Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 19 November 2015

Cork Harbour Memories (Part 38)

A Defender of Church and Town

The vast estates of the Fitzgeralds, the Earl of Desmond dynasty (see last week), were confiscated in the reign of Elizabeth I, and granted to various English settlers (called planters or undertakers). The names of the new settlers in Ireland who obtained grants of the Desmond estates in Cork and Waterford, were Sir Walter Raleigh, Arthur Robins, Fane Beecher, Hugh Worth, Arthur Hyde, Sir Warham St. Leger, Hugh Cuffe, Sir Thomas Norris, Sir Arthur Hyde, Thomas Say, Sir Richard Beacon and (the poet) Edmond Spencer.

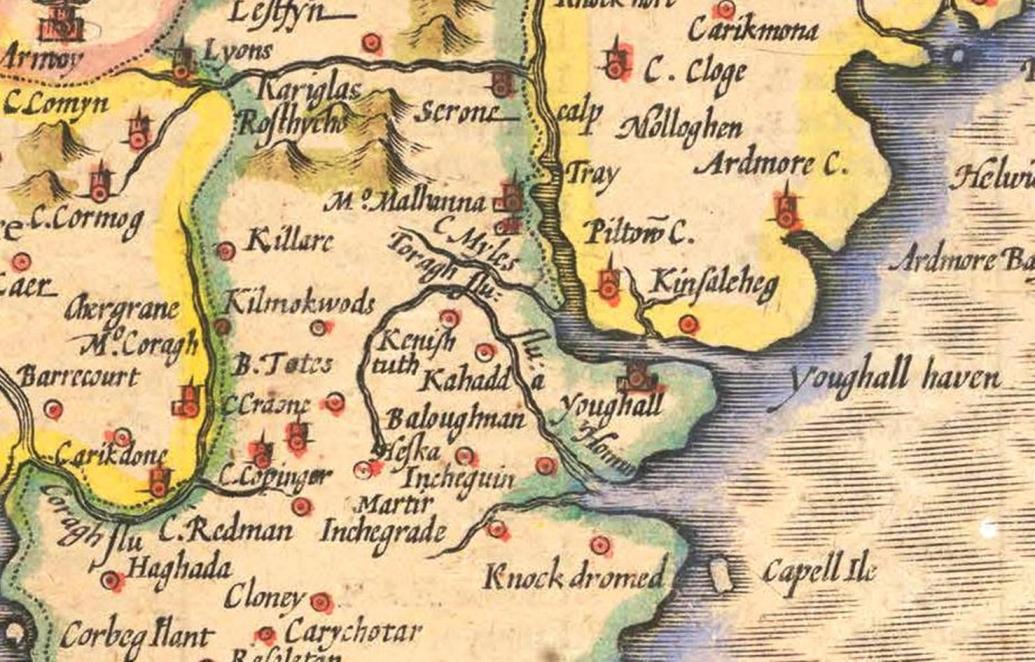

Walter Raleigh (c.1554-1618) had taken part in the suppression of the Desmond rebellion in 1579 and profited from the subsequent distribution of land. He received 40,000 acres or 162 km2 which included the important towns of Youghal and Lismore. This allowed him to become one of the principal landowners in Munster, but nevertheless had only some degree of success in convincing English tenants to settle on his estates. Youghal was the home of Sir Walter Raleigh for brief periods during the seventeen years in which he held land in Ireland. The decade of the 1590s coincided with difficulties on Raleigh’s Irish plantations at a time when his own fortunes were in decline. He sold his Irish estates in 1602 to Richard Boyle, thus ending his involvement with the plantation of Munster.

