Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 9 April 2015

Cork Harbour Memories (Part 18)

Stories in Stone

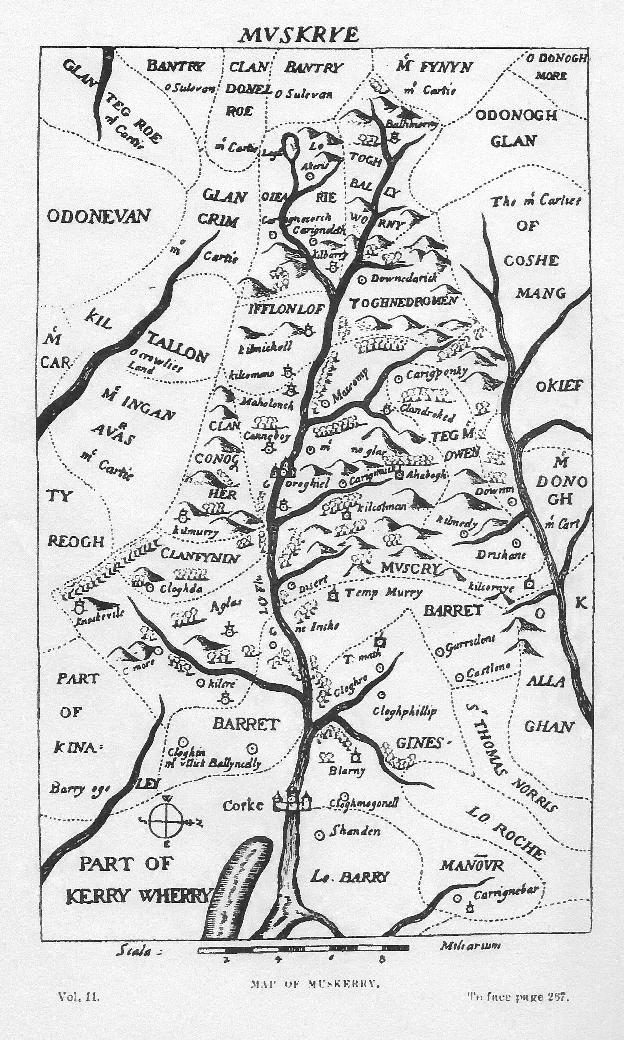

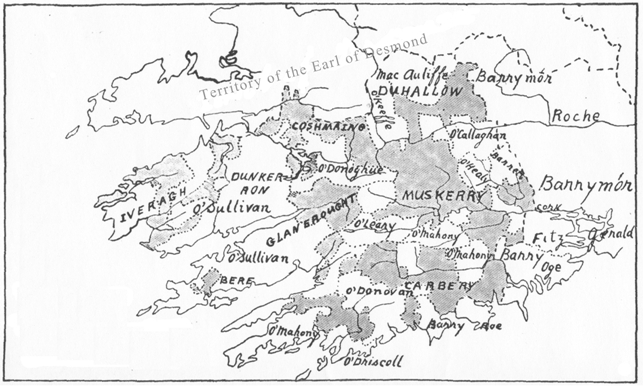

Staying with George Carew’s map of sixteenth century Muskerry (see last week), one of its concerns was the showing of castles and churches – his castles are marked with a circle and a dot whilst his churches are demarcated with a snowman type delineation. The dashed lines reflect fluctuating territorial lines between Gaelic families and Carew’s long list of allies and adversaries. The map also points to small woodland areas across the territory. Carew’s circled dots very much under represent the prominence of castles in the landscape. The majority were tall slender stone tower houses with an estate surrounding them. Many still stand as ruins, haunted in a sense by the human life that once drove survival and civilised structures in them. All are worthy of remark and all have been written about through the ages.

The tower house at Kilcrea was built by Cormac MacCarthy in the mid fifteenth century and lies only a few miles from Cork City. In its heyday it provided a buffer area like Blarney Castle – that those who travelled west along the River Lee, knew they were entering retaken Gaelic territory. The name Kilcrea (Cill Chre) harks back to an earlier history and means the Cell of Cere, Cera or Cyra. St Cere, who lived in the sixth century. She is is said to have founded a nunnery about a mile east of the friary in the parish of St Owen’s, now called Ovens. It appears that Kilcrea was a location with ecclesiastical associations long before Cormac Láidir MacCarthy founded the Franciscan Friary there circa 1465 AD. The friary was dedicated to St Brigid of Kildare.

A few fields west of the Franciscan Friary stands the impressive ruined tower house of Kilcrea. It was built by Cormac McCarthy, Lord of Muskerry and was situated nearly in the centre of the valley, within a short distance of the Bride. Although inferior in importance and size, to that of Blarney, it was and still is a considerable structure to walk around and explore in safety. John Windele, antiquarian, in his Historical and descriptive notices of the city of Cork and its vicinity (1839) eloquently describes the castle of Kilcrea as standing in isolation; ”the warrior pile, stands in stern loneliness, denuded of its circling woods, isolated and ruinous – a better taste may again restore to it some of its sylvan honours”.

This abandoned “warrior pile” of blocks of limestone is like a complex jigsaw puzzle of stone and is well put together. This was a building made to last, made to be permanent. The stones are heavy – their weight now intertwining with the weight of history which now governs them. The quoin or corner stones and the material remains of mortar are testament to the masons who planned and put this prominent structure together. Its site is enclosed by a narrow moat still filled with water. The castle has a small fortified area at the eastern side of it, and is defended by curtain walls, and two square vaulted towers, now in ruins.

Inside the keep, it is divided by two semi-circular stone arches (being turned on a kind of basket work of interwoven sallows, or willow wattles). One arch is above the other, at the heights of one third, and two thirds of the building. All of the intermediate floors have been destroyed. Stone corbels for timber floors remain to entice the visitor to think about creaking floor boards. The basement rooms like those at Blarney are merely lit by narrow loops. At the south side of the vestibule is a stair case, which consists of an easy flight of seventy-seven steps and runs up the entire height of the building, becoming spiral as it approaches the higher chambers. A number of small closets are attached to the upper rooms, all of which are vaulted.

The upper chamber formed the main hall – a room of state and was at one time spacious and well lit. Its floor is now overgrown with grass. It was lit by three spacious windows, with stone mullons, and ogee headed tracery of a basic design – but enough to entice you to rub your hand over this ancient piece of art work. John Windele after his visit remarked that at the north side of the main hall chamber, was formerly a “capacious fire place with a well-executed mantle-piece, on the impost of which was an inscription, in raised letters commemorating rather modern repairs”. This was also removed some years before Windele’s visit and during my visit the missing fire-place was also quite apparent. From the ruined battlements is obtained an extensive view over the valley to the west, embracing the view of Castlemore and Cloghdha Castle near Crookstown.

On my visit the hum of a nearby lawnmower seemed to bounce from wall to wall in the interior, making me look behind you at every corner. The structure is haunted by its stories and history. This haunting feeling is also one, which Windele also picked up upon; “it has been haunted by a phooka, or mischievous spirit, under the form of a black crow; so that nightly visitors would require strong nerves to brave the terrors of its lonely and forsaken chambers”.

To be continued…

Captions:

787a. Kilcrea tower house, March 2015 (picture: Kieran McCarthy)

787b. Interior of Kilcrea tower house, March 2015 (picture: Kieran McCarthy)

787c. Entrance arch and stairs, Kilcrea tower house, March 2015 (picture: Kieran McCarthy)