Ballinlough Over ’60s competition is back!

It is on Wednesday 18 February from 8pm.

The search is on for contestants.

Contact the chairperson of Ballinlough Community Association, Cllr Laura McGonigle, 0860829371 for more details.

Ballinlough Over ’60s competition is back!

It is on Wednesday 18 February from 8pm.

The search is on for contestants.

Contact the chairperson of Ballinlough Community Association, Cllr Laura McGonigle, 0860829371 for more details.

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article, Cork Independent

A Productive Process

When conflict broke out in 1854 with the Crimean War, followed by rebellions in India a succession of ensuing colonial conflicts and culminating in the Boer War of 1899 – 1902, Ballincollig Gunpowder Mills was an active and productive centre. It thrived because of war within and through the expansion of the British empire. It also flourished due to the business strategies and network of business partnerships the owners, the Tobins engaged with within the empire.

A newspaper article in the Cork Constitution in 1856 reveals many facets of the gunpowder production and illuminate the now ruinous mill structures that remain as symbols of the industrial process. The anonymous journalist remarks that in previous years to his report, new buildings had been added to keep pace with the advance of manufacturing science and the requirements of increasing demands and sale of gunpowder.

The journalist commented on the isolated and scattered position of the various portions of the works. Gunpowder he noted cannot, like other articles of commerce, be manufactured in one large area like at cotton or paper mills. Each process of the manufacture, from the first purification of the rough ingredients to the packing and storage of the finished article is conducted in a separate building, totally detached from the rest. The reason was influenced by the nature of the substances employed, which were liable at any time to ignite and blow up the walls and roofs of the various buildings in which they are contained.

The complex of Ballincollig Gunpowder Mills was therefore spread over 400 acres. Through diverting part of the River Lee an extensive canal was cut for the convenience of moving elements from one part of the works to another. The canal was over a mile and half long and in some places twenty metres wide. It was constructed at great expense and was considerably enlarged as the mills got busier.

The journalist writes of the canal continually enlivened by the passage to and fro of numbers in large boats. On these sulphur, saltpetre, charcoal and gunpowder in various stages of completion were transferred from one place to another as the processes of manufacturing required.

The ingredients in the composition of gunpowder were saltpetre, sulphur and charcoal mixed together in certain proportions. The journalist commented that it was in this context the experience of and judgements of the manufacturer were brought into operation. He had to determine the proportions in which the ingredients were to be combined according to the peculiar quality of gunpowder which he wished to produce.

Sulphur was an element which was used widely in various manufactures in the Ireland of 1856 and an enormous quantity of it was produced in the mining districts of Ireland. However, so great was the demand for sulphur in Ireland, an extra forty or fifty tons were annually imported from Sicily. The principal seat of the mining operations in Sicily was near Catolica. Sulphur there appeared in veins of various colours mixed with clay and gypsum. The general appearance is that of a shining red colour. Large patches of the sulphur stone were piled up over cauldrons sunk in the earth; a quantity of straw was then spread over the heap and ignited. The sulphur as it melted flowed down into the cauldron and was subsequently received into wooden moulds. The number of persons employed in Catolica in the extraction of ore and the exportation of sulphur was estimated at 8,000. Half of the entire quantity produced in Sicily was exported to Great Britain. For the manufacture of gunpowder the sulphur has to undergo a variety of processes of refinement and milling at Ballincollig to render it pure.

The saltpetre used in Ballincollig was imported from the East Indies. It was sent over in bags containing about 1 ¾ cwt, but was mixed with earths and salts for safety reasons. To remove these impurities the saltpetre at Ballincollig mills was melted in a large copper vessel. The solutions were then drawn off and crystalised. The crystals as removed from the crystallising-pans were again dissolved and subjected to the heat of a furnace by which the superfluous water of crystalisation was driven off and the remaining liquid being evaporated, the saltpetre is received into flat cakes shaped moulds. Thus prepared it possessed a white colour and was free from moisture. The product was then removed to the saltpetre mill and ground by a process similar to that for the grinding of sulphur. The residue of mainly salt was sold off.

The charcoal used in the manufacture of gunpowder was produced from alder, willow and hazel. The usual mode of manufacture was called ‘charring in pits’. It consisted of the wood being cut into lengths of about three feet with straw and then piled on the ground in a circular form and covered with straw, kept on by earth or sand to keep in the fire, giving it air by vent holes as was necessary. When the charcoal was completely made, which the men judged by the smoke and other appearances, the fire was quenched and the charcoal removed.

