Public talk with Kieran, Cork Harbour Through Time – explore the old postcards of one hundred years ago, histories and memories of Cork Harbour, with Passage Historical Group, Wednesday 21 October 2015, 8pm; all welcome.

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 15 October 2015

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 15 October 2015

Cork Harbour Memories (Part 33)

A Busy Seventeenth Century Settlement

Cork in the first decades of the seventeenth century was valued as the third most important port after Dublin and Waterford. The growth in prosperity was mainly attributed to the increase in utilization of the surrounding pastoral hinterland surrounding the city. Large sections of woods were cleared in Munster to accommodate the large demand for pasturalism. However, in 1610, a report by the commission of the Munster Plantation noted that the woods were being depleted too fast in order to clear land so sheep could graze on it.

In the early 1600s, it is recorded that the main areas that Cork was importing from and exporting to included Seville in Spain, Lisbon in Portugal, St Malo and the Saintonge area in the south-west of France, cities in the north of Italy such as Pisa, western English port cities such as Bristol, Cologne and the Rhine area in Germany and towns such as Delft in northern Holland. New trading connections were also established with the Canary Islands and Jersey. The main imports from the first four countries in the above list mainly consisted of wine while from the others iron and salt were the principal imports. This is also reflected in the archaeological evidence from sites with preserved late medieval contexts. A large percentage of the pottery discovered dating to the seventeenth century was from the warm temperate countries where wine was grown.

Hides, tallow, pipestaves, rugs and friezes were the main exports along with cattle, wool and some butter. There was an increasing trade in beef, which led to the moving of slaughter houses or shambles outside the city walls. Indeed, such was the extent of active trade in Cork whether it be exporting or importing, that there was increased activity in the pirate activities. It eventually reached the stage where special convoys were introduced to protect merchant ships especially around the south coast.

The physical nature of the walled city appears constantly in Cork Corporation priority list regarding revamps. The old Corporation records detail the worsening condition of the town walls. In January 1609, a plan to build a new court house on the site of King’s Castle, which was the northern control tower of the central Watergate into the town, was delayed. The walls onto which the courthouse were be attached were crumbling and in danger of collapsing. New walls would have to be built, so the new courthouse could be built.

The poor condition of the town walls continued to be a major issue for the Corporation into the decades of the 1610s and 1620s and even the bridges leading into the town were described as ruinous and calls were made for them to be mended. From 1614 on, all monies earned by the Corporation from taxing imports such as wine were to be spent the repairing of the walls. However, by 1620, it was agreed that the incoming revenue into the settlement’s coffers was not enough and a bye-law was passed where several municipal rates were to be brought in as well as increasing of existing rates. Taxes were raised on several regularly exported commodities such as animal feed such as oats, animal skins such as horse, deer, fox and on drinks such as beer and wine. However, the taxes regarding docking your boat, passage through the city, tax on the land you owned were abolished.

In 1620, an English traveller described Cork as “ a populous town and well compact, nothing to commend it…the town stands in a very bog and is unhealthy”. The physical state of the town also became an issue in May 1622 when lightning struck one of the thatched roofs in the eastern part of the city which caused a large scale fire to rapidly spread from one thatched roof to the next. According to the historical records, the fire began between eleven and twelve o’ clock in the morning. Indeed, apart from one clap of lightning there was also a second clap of lightning which lit the houses in the western part of the city. It is detailed that the since the houses overlooking the main street were in flames, the people trapped between the two fires were forced to flee into the city’s main churches, Christ church on South Main Street and St. Peter’s on North Main Street. Both of these churches are recorded as being constructed of stone and having a slated roof which saved the lives of numerous townspeople. The people who did not make into the churches were unfortunately consumed by the fire itself. In September 1622, an order was passed that the stone walls be built and the roofs be replaced by slate or timber boards.

The early seventeenth century was an era of unprecedented social upheaval whereby a large part of society consisted of a Catholic majority ruled by a Protestant sovereign. As the seventeenth century progressed, Catholicism became more a political movement than a religious one which aligned itself and made full use the church in Rome as a reason for rebellion.

To be continued…..

