Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 2 April 2015

Cork Harbour Memories (Part 17)

Carew’s Campaigns

George Carew’s impact on the cultural and political landscape of Munster was vast. By the spring of 1586 Carew had been knighted and was sent on a private mission by Elizabeth I to Ireland. Carew arrived into a country where huge tracts of the Earl of Desmond’s lands in Munster had taken over by the English crown. About 300,000 acres of land were confiscated in total. From 1585, the plantation of Munster had began and new English settlers were given land. As a reward to Carew’s loyalty, he acquired large estates.

Carew’s rise in political circles and in English power structures in Ireland was quick. In February 1588 Carew was appointed Master of the Ordnance, and returned to Ireland. In 1590 he was admitted to the Privy Council. Two years later in 1592 he was made Lieutenant-General of the English Ordnance, and in 1596 and 1597 he was engaged with Essex and Raleigh in expeditions against Spain. In March 1599 he was appointed to attend the Earl of Essex to Ireland and on 27 January 1600 he was made President of Munster.

Carew’s proceedings for the next three years during his term as President are carefully detailed in Pacata Hibernia (1633), nominally written by Thomas Stafford, but inspired by himself. The Battle of Kinsale features prominently in his pages on campaigns in Cork. On 23 September, 1601, a Spanish fleet entered the harbour of Kinsale with 3,400 troops in forty-four vessels under the command of Don Juan del Aguila. They immediately took possession of the walled town. Del Aguila despatched a message to Ulster to O’Neill and O’Donnell to come south without delay. Lord Mountjoy and Carew mustered their forces, and at the end of three weeks encamped on the north side of Kinsale with an army of 12,000 men.

O’Neill arrived on 21 December 1601 with an army of about 4,000, and encamped at Belgooly north of Kinsale, about three miles from the English lines. His advice was, not to attack the English, but to let their army suffer from the cold. Already 6,000 of them had perished. But he was overruled in a council of war, and a combined attack of Irish and Spaniards was arranged for the night of 3 January, 1602. Efforts to rally his ranks were in vain. Del Aguila’s attack did not come off and the Irish lost the battle of Kinsale. Soon after the battle Del Aguila surrendered the town. He agreed also to give up the castles of Baltimore, Castlehaven, and Dunboy, which were garrisoned by Spaniards. Shortly afterwards, he returned to Spain.