To be continued…

Captions:

526a. Ballincollig Regional Park, summer 2006 (pictures: Kieran McCarthy)

526b. ‘Frozen’, cog wheel mechanics for leaving water into the canal, Ballincollig Regional Park

It’s difficult at times to keep up the things you love. I am a lover of all things musical. Drama is one of my hobbies. Over the last decade, it has helped me to relax, have fun and get away from the pressures of being a writer. The Feis Matiu has been taking place in Cork since 1927. I have entered the open categories in musical theatre the last number of years with some success but with alot of learning outcomes. Below is an article the Evening Echo kindly published during this week. The main point that I was trying to make is that everyone should try out something new, push put the boundaries of oneself and touch base with hobbies you love. If that means standing on a stage and singing your heart out! well that’s way!

In the early nineteenth century, Ballincollig was one of three principal Royal Gunpowder Mills in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The other mills were at Waltham Abbey in Essex and Faversham in Kent. However, the mills at Ballincollig were constructed much later (1794) than the latter and hence the County Cork site was based on existing plans and technologies that had developed over many centuries.

Documentary evidence shows that gunpowder was produced in the Waltham Abbey area from at least the seventeenth century. Later the Waltham Abbey site became the leading English producer. The Faversham site was started as a private enterprise in 1653. In 1760 this site and a later site nearby were bought by the British Government. After the Napoleonic Wars the Westminster Government sold off all three Faversham sites. Without Faversham gunpowder, Britain’s industrial revolution could never have taken place. It was used to blast routes for canals and railways and to quarry stone needed for bridges and other structures.

In Ballincollig a high stone wall enclosed 431 acres across which were various structures of buildings in which the various ingredients of gunpowder were made or mixed. The end result was a volatile product used to advance the British Empire from blasting rocks in mines to aiming to kill people on Britain’s international battlefields.

Waltham Abbey, Faversham and Ballincollig gunpowder mills were serious production centres. They responded successfully in volume and quality to the massive increases in demand which arose over the period of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars from 1789, culminating in the English victory at Waterloo in Belgium in 1815. England’s war with France created an economic boom from many provisions regions like Cork benefitted from. In Cork Harbour the imperial navy established a large arsenal on Haulbowline Island and a naval dockyard was built. Martello towers were also erected in Cork Harbour offering the Navy protection. Ballincollig benefitted from large scale employment in the mills, investment in the regional roads infrastructure and the growth of the settlement of Ballincollig ensued.

In 1810, an army barracks was built in Ballincollig to protect the supply of gunpowder. The outer perimeter stone walls extended from the eastern gate of the mills to Inniscarra Bridge. Ballincollig Barracks was located to the northern side of the Main Street in Ballincollig town centre. In the years following the end of the Napoleonic Wars the mills entered a period of quiet with a steep decline in staff numbers and production levels.

In 1834, the Board of Ordnance sold the Gunpowder Mills to the Tobins, a Liverpool family. In the same year, Thomas Tobin married Catherine Ellis in 1835 and they moved into Charles Henry Leslie’s former house. Catherine was an avid painter so Thomas built an Oriel or a recess with a polygonal window built out from a wall. From this time on, the house became more affectionately known as Oriel House (now a hotel). The mills had lain derelict for 20 years before that.

By the year 1837, Samuel Lewis in his Topographical Dictionary of Ireland described Ballincollig as a place chiefly distinguished as a military depot. He highlighted the extensive gunpowder-mills, formerly carried on under the superintendence of Government. Lewis mentioned the purchase by the Tobins and the return to full operation of the mills. The army barracks contained accommodation for eighteen officers and 242 non-commissioned officers and privates. In the centre of the quadrangle, there were eight gun sheds and near them were the stables and offices. Within the walls was a large and commodious school room. The police depot for the province of Munster was situated here and the men were drilled till they were deemed ‘efficient’ and were then drafted off to the different stations in the province.

Samuel Lewis wrote about the artillery barracks forming an extensive quadrangular pile of buildings. In the eastern range were the officers’ apartments. On the western side stood a hospital and a neat church, built in 1814, in which service was regularly performed by a resident chaplain. There was also a Roman Catholic chapel. The buildings contained accommodation for 18 officers and 242 non-commissioned officers and privates. They were adapted to receive eight field batteries; though at the time of Lewis’ survey only one was stationed here, to which were attached 95 men and 44 horses. In the centre of the quadrangle eight gun sheds were placed in two parallel lines, and near them were the stables and offices. Within the walls a large and commodious school-room was also located.

