Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 6 August 2015

Cork Harbour Memories (Part 30)

Colonising a Swamp

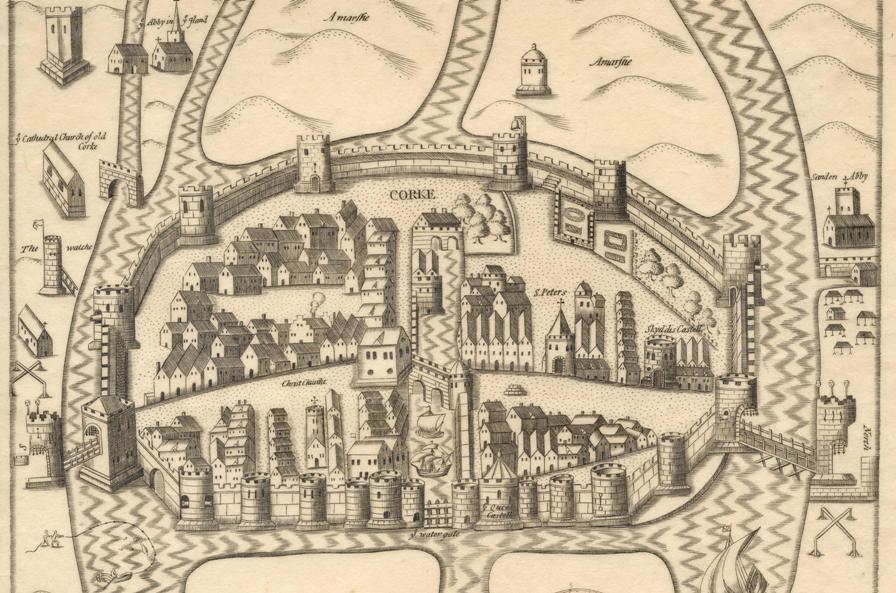

President of the Munster Plantation George Carew’s Map of Cork circa 1600 shows the town wall of Cork encompassing an oval shaped settlement on a swamp. His emphasis is on showing off the infrastructure. He depicts the town as a spacious, strong and prominent settlement, complete with the protection of drawbridges and the eastern portcullis gate called Watergate. The mechanics of raising up of such structures must have got damp and noisy, must have creaked, and must have irked the visitors to the town. Maybe many of the citizens didn’t hear those sounds, being so used to them. The town was there for several centuries. Access was through these points and people were used to their everyday function in giving and refusing access to the town.

The walled defences, 1,500 metres in circumference, were to provide security for its inhabitants up to 1690. They also controlled light and shade, the wall overlooked and in a sense organised the lives of citizens. On the map, the buttress walls and its drawn lines that rise from the marshy ground give the structure a striking strength and depth of foundation, physically, spatially and culturally. The hardness and indestructibility of the stone has a noble look to it and fitted Carew’s idea and vision of a colonised landscape. Much of the town wall survives beneath the modern street surface and in some places has been incorporated into existing buildings. Carew presents a wall on his map almost mass concrete looking – as in he doesn’t show the reality of the use of multiple stones in its construction– as seen in the wall on display in Bishop Lucey Park. The wall comprised two stone types, limestone and sandstone,. The engineering involved in its construction was substantial. The citizens must have had problems in laying foundations into the swamp. Their timber scaffolding must have collapsed at times. The courses of the stone must have collapsed. It was a jig-saw puzzle in its construction.

In a present day context, echoes of the ground plan of the walled town survive. If one starts on the corner of the Grand Parade and the South Mall, on the city library side, the walls of the medieval town would have extended the full length of the Grand Parade, along Cornmarket Street, onto the Coal Quay, up Kyrl’s Quay to the North Gate Bridge. From here they would have extended up Batchelor’s Quay as far as Grattan Street, then turning southwards, the walls would have followed the full length of present day Grattan Street as far as present day Clarke’s Bridge. The walls then followed the course of the River Lee back to the starting point.

Some of the wealthier merchants formed the corporation and lived in tower houses or large two to three storey castle-like structures. They were as important as the infrastructure and many were the key agents of governance for centuries. These families included the Roches, Skiddys, Galways, Coppingers, Meades, Goulds, Tirrys, Sarfields, and the Morroghs. Their names were all involved in the running of the town from its inception in the late 1100s to the seventeenth century. They also controlled large portions of Cork’s trade and rented out numerous plots of land to other citizens – Irish natives and English colonialists. Carew’s depiction shows two tower houses within the precincts of the medieval core, Skiddy’s Castle and Roche’s Castle. Skiddy’s Castle was located in the north east sector of the town over-looking North Main Street, close to North Gate Drawbridge while Roches Castle was located at the eastern end of middle bridge, the structure that connected the enclosed medieval islands together.

Carew also places emphasis on other public buildings in this walled town. The corporation of the town conducted public business in the south west quadrant of the walled town or to the west of South Main Street. The council tower, armoury, the town’s court house, the commandant’s house and the treasury were all in this location. In the south west quadrant of the town, the town post office was located, evidenced from present day Post Office Lane situated today adjacent to the Grand Parade. In addition, Christ Church existed in this section, which was rebuilt in 1720. The merchant’s hall was also present in this area and at the western end of Middle Bridge on the southern island side was the location of the custom house or Exchange. All ships docking at the quay inside the town had to report their goods to this building. In the north west section of the town or to the west of North Main Street, a garrison was located for soldiers just south of Skiddy’s Castle. The governor’s house was situated in this area along with St. Peter’s Church, which has taken the form of the Cork Vision Centre. The other main feature in the north west section was the market square from which the town crier shouted and communicated to the population of the town. Carew only depicts two citizens in a boat fishing near South Gate Bridge. But for every house shown in the town, families lived their lives and made the walled town of Cork their home.

To be continued….

Captions:

804a. Section Map of Cork, late sixteenth century as depicted in Sir George Carew’s Pacata Hibernia, or History of The Wars in Ireland (1633), vol. 2, opp page 137.

804b. One of the recent Medieval re-enactment days in Bishop Lucey Park (picture: Kieran McCarthy)