Captions:

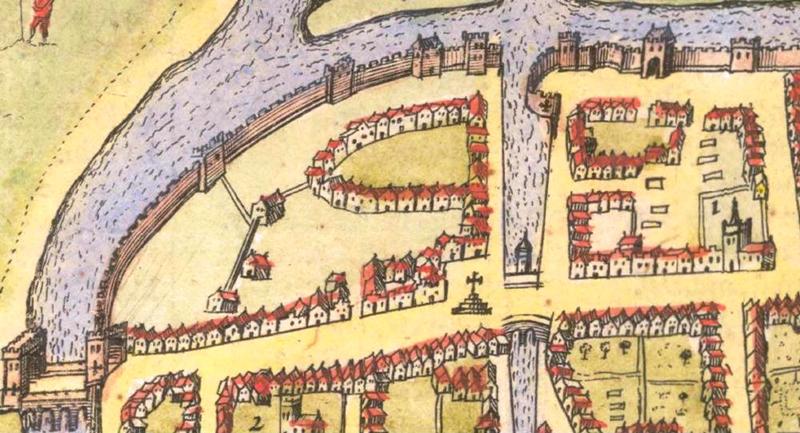

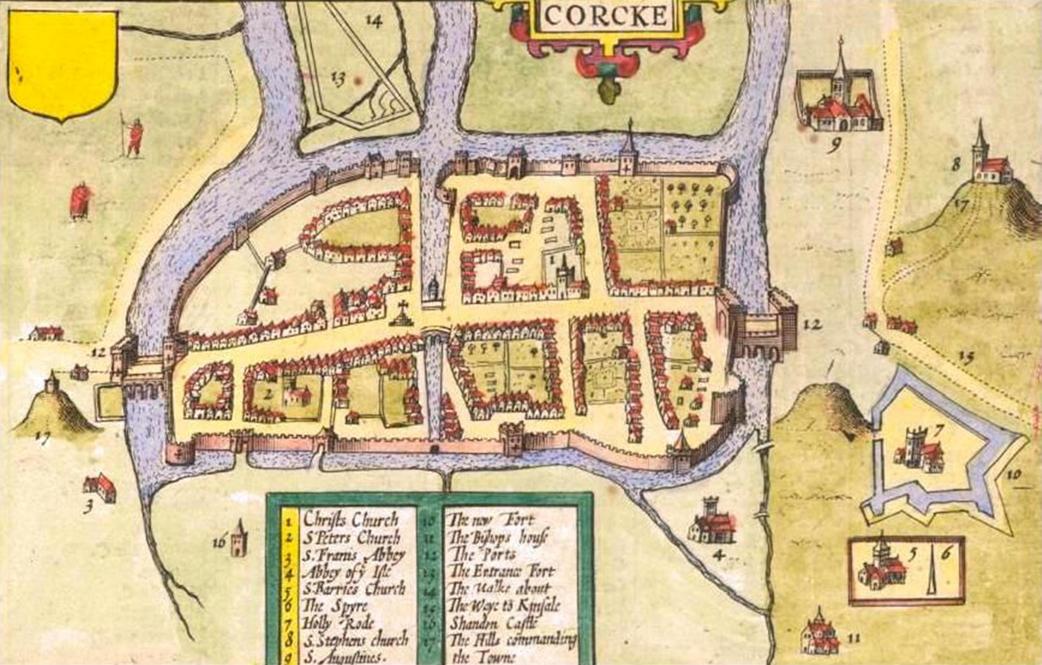

814a. Depiction of Cork’s interior dock, the Watergate complex, from John Speed’s ‘Corke’ from his Province of Munster c.1610-11 (source: Cork City Library)