Immediately adjoining the barracks and occupying a space of nearly four miles in extent were the gunpowder mills. At convenient distances were placed the different establishments for granulating and drying the gunpowder, making charcoal, refining sulphur and saltpetre, making casks and hoops and the various machinery connected with the works.

At a considerable distance from the mills were two ranges of comfortable cottages for a portion of the work-people, tenanted by 54 families, According to Samuel Lewis, the number of persons employed was about 200 and the quantity of gunpowder manufactured annually was about 16,000 barrels.

To be continued…

Captions:

525a. At the gates to Ballincollig Regional Park, winter 2006, on tour with Jenny Webb, local historian

525b. Ballincollig Regional Park, summer 2006 (pictures: Kieran McCarthy)

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Column,

Cork Independent, 28 January 2010

From the ridges at Scornagh, just west of Ballincollig, the view to the Inniscarra side of the Lee Valley is amazing. On the ordnance survey map of Scornagh, Bronze Age fulacht fia or cooking sites are shown. So I’m not the first to ‘feast’ on the view here; Prehistoric residents set up camp here and munched their boiled meat. But for me at this point I felt that I was giving one of my goodbyes to the rural Lee valley as I descended and headed into a busy Ballincollig.

Archaeological excavations on the Ballincollig Bypass in 2002 / 2003 uncovered habitations sites (houses and fulacht fia) from prehistory and the evidence for Ballincollig’s first settlers from 5,000 years ago. From Neolithic contexts, a house was excavated during the Bypass construction at Ballinaspig More (c.3,900-c.3,600 B.C.) as well as nearby ritual pit at Carrigrohane in which was discovered pottery, beaker pottery, flint fragments, charcoal and charred seed. From the late Neolithic and Bronze Age contexts, fifteen fulacht fia were excavated (c.2,500 B.C. in date). A Bronze Age to Late Bronze Age House (c.1,500 B.C.) excavated during Bypass construction at Ballinaspig More, Cremation pits were found at Barnagore (2,100 B.C.) and at Carrigrohane (c.1,500 B.C.). An Iron Age house was also excavated during bypass construction at Ballinaspig More (c.340 B.C.). From Early Medieval contexts, two conjoined enclosures were excavated during Bypass construction at Curaheen. A house foundation was discovered plus an enclosure as well as associated finds (dating to c.700 A.D.).

In the course of eight weeks during the spring of 2006 the excavation of a ringfort/enclosure at Carrigrohane, Ballincollig took place to make way for Cork County Council’s new Fire Department Headquarters located adjacent to the enclosure. The enclosure/ringfort inspired the architect to design the new headquarters, in keeping with the topic of the archaeological site. Most of the above land (1.99 acres) adjacent to the proposed location for the new Fire Department Headquarters was covered by a trivallate enclosure/ringfort. The monument was excavated by Dan Noonan Archaeological Services. The ditches and exterior were excavated exposing two deep ditches, exterior features in the form of post holed house and a tunnel.

A few years ago on a flight over the then undeveloped fields at Carrigrohane, Dr. Daphne Pochin Mould, a well-known and respected aerial photographer, pilot and archaeologist, who lives nearby, discovered the shape of the enclosure’s banks and ditches in the form of crop marks. Cork County Council’s Archaeologist, Catryn Power commented that the excavation of the ringfort through the promotion of our archaeological heritage is an integral part of the Council’s work. Archaeology was brought to life for the community at large.

Nearby is Ballincollig Castle, which was built in the early 1300s (A.D.) and was the castle of the Colls, an Anglo-Norman family. Hence the name Ballincollig or Baile an Chollaigh. The Castle was handed over to the Barrett family, a Norman clan in the barony of East Muskerry and after whom the barony, which contains Ballincollig is named. The Barretts had allegiances with local Irish families. The Castle was destroyed during 1641 and in 1689 it was garrisoned by troops of the Catholic King James II. In 1659, the manor of Ballincollig Castle was noted as eighteen inhabitants. Soon after, the Castle became unoccupied and became a ruinous structure until some renovations by the local landlord, Thomas Wise in the nineteenth century. Since then, the Castle has fallen into decay and remains a tourist opportunity waiting to be unlocked.