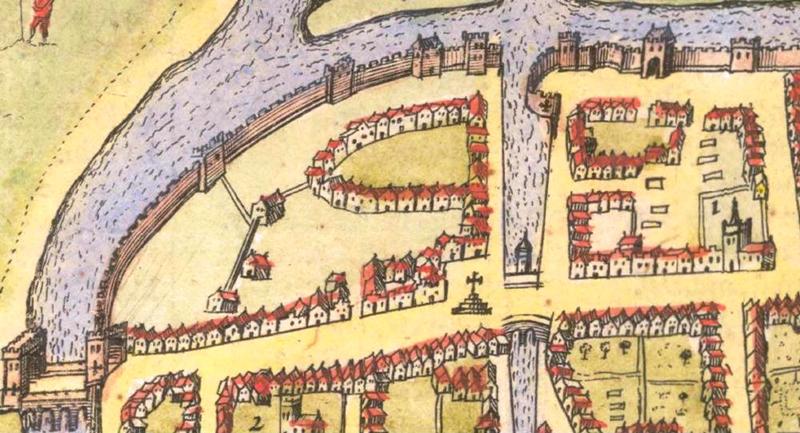

Richard Boyle (1566-1643) is closely associated with the history of Youghal, purchasing the town as part of his acquisition of the Munster estate of Sir Walter Raleigh. On the rich array of heritage information panels in Youghal, the story of Richard Boyle’s influence is related. Boyle occupied the office of Sheriff from 1625 to 1626. He had a substantial residence, known today as The College, close to St. Mary’s Collegiate Church. Boyle recognised the suitability of Youghal area for the production of pig iron, for which there was great demand in England. A plentiful supply of timber for charcoal, rich iron ore deposits, water power and a great port area all combined to generate an active iron industry in the early seventeenth century. The yew woods from which Youghal derived its name (Irish: Eochaill) were used to supply the ironworks of Richard Boyle.

Amongst the other legacies of Boyle’s influence in Youghal are the Almshouses, which he endowed to house six old soldiers, who were to receive a pension of £5 per annum. This service was later broadened to include widows. The six houses were constructed in 1610 and continued in use in their original form until the mid-nineteenth century, when some alterations took place. They are now owned by Youghal Urban District Council and still serve a similar generous purpose.

In 1606 Richard Boyle paid for the south transept of St Mary’s Church to be rebuilt, as a mortuary chapel for his family. Boyle’s journals record that the south-transept was the place ‘wherein the townsmen in time of rebellion kept their cows’. In subsequent years he spent thousands of pounds on the restoration of the church, including rebuilding the chancel. Historian Dr Clodagh Tait in an article in the Royal Irish Academy has an article entitled Colonising memory: manipulations of death, burial and commemoration in the career of Richard Boyle, first earl of Cork. Dr Tait describes the Earl of Cork’s “energetic tomb-building”, which cost him well over £1000, was a means of demonstrating that “he had arrived, and had created a fortune and a dynasty”. Boyle symbolically presented himself as the “spiritual successor of Youghal’s ancient inhabitants”, and as the “defender of the town and its church”. Viewing the relaxed sculpture on his tomb of a smiling Boyle lying on his side with his family around him shows how he did manipulate the meanings around how he was to be commemorated in history.

Architect Alexander Hillis of London erected Boyle’s tomb in the south transept in 1620. The monument, heavily influenced by renaissance architecture, was the height of fashion when it was built. The work is still surrounded by its original protective wrought-iron railings displaying further pieces of family heraldry. The swords shown at the bottom are a symbol of Boyle’s power, justice and the armour of God. It shows Boyle himself reclining, with his first and second wives, Joan Apsley and Katherine Fenton respectively, to either side, his mother Joan Naylor over, and a few of 16 children, kneeling in a row in front of him. His first wife died in childbirth and she is represented with a baby at her feet. The skulls portray someone already dead at the time the monument was carved.

Boyle himself died in 1643 and was buried here in his monument with his mother – but not his wives. Incidentally, a further elaborate monument by Boyle can be found in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin. It was erected to Katherine Fenton, his second wife (died 1630) and finished in 1632. Boyle’s second wife Catherine Fenton bore him fifteen children before she expired at the age of 42. Of the eight daughters, seven were married to noblemen. Of the seven sons, four were ennobled in the lifetime of their father. The most notable of this extensive offspring was Robert Boyle, the natural philosopher and author or Boyle’s Law.

To be continued…

Captions:

819a. Richard Boyle’s tomb, St Mary’s Church, Youghal (pictures: Kieran McCarthy)

819b. Detail of Richard’s face, Richard Boyle’s tomb, St Mary’s Church, Youghal

819c. Richard’s children in sculpture, Richard Boyle’s tomb, St Mary’s Church, Youghal