Trees and Roots:

Madame chairperson, ladies and gentlemen, colleagues, thank you for the invite this evening.

If there was ever a corner of the world, whereby nature always stamps its unique identity it is this corner of the Rebel capital. As each Spring rolls around, the cherry blossom trees in Ballinlough appear as if in defiance of our damp and cold winters and are proof that spring has finally arrived. Spring offers renewal, re-birth, growth, hope, re-imagination and inspiration. The dark evenings end as the daylight lengthens. It’s hard not to romanticise about the blossoms and their effects on all those who drive and walk the local roads.

They add immensely to the sense of place and identity of this area. It’s as if the blooms want to say ‘remember us’, ‘wonder in us’ be inspired; they are in their own way, part of the city’s cultural DNA, a piece of life, a way of life, the trees are always in flux…their roots spreading into the undulating topography of Ballinlough, pushing up, dislodging the footpaths and roads in the park below and in the Japanese gardens.

Cork songwriter John Spillane writes of Cork’s cherry blossoms “as putting on the most outrageous clothes and they sing and they dance around”.

The Vita Cortex workers in their struggle in 2012 commented on the cherry blossoms on Pearse Road;

“They stand tall like us, magnificent in their beauty. They sway in the wind and bend with it but remain unbroken. They have been there lining the street as long as any of us can remember… they are part of the local landscape and history, The cherry blossom trees are like sentries guarding the road to the factory; our home, our workplace”.

The blossom trees offer a fleeting beauty every spring, where you do nod and look in passing. And all too soon the blossoms fall and are relegated to another season passing. And with each bloom, another year comes around and that sense of renewal hits in again.

Casting Shadows:

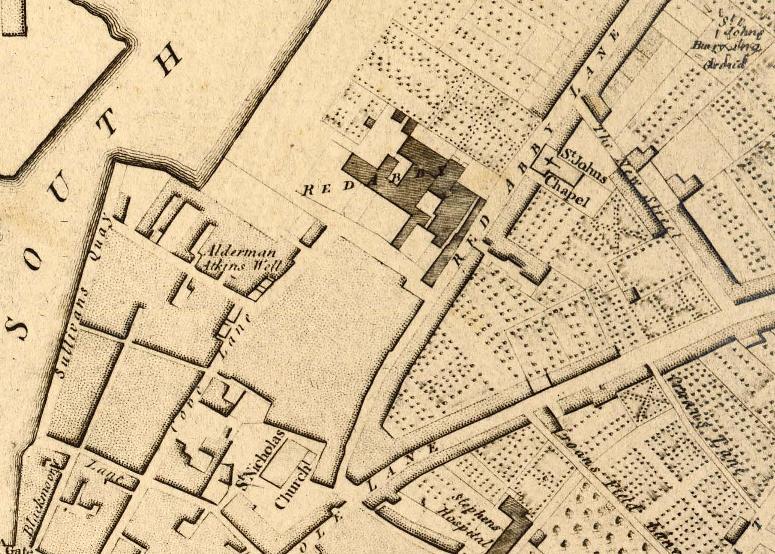

But the blossoms in a place such as the Japanese Gardens were not always there. They cast shadows over the now fading memory of Douglas Nurseries, run by Atkins. Sixty years ago, a Welsh accent wafted in the air at this site as the site Manager Mr Jones went about his work. Mr Wolfe, enthusiastically looked on heading up the operation – the acts of making and nurturing something to grow and sowing seeds. There were 12-14 people working there. One of the lads was an old gentleman, Con O’Sullivan from Ballinlough. Where now St Anthony’s School is, there was a wall across there and that was the boundary of the nurseries. Inside that wall were the fruit trees. The premises extended all the way down to Douglas Road. There were several greenhouses in which tomatoes and flowers were grown. Outdoors, shrubs and fruit trees were also grown. One of the biggest jobs in Atkins was to make the compost. John Innes was a very famous brand in its day and we used to make it from various ingredients.

As the late fifties developed the extent of Wolfe’s acreage lessened. Dave Bradley of Bradley Brothers was also making and sowing seeds in a sense. They were turning one house a week at one stage in the 1950’s and 1960’s. It was amazing how fast they moved. It’s amazing what they created. By the time they were finished one house they were moving onto the next. They built almost 1,500 houses in Ballinlough from Browningstown East, Ardmahon and Ardfallen estate, all the estates with Somerton; they did Beechwood Park and Belmont Avenue. At the top of Atkins, they developed what was deemed the good building land, which became Beechwood by the mid 1960s, fifty years ago. Dave Bradley’s mother liked trees and thought Beechwood would be a nice name for the estate.