The interpretative panels in the Regional Park reveal that Ballincollig remained a small community till 1794 when Charles Henry Leslie, a leading Cork merchant established the local gunpowder mills, a unique industrial complex in southern Ireland. Shortly after, Oriel House was built by Leslie as his residence. Increased concern about the security of the gunpowder mills, coupled with the British government of the day’s policy for creating its own monopoly of gunpowder manufacture in these islands, greatly influenced the Board of Ordnance’s decision to buy out Leslie in 1805. In March 1805 the Board appointed its chief clerk of works for powder mills, Charles Wilkes, as superintendent of the Ballincollig gunpowder mills. Wilkes began by improving access to the complex from the old Killarney road to the north, by entirely rebuilding Inniscarra Bridge replacing the six arched (original date of construction unknown) with twelve semi circular arches. The area of the barracks and mills, including administration buildings, a network of canals and the new cavalry barracks, were all greatly expanded in the period 1806-15.

To be continued…

Captions:

524a. View of Inniscarra Reservoir, southern side, near Scornagh (pictures: Kieran McCarthy)

524b. Ballincollig Castle from near Greenfields, Ovens

Kieran’s Motions and Question, Cork City Council meeting, 25 January 2010

Motions:

That the City Council replace the relevant rotting timber frames of doors in Douglas Swimming Pool (Cllr K. McCarthy)

That P.R. literature on the City Council’s educational bodies such as the Lifetime Lab and Blackrock Castle and any other relevant funded bodies be placed on a table in the foyer of the new extension of City Hall for customers to peruse (Cllr. K McCarthy)

Question to City Manager:

That the City Manager would comment on the City Council’s policy on businesses and organisations breaking litter laws by erecting illegal signs on grass verges, poles etc around the city. How many businesses and organisations have been fined in 2008 & 2009? How many were fined for illegal signs in the south east ward? (Cllr Kieran McCarthy).

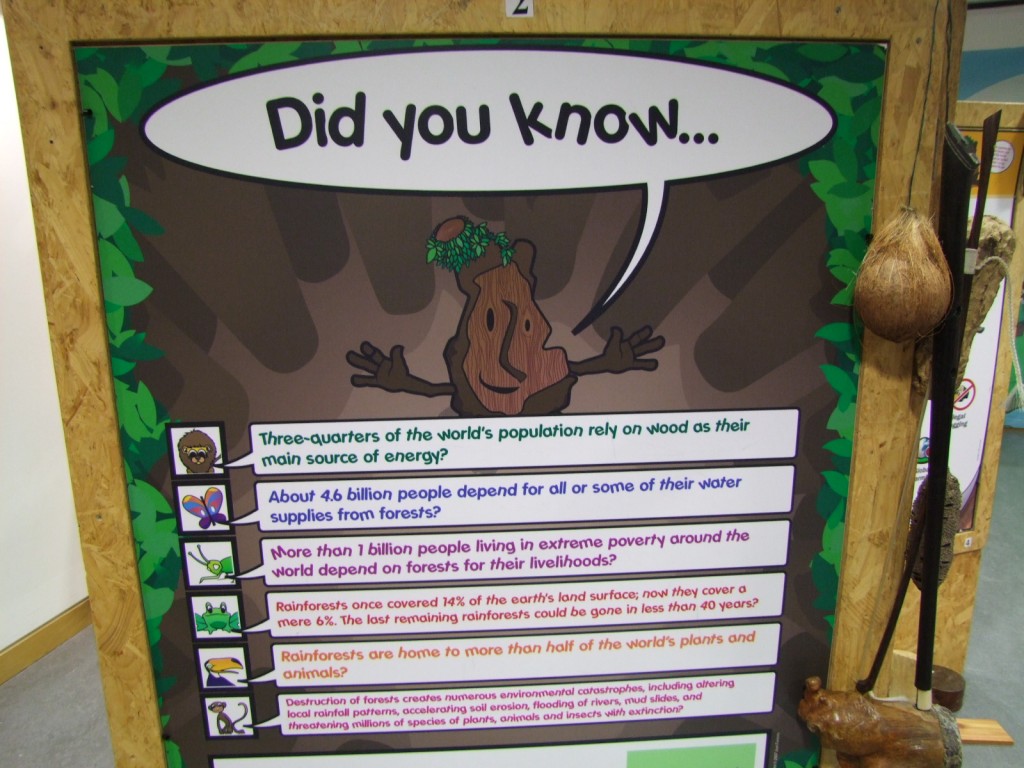

An exhibition on deforestation in the world and climate change has opened in Bishopstown Library. It’s worth a look. Below are some pictures of the panels.