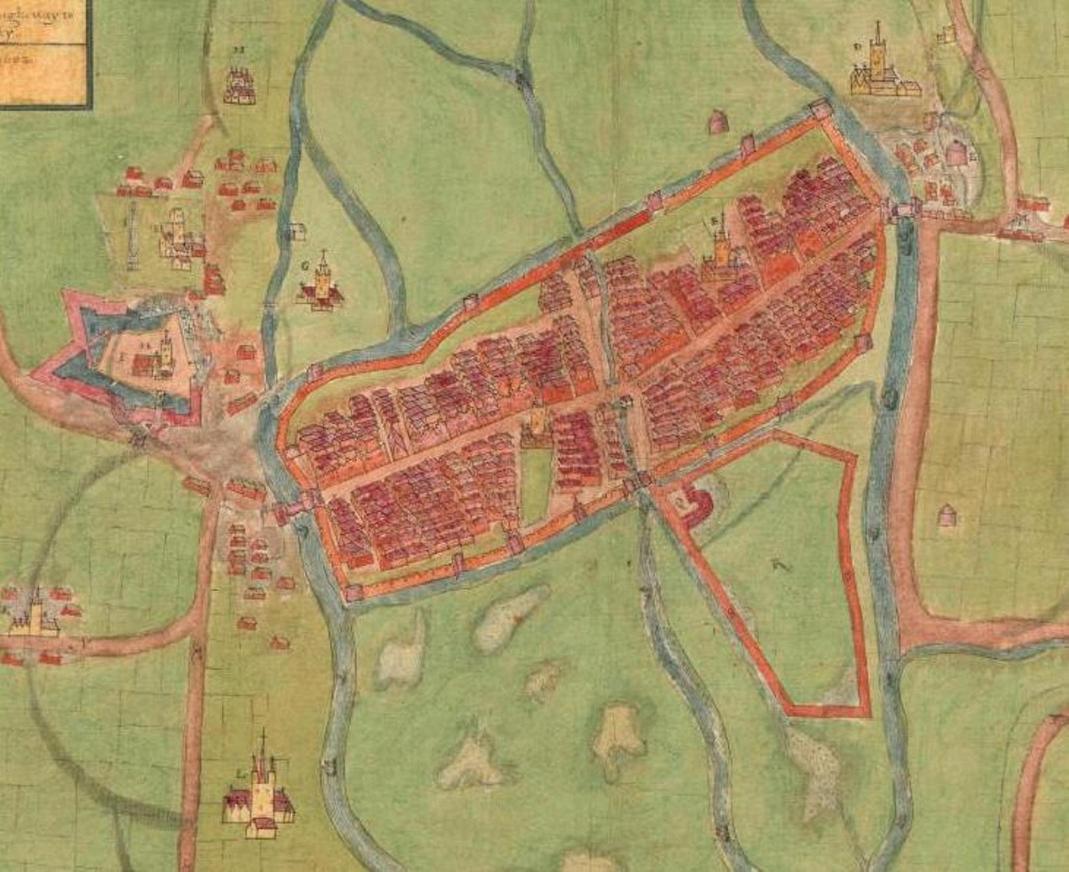

814b. Depiction of Cork Harbour and East Cork from section of John Speed’s Province of Munster, c.1610-11 (source: Cork City Library)

Winter 2015, Cork City Council Parking Initiative in Cork City Centre

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 8 October 2015

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 8 October 2015

Cork Harbour Memories (Part 32)

The Theatre of Empire

The online map archive of the city through the ages makes for great viewing at www.corkpastandpresent.ie. The early seventeenth century is well represented. One beautifully engraved and hand-coloured map is by John Speed (1552-1629) of the province of Munster taken from The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine (1611-12). In the corner of the map is a representation of the walled town of Cork. Though dated 1610 and mentioning London based publishers John Sudbury and George Humble. It was 1616 before it was actually published in Amsterdam by globe maker and map engraver Jodocus II Hondius with the assistance of George Humble, who also acted as Speed’s editor. Sudbury and Humble were the largest and most successful publishers and print-sellers in London.

The Munster map is embellished with an engraving of a man (a cartographer?) wielding a large pair of dividers, while he stands on top of the scale of Irish miles; in Youghal harbour is a galleon ship and in the Atlantic is a boy playing the harp whilst sitting astride a remarkable winged sea creature. Present day Munster comprises six Irish counties but the province has to this day many churches and ancient castles that are depicted on this map. The map abounds with the names of local clans and families – it is inscribed in a very personal way – but its use was also political showing the controlled hidden corners of the British empire.

There are two inset town plans on the map of the most prominent towns in the province at the time – Cork and Limerick, both of which were fortified with large town walls and built on rivers. In the Cork map, the northern suburbs, present day Shandon Street is shown along with Shandon Castle and the remains of the Franciscan Abbey on the present day site of the North Mall. In the southern suburbs, structures such as the Augustinian Abbey, the earthen ramparts of Elizabeth Fort, while further west an old medieval church associated with the remains of a round tower encompassed by a wall are depicted.

