Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 25 February 2016

Cork Harbour Memories (Part 50)

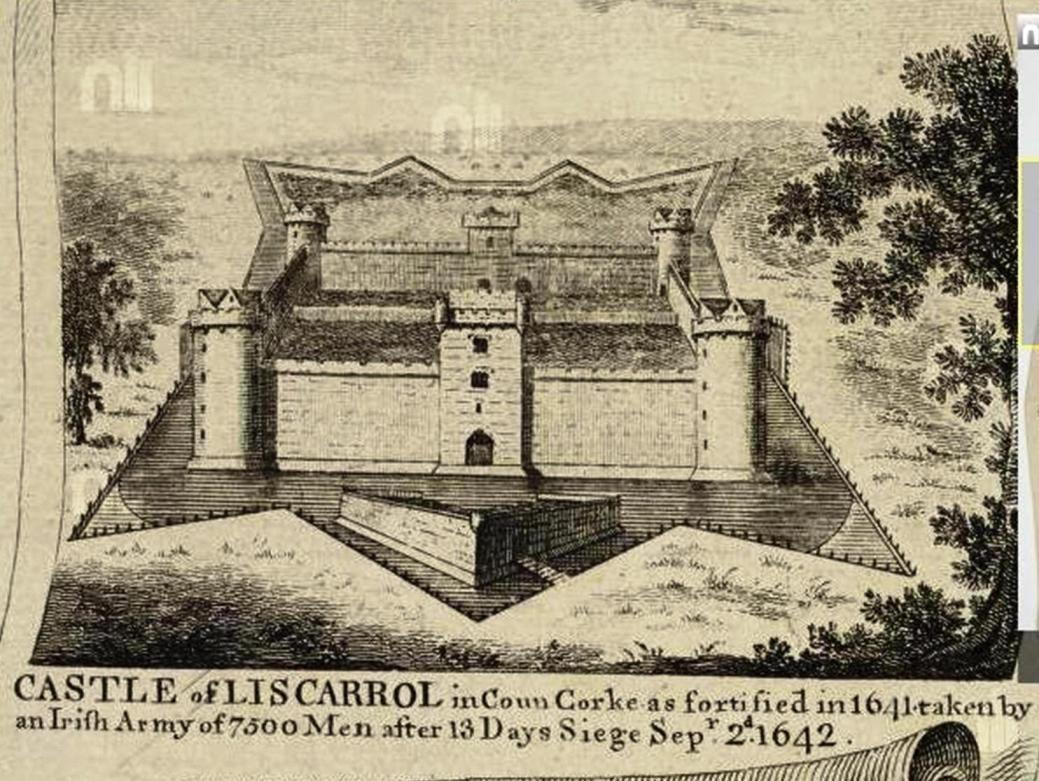

The Battle for Liscarroll Castle

The Confederate army in their first incidents of war in late 1641 cleared Kilkenny and Tipperary of the English recently planted there (see last week’s column). It was decided to march to Cork to try and take the county and city. The Roches, McDonagh McCarthys, O’Callaghans, O’Keeffes and Magners joined the swollen ranks of the Confederates at Two Pot House. Fast forward through campaigns in Limerick and its region, and towards the end of August, 1642, General Garret Barry had moved into Cork and advanced on Liscarroll Castle at the head of an army comprising 7,000 men, 500 horse, a train of artillery and a giant battering ram.

Much is written on the history of Liscarroll Castle. I draw upon the information panels by Dúchas, the Heritage Service at the site, and general historical journals of Charleville and Buttevant, and articles by historians Denis O’ Connell and Edward Garner. All highlight that the structure was developed by the Barry family and is one of the top five of Ireland’s largest thirteenth century castles. It has 30 feet high walls, five great towers and an impressive gateway set in the south wall. In 1637 the structure came into the hands of Sir Philip Perceval as part of a grant from King Charles I. By 1641 Perceval had carried out extensive fortifying work, garrisoned the castle and placed it in the charge of Sergeant Thomas Raymond. Raymond figures quite prominently in the little history known about the stronghold and suffered the humiliation of allowing his charge to fall into the hands of the Irish twice during the wars of the Confederation.

On 30 August 1642 Barry arrived before the castle’s walls at Liscarroll and began to lay siege. Raymond had to face Barry with a garrison of 30 soldiers. Governor of Munster Lord Murrough McDermod O’Brien was 1st Earl of Inchiquin and he was aware of the Irish presence in North Cork, but his forces were not yet near enough to help Raymond. Before the advent of cannon it took surprisingly few to defend a castle against vastly higher numbers, but Raymond’s small force could be no match against the Irish outside the gates.

General Barry placed his precious gun artillery to the south-east of the castle and within three days he had the stronghold in his hands. Raymond did his best and although assured of support from Inchiquin on the next day he felt forced to surrender on 2 September. With the castle now his, Barry decided to march onto Doneraile. However, news came to the Irish general that Lord Inchiquin’s forces were closing in on him and so decided to stand his ground at Liscarroll.

On 3 September 1642, Inchiquin arrived at Liscarroll. Behind him came an army of 2,000 foot, 400 horse and artillery. It was not until his forces were fired upon from the castle walls that he realised that Barry had succeeded in driving back his English horse cavalry. Preparations now began for the major confrontation. Barry had the undoubted advantages. He picked the battle ground, to the east of the castle, and placed the English with the sun in their eyes. Numerically he was much the stronger, but it would be poor discipline that would count against him.

The Irish Army divided into three main bodies, each with about 2,000 men, with the left wing closest to the walls near to the artillery. On the right the Irish cavalry were grouped in a separate body. Inchiquin also divided his army into three main groups. Musketeers formed the right and left with around 800 muskets and pikes in the main centre body. Inchiquin’s cavalry directly faced Barry’s. Artillery fire opened the proceedings, with little or no advantage to either side. An English musket advance received a severe drubbing and retreated back to the lines after an Irish attack. Inchiquin then moved his left wing forward and managed to turn round the Irish right. Following up the advantage of this Irish reverse, Inchiquin’s right wing, under Sir Charles Vasacour now moved onto Barry’s left wing, formed up by the castle’s west wall.

Despite all his advantages Barry lost the day after seven hours of grim fighting. The poor discipline of his forces lost him the day, allowing the English to regroup when under severe pressure. Disciplined smaller numbers defeated larger, less controlled numbers and the Irish were obliged to retreat. Barry suffered the loss of six hundred soldiers, his hard won artillery train, 14 colours, 30 wagons and 300 muskets; the English also lost large numbers.

Liscarroll Castle also featured in lesser engagements in the Confederate wars. Two years later Raymond managed to stave off a very determined Irish attack to regain the fortress and won the day when he led his garrison through the gates to fight the Irish beyond. Some measure of the Irish Army’s successes under their hero, Lord Castlehaven, came to 1645. Raymond had remained in charge and when Castlehaven threatened the castle, it fell into his hands without a shot being fired in anger against him. Thomas Raymond left Liscarroll and returned to England.

To be continued…

For more on North Cork history, check out Kieran’s and Dan Breen’s new book, North Cork Through Time (2015).

Captions:

832a. View of Liscarroll Castle, published in 1764, published as part of coat of arms of the Perceval family, Earls of Egmont (source: National Library of Ireland)

832a. Nineteenth century depiction of Liscarroll Castle by Robert O’Callaghan Newenham (source: Cork City Museum)

832c. View of southern gateway of Liscarroll Castle, present day (picture: Kieran McCarthy)