Article 774 –8 January 2015

Cork Harbour Memories (Part 5) –Tales of Two Cities

With the Irish Channel being a type of maritime motorway in its day, the connection between Cork and Bristol was close during the early thirteenth century. I think sometimes, we view the historic development of Irish cities as self contained but settlements such as Cork have always drawn on ideas of place making put forward elsewhere in western Europe.

Continuing on from just before Christmas, in the early 1200s, the number of religious and charitable establishments in Bristol and Cork grew rapidly. From the earliest times of the Anglo-Norman conquest of England and of Ireland, they were interested in exercising control over the Church (for use in assimilation purposes and for its land). General history books in Bristol library such as Peter Aughton’s book, Bristol, A People’s History (2003), detail that a Dominican Priory was established in 1227-9 while a Franciscan Priory in 1234. Both were founded to the influence of Anglo-Norman family of Berkely who possessed territory near St. Mary’s Church, Redcliffe. Other church associated institutions established at the time included St Mark’s Hospital, St Bartholomew, St Lawrence, St John’s Hospital for sick poor, St Catherines, St Mary Magdalene for lepers And Brighbow for male lepers located outside the town’s eastern boundaries.

In 1250s, the order of Augustinians was founded near Temple Gate while in 1267 a Carmelite Friary was founded. In Cork, a Dominican and Franciscan Friary were both established in 1229 while an Augustinian abbey was founded much later between the years 1275 and 1285. The Cork establishments still have very elaborate and beautiful churches in our city.

In Bristol, the early 1200s marked conflict between the Berkelys of Redcliffe and the civic administrators over accessibility to the town. The Berkelys felt that they were discriminated against. Consequently in 1239, a new bridge was built which connected Redcliffe to the walled settlement. By 1247, the Redcliffe area became part of the town when it was walled in. In addition, a new harbour was dug at the junction of the River Froom and the larger River Avon. Between 1275 and 1300, Bristol’s seal or Coat of Arms was created, Bristol castle with a ship seeking refuge under its gates and walls and a sailor. My own gut is that Cork’s coat of arms is linked to Bristol’s one. I cannot prove it with historical detail but the close links and similar culture of development between the two cities do point to it.

The late thirteenth century coincided with Cork expanding rapidly as a municipal centre. In 1273, the first Mayor named Richard Wine was appointed. This was a sign that Cork was taking its place amongst other up and coming English settlements. As a city we are also lucky that historical developments of the thirteenth century have survived the test of time. Concerning trade links, the oldest and richest in historic research and detail is the insightful Economic History of Cork by William O’Sullivan (1937). The historical evidence describes that the port at Cork was a wealthy earner. The customs returns of Irish ports in the period 1276 to 1333 show that Cork was the third most important port in Ireland, after New Ross and Waterford and that it was estimated that Cork possessed 17 % of total Irish trade. In addition, it is recorded that the main export duties were paid on wool, wool-fells and hides. These figures highlight Cork’s growth as a premier North Atlantic port.

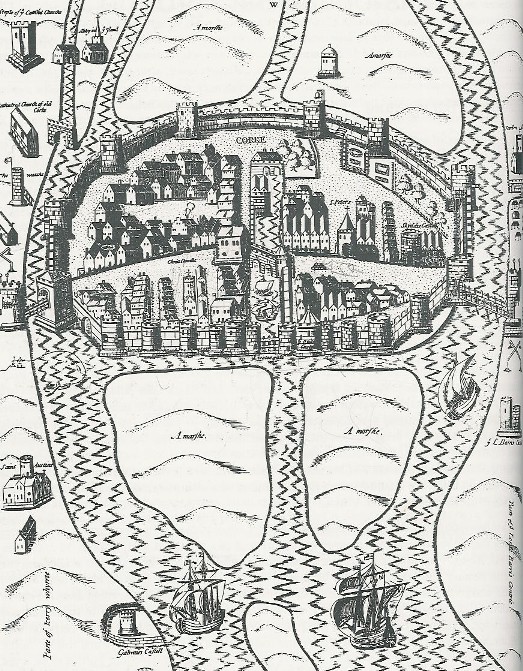

In 1284, the townscape of Cork’s walled settlement was critiqued by King Edward I. He authorised the collection of additional murage tolls or taxes on the land so that walls of the southern island i.e. around South Main Street area could be improved. He described the bridges of the town to be ruinous and the port as being so deteriorated that a swift response was needed to revamp it. The monarch also detailed that there was a vacant place, Dungarvan or the northern island, which should be built on and that it would be of great advantage to the citizens of the town. In time this area was built upon and North Main Street emerged.

In 1317, paving and the repairing of facets of Bristol’s walled town began. In the same year in Cork it was decided to enclose with stone walls, the southern and the northern island (Dungarvan) of Cork. Hence a 16 acre settlement site across two marshy islands was created. Access into this town was via three entrances – two drawbridges and an eastern portcullis gate which lifted up and down on water. A channel of water was left between both islands; the western half was dominated by a millrace, the eastern half by an interior dock within the walled town.

As the thirteenth century progressed, commercial leaders in Bristol and Cork began to hold chief places in civic government. For example John de Bristol became Mayor of Cork in 1336. After the extension of the wall circa 1300, several taxes are listed in subsequent royal charters granted to the city which refer to numerous traded articles. In the thirteenth century, Bristol was to open up trade with France in the form of the Gascony wine trade. Subsequently links between Ireland and other French ports through Bristol’s contact grew steadily.

To be continued…

Happy New Year to all readers of this column

Caption:

774a. Pacata Hibernia view of the walled town of Cork, c.1575 (source: Cork City Library)