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography records that John Speed as beginning his working life as a tailor in the northern English county of Cheshire. He pursued his apprenticeship under his father, a local tailor, and carried on the family business for a number of years. His attention to detail and a keen interest in cartography, led him to try his hand at map making. He began to display a uncharacteristic talent for this and, despite still working as a tailor, Speed created and published his first known map in 1595 – a map of Canaan.

Soon afterwards, Speed was patronised by Sir Fulk Revil, It was this generosity that allowed Speed to depart for London, still as a teenager, and focus on his education at the College of Antiquaries. He became absorbed in his studies, developing his keen interest in history, and soon a specialist interest in the history of cartography. With the help and advice of various associates of Sir Fulk Revil, he pursued the notion of creating a complete and precise atlas of the British Isles.

Speed took the first step with his home county of Cheshire, completing the map with one of the earliest town plans of Chester with arms and vignettes which were to become his signature style. Engraved by William Rogers, this map was published individually in 1604. He continued to cover all the counties of England and Wales. The resulting atlas, finally published in 1612, was titled The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine. This remarkable work was published in partnership with the already established house of John Sudbury and George Humble. The atlas, bought by the University Library in 1968, is now considered priceless. It contains a single sheet for each county of England and Wales, plus a map of Scotland and each of the four Irish provinces, and paints a rich picture of the countryside at the turn of the seventeenth century. Cambridge University Library is home to one of only five surviving proof sets. Their map department elegantly describes Speed’s maps: “Rivers wriggle through the landscape, towns are shown as huddles of miniature buildings, woods and parks marked by tiny trees and – with contour lines yet to be invented – small scatterings of molehills denote higher ground”.

The ‘Theatre’ was a great success and was published again many times and by a number of publishers: Sudbury and Humble notably published their second edition of The Theatre in 1627, the last edition to be published before Speed died. In 1627, Speed released his other major work: A Prospect of the Most Famous Parts of the World. This finely detailed and embellished world atlas, the result of many years development alongside The Theatre, includes the notable accolade of being the first world atlas to be published by an Englishman. The Prospect was to be his last major work. John Speed died on 28 July 1629 having created some of the most remarkable cartography.

To be continued…

Captions:

813a. Section of John Speed’s Province of Munster, from Speed’s The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine, c.1610-11 (source: Cork City Library)

813b. John Speed’s ‘Corke’ from his Province of Munster (source: Cork City Library)

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article, 1 October 2015

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 1 October 2015

Cork Harbour Memories (Part 31)

The Construction of Elizabeth Fort

Continuing on to explore the old maps of the City, the colourful Plan of Cork c.1600 based in the Hardiman Collection in Trinity College Dublin places an emphasis on an ordered walled town on a swamp complete with houses, laneways, drawbridges. Commissioned by George Carew, President of Munster or the plantations within the south of the country, this is the second of two known maps of the walled town by him. In this plan the emphasis is less on the height of the walls and more on the roads leading into the settlement. It shows a new dock area to the east to accommodate increased trade. But it is the showcasing of Elizabeth Fort on the left (with the Holy Rood Church within), which is perhaps why this map might of been created.

Due to the stand-off in the Battle of Kinsale between English and Irish and Spanish, a reference in State Papers from late 1601 details Carew paid 200 labourers to expand an extensive trench in the southern suburbs, and that the project was paid by the walled town and the English administration in Ireland. A further reference in the State Papers from Carew to Lord Mountjoy on 6 August 1602 reveals Carew’s interest in creating the large earthwork; “That irregular work your Lordship saw at the south end of Corke, first intended for no other end than a poor entrenchment, for a retreat, is now raised to a great height equal or above all the grounds about it, and so reinforced with a strong rampart, as a powerful enemy shall not carry it in haste, and whilst that work holds out it shall be impossible for an enemy to lodge near that end of the town. The work is great, the Queens charge in erecting it nothing”. References in the same papers also mention the construction of a new fort at Kinsale (in time to become James Fort) and a fort on Haulbowline Island in Cork harbour.

In April 1603, Queen Elizabeth I died and a new protestant king James I was proclaimed. The Council Books of the Corporation of Cork relate that in the case of Cork, a Captain Morgan was given the responsibility by the lord lieutenant of Ireland, Deputy Mountjoy to relate the news. In Cork, the message was received by a George Thornton, one of the Kings’ appointed commissioners for Munster who gave the news to the mayor of Cork, Thomas Sarsfield. In those days, due to previous charters, the mayor and the citizens of any royal town had the choice of refusing to proclaim a new monarch on the English throne but it rarely occurred due to the threat of military force. However, in this case, the mayor, Sarsfield was anti the crown and in favour of the rebellious Irish living in the area. He knew that he could not outright refuse but decided to use niches in the political system to delay the process of proclamation.

