers and rails from the route.

A Walkway Opens:

The former line re-opened in sections for pedestrians and cyclists from 1984 onwards. Its existence through has not been without controversy in the past and within the present day.

Pressure through aims from historic Cork city development plans through the 1970s to the 1990s still reign to reboot a light rail line from Cork’s South Docks to Passage West.

Strong political and public pressure have staved off such aspirations of a rail reboot function in the past decade in favour of Cork City Council developing a widened greenway, significantly improving its access ramps, and planting over 2,000 native species along the former rail route. The old line has gone from strength to strength in its number usage – its promotion of public health, walking and cycling, connecting the river and the estuary and its strong sense of place makes for an exciting public space.

A conservation programme was also in play restoring the old stonework of the old Blackrock Station and replacing a long gone cast iron bridge. Currently there is also ongoing work on how to bring the greenway from Rochestown to connect up with the Cork County Council section of the railway, which brings the line into the heart of Passage West.

The line over the years has been the subject of local history newspaper articles and a number of books, and a fantastic Facebook page, which promotes its cultural heritage and value in the south east of Cork City.

Read about Joe McHugh Park and Estuary Walk here, 10. Joe McHugh Park and Estuary Walk | Cllr. Kieran McCarthy