Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 1 October 2015

Cork Harbour Memories (Part 31)

The Construction of Elizabeth Fort

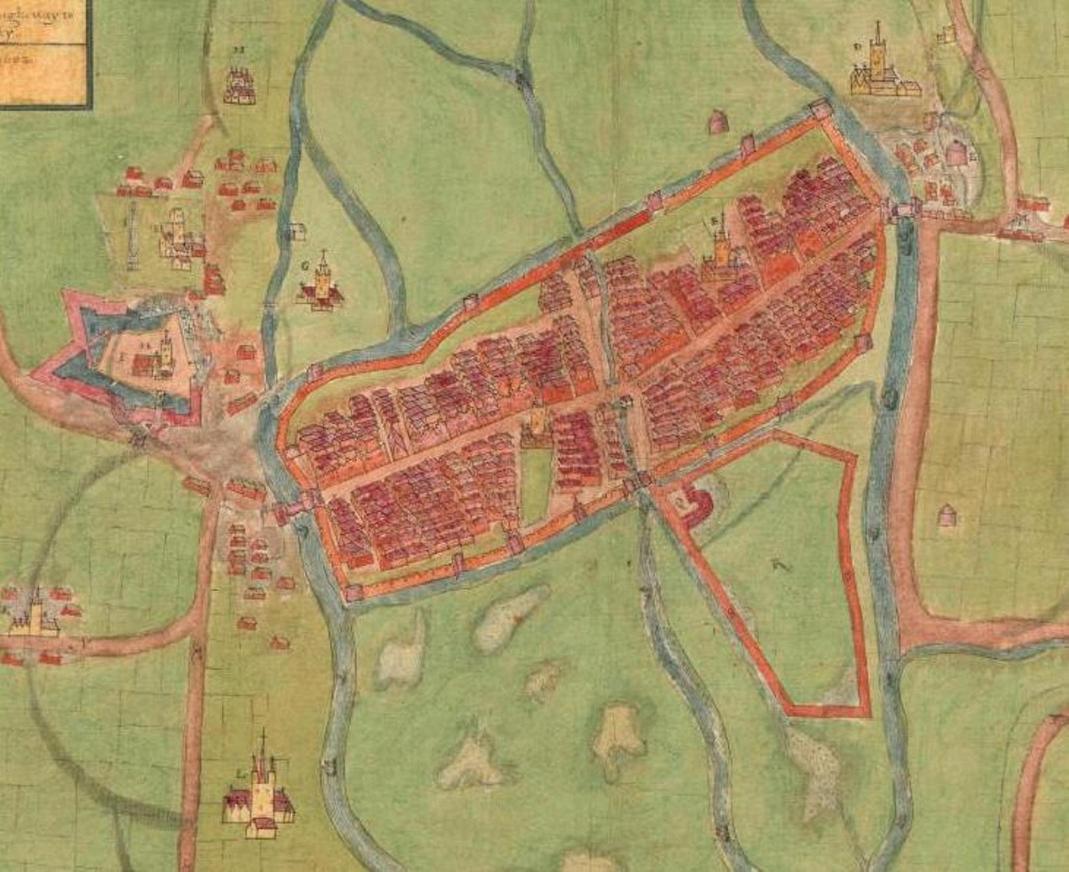

Continuing on to explore the old maps of the City, the colourful Plan of Cork c.1600 based in the Hardiman Collection in Trinity College Dublin places an emphasis on an ordered walled town on a swamp complete with houses, laneways, drawbridges. Commissioned by George Carew, President of Munster or the plantations within the south of the country, this is the second of two known maps of the walled town by him. In this plan the emphasis is less on the height of the walls and more on the roads leading into the settlement. It shows a new dock area to the east to accommodate increased trade. But it is the showcasing of Elizabeth Fort on the left (with the Holy Rood Church within), which is perhaps why this map might of been created.

