Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 30 July 2015

Cork Harbour Memories (Part 29)

Skeletons beneath our Feet

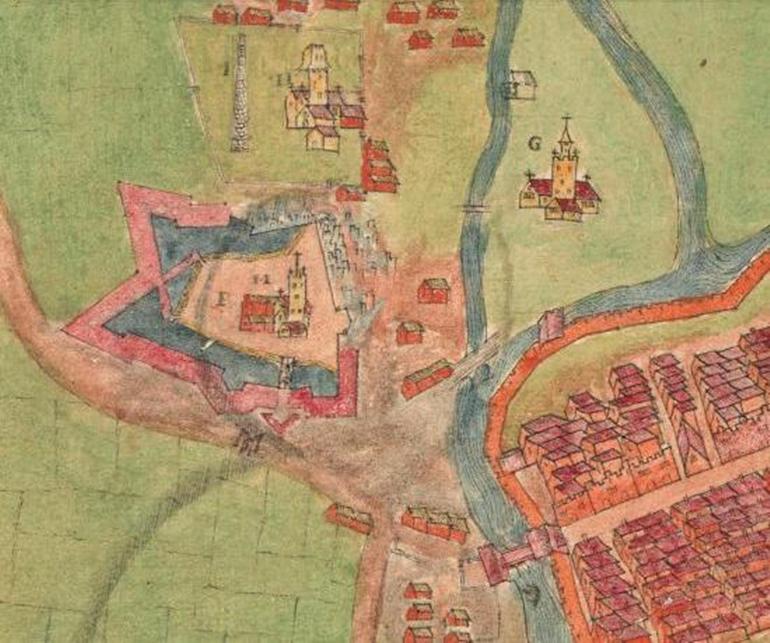

Previously, we discussed the Dominican Abbey at what is now Crosses Green. Exciting finds were unearthed in 1993 during the placing of foundations for the Crosses Green Apartment Complex. Excavated remains of buildings were discovered associated with the abbey especially the church, cloister or central walking area and other attached domestic buildings. Among these buildings, many medieval objects were found as well as one of the most preserved graveyards ever found in post medieval archaeological studies. All were studied under the watchful eye at the time of former City Archaeologist, Maurice Hurley and Cathy Sheehan (1995, see local studies in the City Library for their insightful excavation report)

Part of the finds included the remains of medieval pottery. Clare McCutcheon in her section in the excavation report noted that the largest assemblage came from the south-west of France from the Saintonge area and were early thirteenth to fourteenth century in date. In addition, native Cork type pottery was discovered as well as Redcliffe pottery from Bristol.

Nearly a half a dozen bone and antler artefacts turned up. These included a modified antler tine or an object used in some manufacturing or shaping process of bone or antler. A broken needle associated with medieval weaving was found along with what is described as a type of toggle to hold clothes together. Rosary beads or paternosters were found. Forty-two beads were, all bone in nature. The beads were found in relation with the torso of a skeleton in a grave.

Metal objects were discovered of which many were bronze in nature. These included several bronze pins, a needle, an ear spoon (from a toilet set or a surgical instrument set), a ring brooch, which would been used to fasten the cloaks of the monks, a buckle, the hand guard of a dagger, a tweezers, and an iron knife blade. Lead objects included nine lead rods, which were part of stylii or writing leads. Only one medieval coin of a medieval date was found, fourteenth to fifteenth century in date. One piece of structural timber was found, which was said to maybe part of a quay front revetment, a bridge, or a scaffolding piece used in the construction of the priory.

A total of two hundred graves were found. Under the careful excavation of Catyrn Power, the majority of the graves were discovered within the boundaries of buildings especially within the church and cloister area. Since, the abbey was built on a marshy island, there was a lack of acid in the underlining soil which resulted in little deterioration of the bones of skeletons found. All were reburied appropriately and safely. The majority were excellently preserved and therefore most of the graves comprised of intact comprehensible skeletons. Incidently the first graves associated with the Dominican Abbey are recorded as being located in 1804 when a Mr Walker unearthed several stone lined graves. He was building his own distillery at the time chose not to disturb the burials to any great extent.

Catyrn in her report notes three main types of graves discovered, which give an insight into the social structure around the area of the abbey. These types included shallow unlined graves which the majority of burials consisted of. In a few unlined graves, an unusual burial practice was noted. Small stones known as pillow stones or other skulls were placed on either side of the skull of the main skeleton in order to keep the skull itself from collapsing to one side.

The second type of grave found on the grounds of the Dominican Abbey was related to the evidence for charred coffins. In England, during the medieval period, charred coffins were utilised so that the decomposition of wood would be deterred. Stone-lined graves with slab capstones also made up a large part of the burials at Crosses Green. Associated with several of these type of graves on top of them were tomb slabs and effigies (carved statues in stone).

Three-quarters of the individual skeletons were found to be adults – the largest number being aged in their twenties There seemed to be slightly more males than females excavated. The mortality rate was found to be low and through present day research on medieval times, numerous reasons have for this have come to the forefront such as diet and living standards of the time. Poor living conditions in the nearby walled town and the abbey led to breeding grounds for rats and infectious diseases. In the town overcrowding was common in poorly ventilated dwellings with thatched roofs that had a clay floor which was an attraction to rats and fleas. The water supply was always subject to contamination from sewage and rubbish. Household waste was thrown onto the streets and laneways. Even dead animals were left to decay where they fell. Clothing and hair provided shelter from fleas and lice. Life was tough in medieval Cork.

In the case of the skeletons excavated and analysed at Crosses Green, just less than half were found to have degenerative joint disease or some form of arthritis. In several individual skeletons, nutritional deficiencies, tumours, dental diseases were noted along with infections. All these can be detected due to their changing effect on the shape and strength of the bone.

Check out Catyrn Power’s excellent blog, https://corkarchaeologist.wordpress.com/

To be continued…

Captions:

803a. Excavating skeletons at Crosses Green, 1993 (pictures: Catyrn Power, https://corkarchaeologist.wordpress.com)

803b. Excavating skeletons at Crosses Green, 1993 (pictures: Catyrn Power, https://corkarchaeologist.wordpress.com)