Sarsfield took his right to call together elected officials of the Corporation at the city court house to decide on the matter. During this time, he was informed that the rest of the large walled towns had proclaimed James and kept Thornton, the English commissioner who was waiting for a response outside the meeting. Sarsfield managed to delay the process further by declaring that the meeting had to be adjourned until the following day. Under the pressure of time, Sarsfield and the citizens contemplated attacking a fort at Haulbowline but agreed on arming themselves and preventing any English forces from entering the town.

This rebellion did not deter Thornton from carrying out and at this stage enforcing the proclamation that James I was the new king. Thornton and eight hundred soldiers proclaimed the new king in the north suburbs of the city around Shandon Castle. A number of principal characters are recorded in this revolt. One such man, a Thomas Fagan had an interesting personality. One incident involving Thomas included the time he fired a cannon at an Englishman, a James Grant. He had previously attacked Grant and stripped him of his clothes. Fagan was also responsible for breaking into the city’s ammunition store within a former tower house called Skiddy’s Castle. This store was located at the northern end of North Main Street, now the site of the National Rehabilitation Board. However, firing cannons at people, raiding gunpowder stores were only one part of his personality. Fagan also carried a white rod around the city and declared himself the principal church-warden in the city. It is recorded that any English person or protestant that passed him was mocked without fail.

Even, certain Englishmen took the side of the rebels. John Nicholas, brewer and a John Clarke, tanner mounted a small portable cannon on top of the walls and fired at two soldiers, killing them. The town’s recorder, John Mead was also on the side of the rebellion and used his political clout accordingly to support the rebels. Mead ordered the king’s store keeper, an Allen Apsely at Skiddy’s Castle to be killed and his arms to be taken away. He also ordered the arrest of the clerk of the munitions, a Michael Hughes along with his wife who were sentenced to be thrown over the walls as a means of execution.

To be continued…

Captions:

812a. A description of the Cittie of Cork/ Plan of Cork, circa 1602 by George Carew (source: Hardiman Atlas, Library of Trinity College Dublin)

812b. Elizabeth Fort from A description of the Cittie of Cork/ Plan of Cork, circa 1602 by George Carew (source: Hardiman Atlas, Library of Trinity College Dublin)

Cllr McCarthy’s New Book, North Cork Through Time

The second of three books Kieran McCarthy has been involved in penning this year focuses on postcards of historic landscapes of North Cork. Entitled North Cork Through Time, it is compiled by Dan Breen of Cork Museum and Kieran and published by Amberley Press.

The region is defined by the meandering River Blackwater and its multiple tributaries and mountainous terrain to the north. It borders four counties that of Kerry, Limerick, Tipperary and Waterford. The postcards, taken for the most part between c.1900 and c.1920 show the work of various photographers, who sought to capture the region and sell their work to a mass audience. Not every town and village were captured in a postcard. This book brings together many of the key sites of interest and serves as an introduction to the rich history of the region. In the postcards, one can see the beauty that the photographers wished to share and express. The multitude of landmarks shown in this book have been passed from one generation to another, have evolved in response to their environments, and contribute to giving the County of Cork and its citizens a sense of identity and continuity.

Chapter one explores the border territory with County Kerry – a type of frontier territory for Cork people – its history epitomised in the elegant and well-built Kanturk Castle, the gorgeous town of Millstreet with its international equestrian centre and its access into the old historical butter roads of the region. Chapter 2 centres around the Limerick Road from Mallow to Charleville – Mallow a settlement with a heritage dating back 800 years and straddles the winding River Blackwater.

Chapter 3 glances at the area east of the Mallow-Limerick Road taking in the stunning Doneraile estate with the adjacent and spacious streetscape of the connected village. Killavullen, Castletownroche and Kilworth all present their industrial pasts. Mitchelstown stands in the ‘Golden Vale’ of the Galtee Mountains, its heritage being linked back to the Kingston estate and their big house, which dominated the local landscape with views on all it surveyed. Chapter 4 explores Fermoy, which because of its history and connection to a local military barracks possesses a fine range of postcards. Its bridge and weir, views of the Blackwater, the nineteenth century square, colourful streetscapes all reveal the passion for such a place by its photographers. North Cork Through Time by Kieran McCarthy and Dan Breen is available in any good bookshop.