Educational and Social Needs:

Meanwhile the local clergy of the new parish of Ballinlough, just five years old in 1960 had their work cut out to embrace their new parishioners, mostly young and white collar workers, who in time gave Ballinlough a youthful population, who kicked ball around Ballinlough’s new roads, sat with Derry Cremin in Jock’s Murphys and discussed tactics for the next hurling match. In its demise, they harnessed the eventual ruins of Atkins for adventures, slocked apples from the various orchards from here, that of Hennerty’s to Kelly’s orchard on the site of The Orchard Bar to further afield and created landscapes of cowboys and Indian across the vast market gardens of Ballinlough.

Fifty years ago, Ballinlough was a relatively young parish and community. It had the usual needs of a young growing community, which are educational, recreational and social. The parish priest of the time, Canon Eddie Fitzgerald, with the help of his priests and people, courageously faced those challenges. Indeed, amongst those young priests who came under the wing of the Canon Fitzgerald was Fr now Canon Michael Crowley.

There were three schools in the parish, Ballinlough old boys school at the Silver Key, and Our Lady of Lourdes in Ballinlough and Crab Lane off Boreenmanna Road. These schools were totally inadequate to cope with the growing numbers of young boys and girls. Thornhill House was bought by the parish to provide temporal classrooms for the overflowing number of boys.

Then Eglantine House on the Douglas Road was bought and converted into a school, opening in 1959. It was seen as a temporary solution to the growing number of girls in Ballinlough and surrounding areas. So great was the demand for places that stables in the yard belonging to Eglantine House had to be converted into classrooms. In time this temporary school was replaced by a new beautiful Eglantine school and the beautiful tree, which beset the ground was removed.

St Anthony’s School:

The local Canon Fitzgerald, who was an elderly gentleman, had multiple interests especially in education. He became the first parish priest in 1955. His grandfather was Lord Mayor of Cork, Sir Edward Fitzgerald. He was the key instigator of the Cork International Expedition on the Mardyke in Cork City in the years 1902 and 1903. Energy and foresight ran in the Fitzgerald family. On one morning in the early 1960s, he and his curate, Fr Jeremiah Hyde set off searching for a new site for a boys school. They agreed that perhaps the upper half of the property of formerly Atkins Nursery could be built on. By the early 1960s the property had become that of Cork Corporation. Fr Hyde drove the Canon to Cork City Hall where he had a chat with city planners and the idea for the site of St Anthony’s School was born. People got together and raised funds for this new school, which we all now know as St Anthony’s. The rest is history with school celebrating its fiftieth anniversary this year.

By the late 1960s, Ballinlough National School for boys as such was spread out in different buildings. You had the new building of St Anthony’s, Thornhill House, and there was the old national school near the Silver Key bar. Jack Corkery was the principal and his wife was principal in Eglinton School, which had opened in 1959. With the St Anthony’s complex, there were about eight or nine on the teaching staff. Vice-Principal Bart Whooley was also a respected teacher.

Fifty years ago, the more relaxed confirmation process we enjoy today was more formal with Bishop Lucey sweeping through putting the sixth class to the test on all matters Godly. A stern man but ambitious for the city’s new suburbs with his amazing and architecturally exciting Rosary churches, coupled with schools and community centre. In the late autumn of 1959 while in the United States, Bishop Lucey, Bishop of Cork and Ross, impressed by the work of many Parish credit unions he saw in operation. During the visit he collected as much information as possible on the principles and practices of credit union. On his return to Cork, Bishop Lucey used every opportunity to promote the concept of a credit union.

Fifty years ago, in the late summer of 1965 Fr John Ryan of Our Lady of Lourdes Church called a meeting with John Corkery, Dermot Kelly, and Paddy Hennessey in Thornhill House to sound out the idea of forming a credit union in Ballinlough. All agreed that it was an excellent idea and an immediate start was agreed upon. A working group consisting of five members attended a further meeting in September of 1965. The credit unions already established in the city, had initially started up study groups to explore the possibility of introducing the philosophy of credit union to their parishioners. It was agreed to follow this formula in Ballinlough, and that membership of the group would be by invitation only.

