Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article, 5 February 2015

Cork Harbour Memories (Part 9) –Links to an Enchanting Port

Through Bordeaux and being on the edge of outposts of Anglo-Norman Rule, new links for Cork were created with the Iberian Peninsula. In 1360, new trade routes were established with Spanish and Portuguese ports, especially with Lisbon and Oporto. Both countries possessed a large demand for cloth. This demand was met and in return olive oil was imported. One can imagine Cork dockers or quay workers taking jars of olive oil off ships speaking to sailors about their journey from the warmer climes of the Mediterranean to the storm ridden North Atlantic.

It has always been a question for me what was the impact of foreign trade from other destinations on Cork. These destinations had their own cultural histories. How were the traditions and customs of exporting and importing cities such as Cork affected? What were the effects of all these connections? How did the financiers of ships, sailors, dock workers perceive maritime trade, apart from the profit of it? Were their aspects of Lisbon’s essence for example, its urbanity, its ideas of civilisation, its connection to the sea, and its maritime culture that Cork sought to emulate?

A look at the Lonely Planet guide to Lisbon reveals it as one of the oldest cities in Europe with multiple phases of development. It has always had an international stage presence of sorts. It is steeped in legend. It is a city founded and named by Ulysses as Ulissipo or Olissopo, which has its genesis in the Phoenician words “Allis Ubbo”, meaning “enchanting port”. It is from there, according to legend, that Lisbon got its name. The city’s prominent position on the Tagus estuary inextricably bound its character with the sea.

Its early history reveals a place that was sought after as a trophy city – those who control it have access to the Atlantic and the Mediterranean. It was a battlefield for Phoenicians, Greeks and Carthaginians. However it was the Romans who started their two-century reign in Lisbon in 205 BC. During the Roman period, Lisbon became one of the most significant cities in Iberian Peninsula and was renamed Felicitas Julia. In 714, the Moors arrived to peninsula and resisted against Christian attacks for 400 years. When the Christians finally recaptured the city, it took one more century to repel all the Moors from the peninsula. Lisbon became a place about the marrying of religion and commerce.

Lisbon emerged as a nation state in the early twelfth century, recognition of its government and citizens’ belief and confidence in its vision for its future. It was dependent on commerce and was established on far-flung maritime empire into the eastern Mediterranean. It considered the sea as highly important and itself open to foreigners and outsiders – Lisbon was the world’s most prosperous trading centre; hence perhaps the settled Anglo-Norman communities of Britain, Ireland and France took the opportunity to try to tie in with Lisbon’s maritime profit and perhaps the vision of a city of the sea. In 1142 there had been a failed attempt to conquer Lisbon by a combined host of Anglo-Norman and Portuguese crusaders within the wider context of both the crusader movement to the Holy Land and the reconquest of Iberia.

The importance of the sea to Lisbon was marked in the growth of naval activities and military installations. Confidence in itself led to faster and larger ships that could be provision laiden to meet long voyages. Small single-mast boats were gradually replaced by more sophisticated, larger vessels of three masts. The Portuguese pulled up their anchors to seek new lands, opportunities and colony and empire building. Eventually the caravel ship, swift and much admired abroad, enabled exploration of the far-off West African coast. The fifteenth century became, an era during which Portugal enjoyed abundant wealth and prosperity through its newly discovered off shore colonies in Atlantic islands, the shores of Africa, the Americas and Asia. Vasco da Gama’s famous discovery of the sea route to India marked this century. It also inspired also fund expeditions. Columbus led his three ships – the Nina, the Pinta and the Santa Maria – out of the Spanish port of Palos on 3 August 1492. His objective was to sail west until he reached Asia (the Indies) where he perceived riches of gold, pearls and spices awaited.

Long distance fishing and the preservation of fish by salting became part of Lisbon life. Portuguese merchant shipping was established all over Europe. Lisbon became a bustling sea port with 400 or 500 ships using the facilities of the harbour. The city lay strategically placed between Europe and Africa, and eventually between Europe and America. Among the cargoes carried out of the port were those of cork, olive oil, wine, hides, wax and honey.

Cork I have no doubt profited financially and culturally from Lisbon and from its further afield connections. Indirectly Cork like many other maritime settlements in Western Europe took inspiration in aspiring to be a city of the sea, one steeped in legend, to be a trophy settlement to be fought over, one abounding in belief and confidence and willing to seek out new opportunities. Indeed, the age of the explorations was to further open Cork’s links with the wider world.