Kieran’s Question to the City Manager/ CE and Motions, Cork City Council Meeting, 28 September 2015

Question to the CE:

To ask the CE on an update on the Penrose Quay hoarding? Whilst acknowledging, the recent creation of a smaller hoarding space, it is now six years since my initial asking of when this remnant of the Cork Main Drainage Project will be completed and the site levelled off (Cllr Kieran McCarthy)

Motions:

To add the footpaths of Oakfield Lawn, Ballinlough Road to the footpath renewal programme (Cllr Kieran McCarthy)

That the Council engage with the European Capital of Innovation programme with a view to attaining such an accolade. The programme celebrates the European city which is building the best “innovation ecosystem”- connecting citizens, public organizations, academia, and business – with a view to helping the city scale up its efforts in this field – all of which Cork and its region have in abundance (Cllr Kieran McCarthy).

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 24 September 2015

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 24 September 2015

Kieran’s North Cork Through Time

It’s been a very busy year. The second of three books I have been involved in penning this year focuses on postcards of historic landscapes of North Cork. Entitled North Cork Through Time, it is compiled by Dan Breen of Cork Museum and I and published by Amberley Press.

It is easy to get entangled with the multi-storied landscapes of North Cork. It is a region with so many stories to tell, veins of nostalgic gold from tales of conquest to subtle tales of survival. There are many roads to travel down and many historical spaces to admire. The enormous scenery casts a hypnotic spell on the explorer. The region is defined by the meandering River Blackwater and its multiple tributaries and mountainous terrain to the north. It borders four counties that of Kerry, Limerick, Tipperary and Waterford. The postcards, taken for the most part between c.1900 and c.1920 show the work of various photographers, who sought to capture the region and sell their work to a mass audience. Not every town and village were captured in a postcard. This book brings together many of the key sites of interest and serves as an introduction to the rich history of the region.

In the postcards, one can see the beauty that the photographers wished to share and express. The multitude of landmarks shown in this book have been passed from one generation to another, have evolved in response to their environments and contribute to giving the County of Cork and its citizens a sense of identity and continuity. Cultural heritage does not end at monuments and collections of objects. It also includes traditions or living expressions inherited from our ancestors and passed on to our descendants. Pilgrimages and rituals are also engrained in many of the scenes within the postcards. Even mundane performances can construct a historic past and help weave personal and local memories with established national and regional historical narratives.

In many of the postcards, the scene is set up to elicit a response and to create a certain emotion within us, or because they make us feel as though we belong to something – a region, a country, a tradition, a way of life, a collective memory, a society. North Cork is blessed with such an array of diversity in heritage sites and there is a power in that diversity.

Chapter one explores the border territory with County Kerry – a type of frontier territory for Cork people – its history epitomised in the elegant and well-built Kanturk Castle, the gorgeous town of Millstreet with its international equestrian centre and its access into the old historical butter roads of the region, the use of secondary rivers for transport and industry, and the development of railways lines.

Chapter 2 centres around the Limerick Road from Mallow to Charleville – Mallow a settlement with a heritage dating back 800 years and straddles the winding River Blackwater. The town came into its own in the nineteenth century with the development of its main street, churches, academies, convents, viaduct, clock tower and spa house, all interwoven with the commemoration of Ireland’s famous writer and poet, Thomas Davis. The idea of an interwoven and multi-narrative heritage is also present in Buttevant. A former walled town, its medieval fabric is shown in its streetscape and old tower, Franciscan church and the ruinous Ballybeg Abbey in the town’s suburbs. On the latter site its columbarium or pigeon house reminds the visitor of the importance of seeing the human side of our heritage – that people minded the birds and in a cherished way created the house with all its square roosts. Charleville also connects to an English colonial past being a late seventeenth century plantation town named after Charles II.

