Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 15 October 2015

Cork Harbour Memories (Part 33)

A Busy Seventeenth Century Settlement

Cork in the first decades of the seventeenth century was valued as the third most important port after Dublin and Waterford. The growth in prosperity was mainly attributed to the increase in utilization of the surrounding pastoral hinterland surrounding the city. Large sections of woods were cleared in Munster to accommodate the large demand for pasturalism. However, in 1610, a report by the commission of the Munster Plantation noted that the woods were being depleted too fast in order to clear land so sheep could graze on it.

In the early 1600s, it is recorded that the main areas that Cork was importing from and exporting to included Seville in Spain, Lisbon in Portugal, St Malo and the Saintonge area in the south-west of France, cities in the north of Italy such as Pisa, western English port cities such as Bristol, Cologne and the Rhine area in Germany and towns such as Delft in northern Holland. New trading connections were also established with the Canary Islands and Jersey. The main imports from the first four countries in the above list mainly consisted of wine while from the others iron and salt were the principal imports. This is also reflected in the archaeological evidence from sites with preserved late medieval contexts. A large percentage of the pottery discovered dating to the seventeenth century was from the warm temperate countries where wine was grown.

Hides, tallow, pipestaves, rugs and friezes were the main exports along with cattle, wool and some butter. There was an increasing trade in beef, which led to the moving of slaughter houses or shambles outside the city walls. Indeed, such was the extent of active trade in Cork whether it be exporting or importing, that there was increased activity in the pirate activities. It eventually reached the stage where special convoys were introduced to protect merchant ships especially around the south coast.

The physical nature of the walled city appears constantly in Cork Corporation priority list regarding revamps. The old Corporation records detail the worsening condition of the town walls. In January 1609, a plan to build a new court house on the site of King’s Castle, which was the northern control tower of the central Watergate into the town, was delayed. The walls onto which the courthouse were be attached were crumbling and in danger of collapsing. New walls would have to be built, so the new courthouse could be built.

The poor condition of the town walls continued to be a major issue for the Corporation into the decades of the 1610s and 1620s and even the bridges leading into the town were described as ruinous and calls were made for them to be mended. From 1614 on, all monies earned by the Corporation from taxing imports such as wine were to be spent the repairing of the walls. However, by 1620, it was agreed that the incoming revenue into the settlement’s coffers was not enough and a bye-law was passed where several municipal rates were to be brought in as well as increasing of existing rates. Taxes were raised on several regularly exported commodities such as animal feed such as oats, animal skins such as horse, deer, fox and on drinks such as beer and wine. However, the taxes regarding docking your boat, passage through the city, tax on the land you owned were abolished.

In 1620, an English traveller described Cork as “ a populous town and well compact, nothing to commend it…the town stands in a very bog and is unhealthy”. The physical state of the town also became an issue in May 1622 when lightning struck one of the thatched roofs in the eastern part of the city which caused a large scale fire to rapidly spread from one thatched roof to the next. According to the historical records, the fire began between eleven and twelve o’ clock in the morning. Indeed, apart from one clap of lightning there was also a second clap of lightning which lit the houses in the western part of the city. It is detailed that the since the houses overlooking the main street were in flames, the people trapped between the two fires were forced to flee into the city’s main churches, Christ church on South Main Street and St. Peter’s on North Main Street. Both of these churches are recorded as being constructed of stone and having a slated roof which saved the lives of numerous townspeople. The people who did not make into the churches were unfortunately consumed by the fire itself. In September 1622, an order was passed that the stone walls be built and the roofs be replaced by slate or timber boards.

The early seventeenth century was an era of unprecedented social upheaval whereby a large part of society consisted of a Catholic majority ruled by a Protestant sovereign. As the seventeenth century progressed, Catholicism became more a political movement than a religious one which aligned itself and made full use the church in Rome as a reason for rebellion.

To be continued…..

Captions:

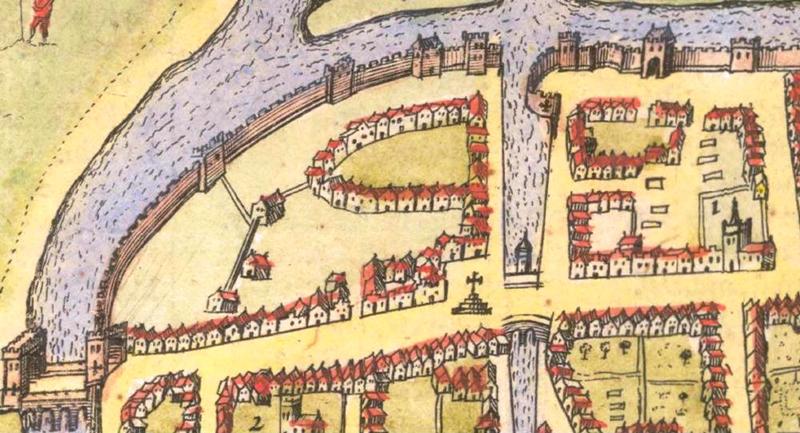

814a. Depiction of Cork’s interior dock, the Watergate complex, from John Speed’s ‘Corke’ from his Province of Munster c.1610-11 (source: Cork City Library)

814b. Depiction of Cork Harbour and East Cork from section of John Speed’s Province of Munster, c.1610-11 (source: Cork City Library)