The first meeting of the study group (by invitation only) was held at Thornhill House on 16 November 1965. There were twenty-two people, all male, in attendance and there was a pretty wide representation consisting of tradesmen, factory employees, clerical workers, a clergyman, school principal and a member of the legal profession. This represented a well-balanced reservoir of talent. Fr Ryan was proposed as group chairman and Paddy Hennessey as secretary. Fr Ryan agreed to act as chairman if the position rotated at each subsequent meeting.

The Weight of History:

The roots of all these seeds from fifty years ago – the houses, estates, schools, the credit union – like the roots of the blossom trees run deep. The weight of history, past events, glory days, the voices and stories of thousands of individuals who have come through the driveway gates of houses, our schools, our Credit Union are all important to this area’s identity and sense of place – their roots remain strong fifty years on this year and needs to be continued to celebrated, explored and the lessons and messages of the past brought to bear in forging a future. The energy and aspiration of fifty years has survived into our time inspiring many community leaders in our time and they have the potential to inspire more.

As we enter the lead –up to the commemoration of 1916, I think there are messages concerning inspiration will appear more and more in the next year. Just like the power of the blossom trees, threads such as renewal, re-birth, growth, hope, re-imagination and inspiration will spread through the nation’s psyche in the next few months.

Thank you for your continued courtesy towards myself. You always learn something new about yourself in Ballinlough, indeed here is a place where you get stopped on the road for a chat, are challenged, encouraged, supported, helped and always pushed!

I would also like to thank the people of Ballinlough for their interest and support in my own community projects over the last six years now.

The Discover Cork: Schools’ Heritage or Local history project

The local history column in the Cork Independent, in the books I have been lucky to publish.

the community talent competition, which I have audition for

The Make a Model Boat Project on the Atlantic Pond, which is on 31 May,

and the walking tours through this ward; there are now ten of these – developed over the last number of years –

As a new project to this great city, I have set up a musical society, Cork City Musical Society, so I’m directing and producing my first musical in early June in the Firkin Crane in Shandon. Also recently I have been appointed by the Minister of Environment as an Irish delegate to the EU’s Committee of the Regions, which meets in Brussels every six weeks for two days. The 350 member committee gives advice to the European Parliament on local authority issues. So hopefully there will be something there I’ll find that will benefit Ballinlough or share the positive community projects that go on here with other EU countries. I sit on two committees or commissions, the EU budget assessment committee, and the culture and youth unemployment one, so there is alot there to debate and bring about change in the wider picture again.

I think as an area in the Council Ballinlough was lucky before the economic crash in attaining as much as it could in physically making it a great place – In the last five years the Council’s coffers have been slashed by 45 million euros– something that can be seen visibly on our streetscape – roads decay and crumble, hedges become overgrown, Douglas Pool has not been dealt with to make it into the place that this area needs; these are uphill battles as a Council we face and we must find solutions. All the old parks are rebooting with young families, our schools are packed to capacity, you can see that with the traffic chaos every morning and afternoon. I think as an area we need a proper playground and a multi-use games arena, which is something I continue to fight for in City Hall.

I found last year in the canvass that the older people are being looked after by family and neighbours but do yearn to have a chat to people. The feedback I am getting is that there is certainly a need for a drop-in centre once a week or fortnight – perhaps in this building or in the church. There is certainly a need to hold and continue the work of the Meals-on-Wheels, the bowls Club, our tennis club, and the work of our youth club. The lack of volunteers coming forward is always apparent; we also need to have a chat to the secondary schools on the parish’s borders to build a new audience as such of interested volunteers.

We have been fortunate with the top table’s leadership over the past 7-8 years. That been said I would like to see a change of the guard – keep the organisation moving in a fresh way. I think it has been great to see many organisations getting their chance at holding the chairperson position; I would like to see someone from the Youth Clubs getting a go and seeing what they can muster as the association climbs through renewal in our country. I think new blood would renew the association’s partnership with the community as well. I say this in a respectful manner and not to offend people.

I’d like to thank the various organisations represented here for all their hard work. It is no easy task but one I know you deem important to pursue.

Best of luck in the year ahead – the more optimism and solutions that are radiated from this hallowed community space and grounds the better in these times. In these AGMs, there should always be the sense of thanks and just like the blossom trees a renewal of spirit. Thank You.

Ends

Reference:

McCarthy, K, 2013, Journeys of Faith, Celebrating 75 Years, Our Lady of Lourdes, Ballinlough, Cork.