Chapter 3 glances at the area east of the Mallow-Limerick Road taking in the stunning Doneraile estate with the adjacent and spacious streetscape of the connected village. Killavullen, Castletownroche and Kilworth all present their industrial pasts. Along the Blackwater, Ballyhooley Castle stands in defiance of time, as does Moorepark and Glanworth Castles, just off the old Fermoy-Mitchelstown Road. The nineteenth century estates are very prevalent in old stone walls, old ruinous and rusted gateways. There are exceptions such as Castlehyde, which stands as a testament to the affection of the Flatley family, the current guardians of its heritage, but also a salute to the many families who inherited such estates and landscapes. Mitchelstown stands in the ‘Golden Vale’ of the Galtee Mountains, its heritage being linked back to the Kingston estate and their big house, which dominated the local landscape with views on all it surveyed.

Chapter 4 explores Fermoy, which because of its history and connection to a local military barracks possesses a fine range of postcards. Its bridge and weir, views of the Blackwater, the nineteenth century square, colourful streetscapes all reveal the passion for such a place by its photographers. Still today, you can almost hear the hoof noises and creaking carriage wheels of the Anderson coach works and the marching of the military in the now disappeared army barracks. Above all Fermoy through its heritage exhibits a strong sense of place, a proud settlement, traits which pervade across North Cork and its landscape.

North Cork Through Time by Kieran McCarthy and Dan Breen is available in any good bookshop.

Captions:

810a. Banks of River Blackwater at Fermoy, c.1910 (source: Cork City Museum).

810b. Banks of River Blackwater at Fermoy, present day (picture: Kieran McCarthy)

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 17 September 2015

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 17 September 2015

Thomas Kent Returns Home

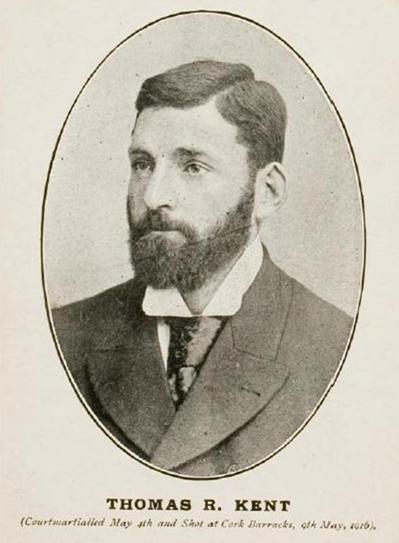

The north Cork village of Castlelyons will come to a standstill on this Friday as it finally welcomes home the remains of Thomas Kent, who along with Roger Casement was the only person outside of the capital to be executed in the aftermath of the 1916 Rising. Following his execution by firing squad at Cork Prison on 9 May 1916 Thomas Kent’s remains were interred in an unmarked grave within the prison compound.

For almost a century the exact location of his resting place remained a mystery. His family had long campaigned for Thomas’ grave to be identified so that he could be re-interred at the family plot in Castlelyons. This became possible after documents, kept secret by the British for almost a century, were released identifying his grave. Remains exhumed following an exhaustive investigation led by the National Monuments Service subsequently underwent DNA testing by the State Pathologists Office, the Garda Technical Bureau and the UCD Science Faculty and were confirmed to be those of Thomas Kent. The Kent family subsequently accepted an offer by An Taoiseach Enda Kenny of a State funeral for Thomas, which will take place in his native Castlelyons on Friday. On this Thursday evening his remains will arrive to the chapel in Cork’s Collins Barracks. Following a private family sitting, there will be a prayer service, which will be open to the public, from 6.30pm. The chapel will remain open after the service to allow people to pay their respects. On Friday the funeral cortège will depart from Cork Prison with full military accompaniment following a private removal service.

The online exhibition of of the National Library’s 1916 Rising, Personalities and Perspectives outlines that Thomas Kent was born in Bawnard House, Castlelyons, Co. Cork in 1865. His family had a long tradition of fighting against the injustices suffered by small farmers and fought particularly during the Land War. When Thomas was 19 he emigrated to Boston where he settled for some years working as a church furniture maker until he was forced to return to Cork due to ill health.

Upon his return he spent some months in prison for his involvement in land reform agitation. It was not unusual for a Kent brother to be in jail and the Royal Irish Constabulary spent much time pursuing and keeping under observation the Kent household. After the split in the Nationalist movement due to the Parnell affair the family seem to have slowed their involvement until Thomas joined the Gaelic League and soon afterwards the Irish Volunteers when they were established in 1913.