To be continued…

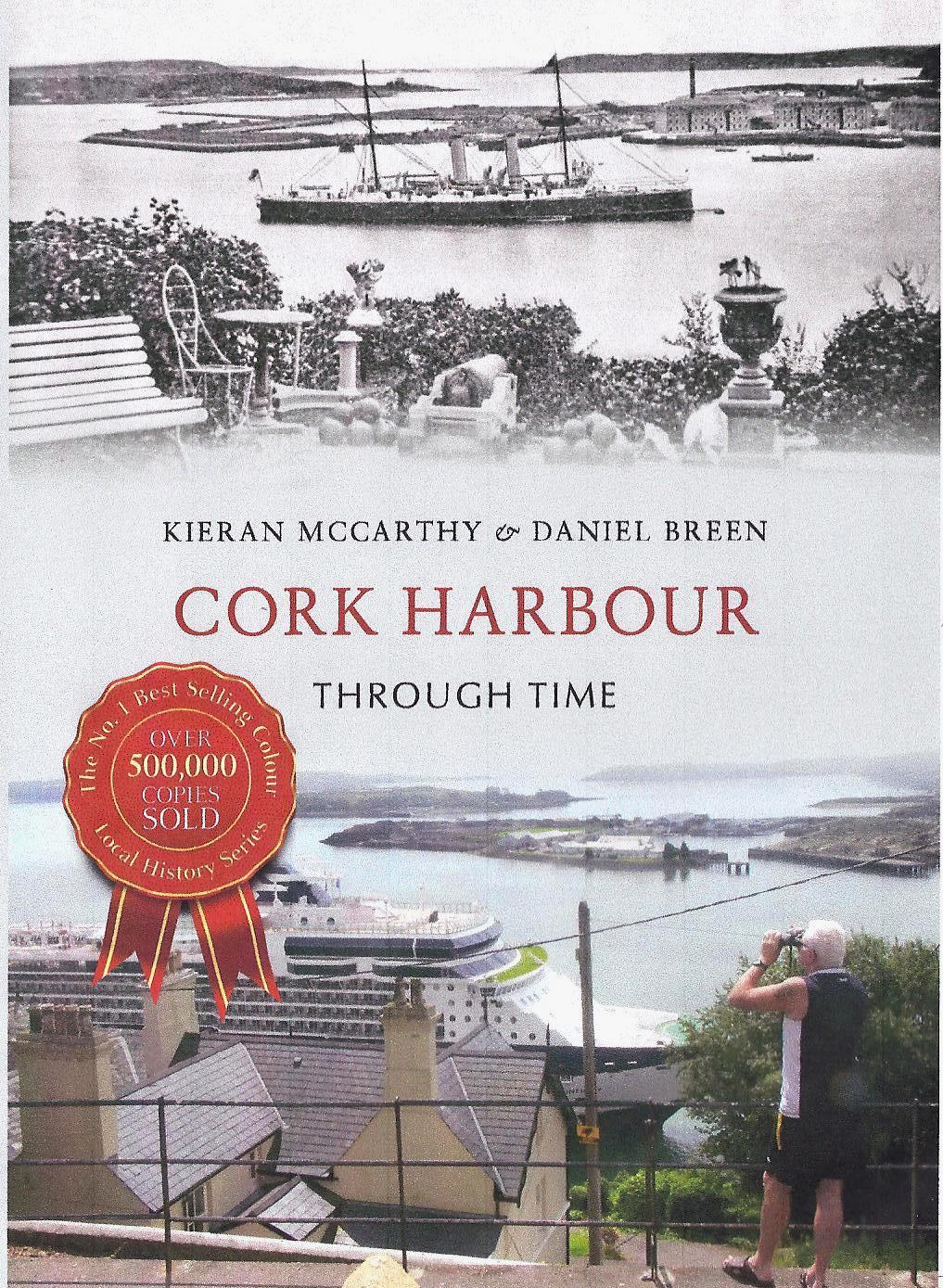

Caption:

778a. The Discoveries Monument, Lisbon; it represents a three-sailed ship ready to depart, with sculptures of important historical figures such as King Manuel I carrying an armillary sphere, poet Camões holding verses from The Lusiads, Vasco da Gama, Magellan, Cabral, and several other notable Portuguese explorers, crusaders and monks (source: Cork City Library & Jack Macolm, Lisbon, City on the Sea).