Due to the stand-off in the Battle of Kinsale between English and Irish and Spanish, a reference in State Papers from late 1601 details Carew paid 200 labourers to expand an extensive trench in the southern suburbs, and that the project was paid by the walled town and the English administration in Ireland. A further reference in the State Papers from Carew to Lord Mountjoy on 6 August 1602 reveals Carew’s interest in creating the large earthwork; “That irregular work your Lordship saw at the south end of Corke, first intended for no other end than a poor entrenchment, for a retreat, is now raised to a great height equal or above all the grounds about it, and so reinforced with a strong rampart, as a powerful enemy shall not carry it in haste, and whilst that work holds out it shall be impossible for an enemy to lodge near that end of the town. The work is great, the Queens charge in erecting it nothing”. References in the same papers also mention the construction of a new fort at Kinsale (in time to become James Fort) and a fort on Haulbowline Island in Cork harbour.

In April 1603, Queen Elizabeth I died and a new protestant king James I was proclaimed. The Council Books of the Corporation of Cork relate that in the case of Cork, a Captain Morgan was given the responsibility by the lord lieutenant of Ireland, Deputy Mountjoy to relate the news. In Cork, the message was received by a George Thornton, one of the Kings’ appointed commissioners for Munster who gave the news to the mayor of Cork, Thomas Sarsfield. In those days, due to previous charters, the mayor and the citizens of any royal town had the choice of refusing to proclaim a new monarch on the English throne but it rarely occurred due to the threat of military force. However, in this case, the mayor, Sarsfield was anti the crown and in favour of the rebellious Irish living in the area. He knew that he could not outright refuse but decided to use niches in the political system to delay the process of proclamation.

Sarsfield took his right to call together elected officials of the Corporation at the city court house to decide on the matter. During this time, he was informed that the rest of the large walled towns had proclaimed James and kept Thornton, the English commissioner who was waiting for a response outside the meeting. Sarsfield managed to delay the process further by declaring that the meeting had to be adjourned until the following day. Under the pressure of time, Sarsfield and the citizens contemplated attacking a fort at Haulbowline but agreed on arming themselves and preventing any English forces from entering the town.

This rebellion did not deter Thornton from carrying out and at this stage enforcing the proclamation that James I was the new king. Thornton and eight hundred soldiers proclaimed the new king in the north suburbs of the city around Shandon Castle. A number of principal characters are recorded in this revolt. One such man, a Thomas Fagan had an interesting personality. One incident involving Thomas included the time he fired a cannon at an Englishman, a James Grant. He had previously attacked Grant and stripped him of his clothes. Fagan was also responsible for breaking into the city’s ammunition store within a former tower house called Skiddy’s Castle. This store was located at the northern end of North Main Street, now the site of the National Rehabilitation Board. However, firing cannons at people, raiding gunpowder stores were only one part of his personality. Fagan also carried a white rod around the city and declared himself the principal church-warden in the city. It is recorded that any English person or protestant that passed him was mocked without fail.

Even, certain Englishmen took the side of the rebels. John Nicholas, brewer and a John Clarke, tanner mounted a small portable cannon on top of the walls and fired at two soldiers, killing them. The town’s recorder, John Mead was also on the side of the rebellion and used his political clout accordingly to support the rebels. Mead ordered the king’s store keeper, an Allen Apsely at Skiddy’s Castle to be killed and his arms to be taken away. He also ordered the arrest of the clerk of the munitions, a Michael Hughes along with his wife who were sentenced to be thrown over the walls as a means of execution.

To be continued…

Captions:

812a. A description of the Cittie of Cork/ Plan of Cork, circa 1602 by George Carew (source: Hardiman Atlas, Library of Trinity College Dublin)

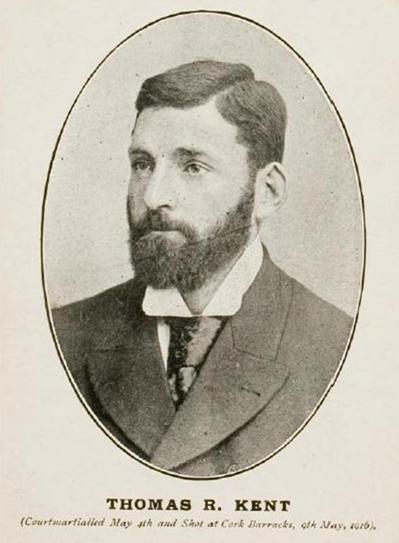

812b. Elizabeth Fort from A description of the Cittie of Cork/ Plan of Cork, circa 1602 by George Carew (source: Hardiman Atlas, Library of Trinity College Dublin)