Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 16 April 2015

Cork Harbour Memories (Part 19)

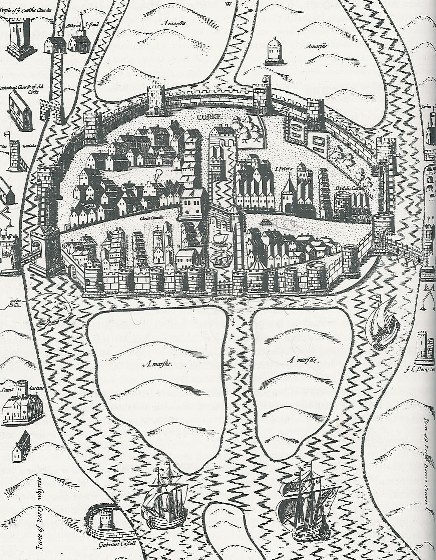

Tudor Ships on the Lee

George Carew’s Map of Cork or plan of the walled town of Cork is different to that of Muskerry. Dated to the late sixteenth century, sometime in the 1590s perhaps, the map depicts numerous structures, which emphasise Cork as a port and a place to be protected as an English outpost of trade. The town walls, the Tudor ships, and the suburban features such as abbeys and watch towers show a town prepared for any potential attack and the difficulties of an attack. The river is presented as an integral feature around which the plan is defined. Like the Map of Muskerry, it is an English-made map to control territory. Here a militarised maritime zone is depicted.

At the heart of the map is Watergate, Cork’s central maritime gate with its associated port, dock and custom house. It would have been impressive in its mechanism in opening to leave ships in. The gate allowed access into a private world of merchants and citizens. The masts of ships moored would have creaked as they knocked against the stone quays. Built between two marshy islands, in the middle of a walled town, its entrance was between the two castles – King’s Castle and Queen’s Castle. Castle Street now occupies a section of the interior dock.

Carew in his map places an emphasis on two Tudor style galleons at the base of his plan – one revealing its starboard side and the other its port side – both have their sails filled with wind – lines, ropes and ladders are almost frozen in an action to move; canons appear through the port holes as if ready for attack. The depiction of the two ships like this can only be speculated upon. Certainly the ships symbolise the link to the protection of the waters of the town and the wider harbour and the role of the English and local navy in its protection. They were symbols of Cork’s presence in a north-west European maritime culture. They were a reminder that to enter the River Lee estuary you would be met by force. Your ship was probably watched from the harbour mouth all the way up the Lee Estuary to the walled town.

The reality of these galleons was far from comfort. The map does not show the enormous amount of crew needed to manoeuvre such ships. These vessels were large ocean going ships, four times as long as they were wide. They had a special deck for cannons. They were broad, slow and not very manoeuvrable. All year round, the interior of a galleon was damp, with a strong smell of tar, stagnant water and sweating unwashed me. For the most part, they were also dark. On the main deck, the only light came from openings in the centre of the deck, from ventilating hatches above each gun, or from the gun ports when their lids were open. Other light came only from candles.

In an attempt to find out more about the workings of and symbolism surrounding Tudor ships, in recent months I travelled to Portsmouth to explore their historic dockyard and heritage complex. One of their purpose-built museums gives public access to view the ghostly timber ruins of the Tudor ship Mary Rose. Half of the ship was lifted from the sea-bed in October 1982, and is now undergoing conservation, as well as over 22,000 artefacts found on board, at Portsmouth. This major project provided opportunities to understand the ship, her essence, her weapons, equipment, crew and stores.

The interpretative panels there reveal that the Mary Rose was built at Portsmouth between 1509 and 1511. Named for Henry VIII’s favourite sister, Mary Tudor, later queen of France, the ship was part of a large expansion of naval force by the new king in the years between 1510 and 1515. Warships, and the cannon they carried, were the ultimate status symbol of the sixteenth century, and an opportunity to demonstrate the wealth and power of the king abroad. The Mary Rose remained the second most powerful ship in the fleet and a favourite of the king. She was deemed to be a fine sailing ship, operating in the Channel to keep up links with the last English landholdings around Calais. She was a carrack, equipped to fight at close range.

The Mary Rose was rebuilt in the 1530s. Her 1536 rebuild transformed her into a 700-ton prototype galleon, with a powerful battery of heavy cannon, capable of inflicting serious damage on other ships at a distance. The high castles (combat structures above deck) were cut down, decks strengthened, and she was armed with heavy guns, with 15 large bronze guns, 24 wrought-iron carriage guns and 52 smaller anti-personnel guns. The Mary Rose now had the firepower to engage the enemy on any bearing, and conduct a stand-off artillery battle. Some of the guns were mounted on advanced naval gun carriages, which made them far easier to handle and move on a crowded gun deck. The new emphasis on artillery reflected the mastery of gun founding in England, another development pushed by Henry VIII. It also reflected the need for a naval force to defend the kingdom against European rivals.

To be continued…

Captions:

788a. Conserved remains of Mary Rose, Tudor ship, Portsmouth Historic Dockyard, 2014 (picture: Kieran McCarthy)

788b. Map of Cork, late sixteenth century as depicted in Sir George Carew’s Pacata Hibernia, or History of The Wars in Ireland (1633), vol. 2, opp page 137.