John Redmond, the recruiting sergeant for the British Army and leader of the Home Rule Party was due to give an oration in the village of Dungourney. The Kent brothers invited Terence MacSwiney to speak on an anti-recruitment platform at the same time. The local GAA members and Volunteers marched through Redmond’s meeting holding their hurleys on their shoulders in simulation of rifles. That evening a company of Irish Volunteers was created in Dungourney much to the consternation of Redmond and the local police. It was only a few weeks after this that the police arrested and remanded Thomas. Despite their best efforts he was found not guilty but the police raided Bawnard House a few days after his release and discovered weapons and ammunition. Thomas Kent was sent to prison again, this time for two months.

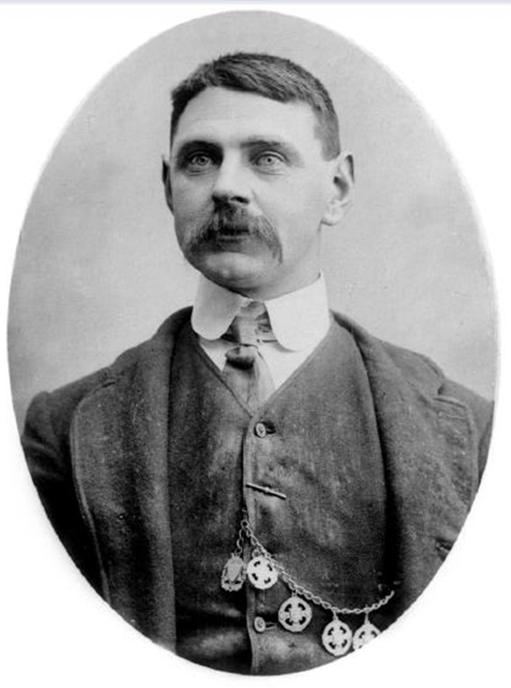

Later, when news of the Rising in Dublin reached the Kent brothers they lingered in some neighbouring houses for orders to mobilize. These orders never came due to MacNeill’s countermanding order and to the fact that J J O’Connell came to Cork with the order to stand down. By 2 May, four of the brothers, Thomas, William, Richard and David returned to Bawnard House. At dawn, the police came to the house with orders to arrest the whole family. They had encircled the house and called for the four brothers to come outside. Thomas replied that they were soldiers of the Irish Republic and that there would be no capitulatation. To this the police replied with a volley of shots. For the next three hours a battle followed but the Kent’s, with only three shotguns and one rifle to their name, ultimately ran out of ammunition. Mrs. Kent was in the house throughout the battle and not only gave great encouragement to her sons but helped to clean and cool their weapons.

The outcome of the fight was that one of the brothers David was wounded and a Head-Constable was killed. In the confusion of the Kent’s surrender, the athletic Richard made a dash for the woods rather than return to prison. He was killed in a fusillade of RIC rifle fire. The constables put the two remaining brothers who could stand up, against a wall, and were going to shoot them but for the intervention of a military officer. On 4 May, William and Thomas were court-martialed. William was acquitted but Thomas was convicted and sentenced to death for taking “part in an armed rebellion…for the purpose of assisting the enemy”. Thomas Kent was executed by the British in Cork Detention Barracks on 9 May 1916.

Captions:

810a. Thomas Kent (picture: National Library of Ireland)

810b. Richard Kent (picture: National Library of Ireland)

Kieran’s Question to the City Manager/ CE and Motions, Cork City Council Meeting, 14 September 2015

Question to the CE:

To ask the CE for an update on the Blackrock regeneration pier project and the work to be pursued very shortly? (Cllr Kieran McCarthy)

Motions:

That the Council engage with the European Region of Gastronomy Programme with a view to attaining such an accolade. The European Region of Gastronomy Award is given to regions that commit to a programme of events designed to promote distinctive food cultures, educate for better health and sustainability, and who stimulate gastronomic innovation – the latter of which Cork and its region have in abundance (Cllr Kieran McCarthy).

That a sustainable programme of work be put in place to tidy up (overgrowth, fallen stones, broken wrought iron work) the nineteenth century parts of St Joseph’s Cemetery, which are in a dreadful state. Can the Council work with the Prison service and the community work scheme to keep such historic spaces tidy? (Cllr Kieran McCarthy).