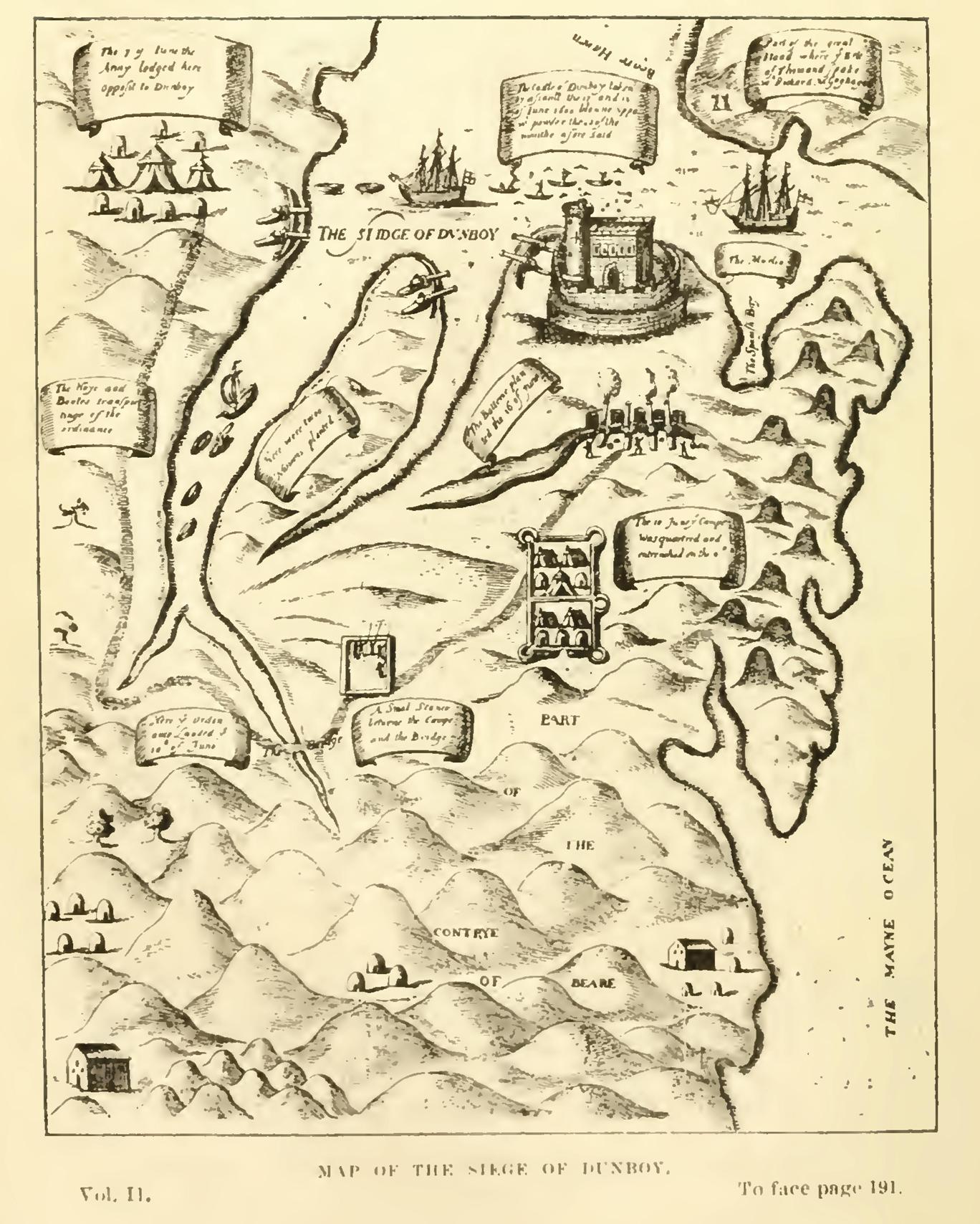

The Dunboy Castle though was not given up without a fight. In April 1602 Carew took Dunboy Castle and estate, which was the stronghold of the O’Sullivan Bere clan and built to guard the harbour of Berehaven. The O’Sullivan Beres controlled the fishing fleets off the Irish coast and became rich through the collection of taxes on the rights of passage. Dunboy was surrendered to the Spaniards, on their invasion of Ireland in 1601 by its owner, Daniel O’Sullivan. Early the following year following the treaty at Kinsale the Irish clan took possession of the castle by surprise and seized the arms and ammunition the Spaniards had deposited there. Sir George Carew as well as 5000 soldiers were sent to suppress the O’Sullivan Bere. In April, the English army marched against the O’Sullivans to Bantry, and on 6 June set up camp on the opposite side of the castle’s bay.

Dunboy Castle was considered impregnable and was only defended by 143 men under the command of Richard McGeoghegan. It took two weeks to take it during which it was almost destroyed by artillery fire. After hand to hand fighting the remaining 58 survivors were executed in the town square. The entire castle site lay in ruins until 1730 when the Puxley family were granted the Dunboy Estate along as well as other land belonging to the O’Sullivan’s. They then set about building a mansion close to the Puxley Castle keep and Dunboy Castle was left in ruins. Very little now remains of the old castle. It now comprises of just a few collections of stones which in parts are almost completely covered with overgrowth.

The end of the Cork wars found the country in a deplorable condition of ruin and depopulation. Carew and the other English leaders, and their Irish allies, profited largely by the confiscations that ensued. Carew returned to England in March 1602 at the earnest request of his friend Cecil. Carew stood in as high favour with King James I as with Elizabeth, and in the Irish Patent Rolls are recorded the numerous grants bestowed on him from time to time. In 1605 he was created Baron Carew, and was made Governor of Guernsey. In 1611 he was again despatched to Ireland as head of the commission for the plantation of Ulster.

The favour which followed him through the reigns of Elizabeth and James continued unabated under Charles I, by whom he was created Earl of Totnes. Much of his later years were spent in arranging his invaluable collection of papers connected with the history of Ireland. Carew died at the Savoy, London, 27 March 1629, aged about 72, and was buried at Stratford-upon-Avon. He left one daughter. His Countess survived him many years.

To be continued…

Captions:

786a. Map of Siege of Dunboy, late sixteenth century as depicted in Sir George Carew’s Pacata Hibernia, or History of The Wars in Ireland (1633), vol. 2, opp page 191.

786b. Ruins of Dunboy Castle, present day (picture: Kieran McCarthy)