Last Thursday, I had the pleasure of reading in Jury’s Hotel on the western Road. A number of Cork figures selected their favourite gems from Tom FitzGerald’s wonderfully entertaining and informative story of Cork. Others included Poet Gerry Murphy, Cork City Librarian Liam Ronayne, Irish Examiner’s Marc O’Sullivan and Cork Evening Echo Editor Maurice Gubbins. RTE’s Aidan Stanley was the MC for the evening.

Last Thursday, I had the pleasure of reading in Jury’s Hotel on the western Road. A number of Cork figures selected their favourite gems from Tom FitzGerald’s wonderfully entertaining and informative story of Cork. Others included Poet Gerry Murphy, Cork City Librarian Liam Ronayne, Irish Examiner’s Marc O’Sullivan and Cork Evening Echo Editor Maurice Gubbins. RTE’s Aidan Stanley was the MC for the evening.

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Column,

Cork Independent, 21 January 2010

Delights and Inspires

So there are many meanings that one can gleam from churches such as St John the Baptist – in particular there are meanings within elements such as its architecture and memorials. I also read in Fr James Tobin’s history of Ovens (1985), that when the Church was built there was very little seating accommodation. It was later made by Con Sheehan of Ovens at the cost of £1 each. The stained glass windows were presented by the Murphy family of Brownhill who later emigrated to Boston. The tabernacle was donated by a Mrs Aherne, the cross over the tabernacle by James Reid and the organ by Mrs P.J. O’Connell.

There is a very deep religious component in the history of Ovens Parish. What I find appealing are the links from the nineteenth century structures such as St John the Baptist backwards into penal times and how people practiced their beliefs in all sorts of structures from ruinous non-roofed buildings to holy wells. With that in mind, the present day Church of the Immaculate Conception in Farran is also worth a look especially as it has a remarkable stained glass window of St Finbarre.

About the beginning of the nineteenth century a church was built beside the road leading from Farran Village to Aglish burial ground. Though the walls were demolished after building the present church, the old entrance gate and pillars remain to mark the spot where it stood. The old church was one of the first churches opened after the relaxation of the penal laws and nearly thirty years before Catholic Emancipation. Local knowledge recorded that it leaned against the side of a hill and was covered with a roof of thatch.

The present church was built during the pastorate of Canon Maurice Walsh, but it is more closely associated with the name of his curate, Fr. John Cotter, who afterwards became Archdeacon. It was dedicated to Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception. The Immaculate Conception was solemnly defined as a dogma by Pope Pius IX in his constitution on 8 December 1854. For the Roman Catholic Church the dogma of the Immaculate Conception gained additional significance from the reputed apparitions of Our Lady of Lourdes in 1858. At Lourdes a 14-year-old girl, Bernadette Soubirous, claimed that a beautiful woman appeared to her that of Mary. So in sense, through its name, Farran Church became one of a series of beacons that advocated for a renewed Roman Catholic tradition for a well-established philosophy for the study of the Immaculate Conception and the veneration of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

The church was solemnly consecrated on Monday 19 August 1860 by Rev. Dr. Leahy, Bishop of Dromore. Consecration makes the walls of the church as sacred as the altar. Gold coloured crosses within a circle are the marks of consecration, as distinct from the ordinary ceremonial of a dedication or blessing of a church. These crosses could be seen on the side walls of the church until 1968 when they were taken down because of renovations.

The church was erected for the sum of £2,000. It was only later after 1860 that seating accommodation was provided by the people of Fergus on the northern side of Inniscarra Reservoir. A simple elegant design was proposed especially as those contributing were recovering from the aftermath of the Great Famine. The design of early Gothic was by Messrs. Hadfield and Goldie of Sheffield. Matthew Ellison Hadfield (1812 – 1885) was an English architect of the Victorian Gothic revival Gothic church echoing medieval English and French models and was inspired by the work of Augustus Welby Pugin. Gothic Revival at that time succeeded in becoming an increasingly familiar style of architecture connected with the notion of high church superiority, as promoted by Pugin.

Matthew Ellison Hadfield is chiefly known for his work on Roman Catholic churches, including the cathedral churches of Salford and Sheffield in the UK. Practicing as an architect in Sheffield from 1834, Hadfield’s first commission was the design of a monument to the 402 victims in Sheffield of the cholera epidemic of 1832. In 1838 Hadfield entered a partnership in Sheffield with John Grey Weightman, which lasted until 1858. In 1850 they were joined by their former pupil George Goldie, and the partnership between Hadfield and Goldie lasted until 1860. Indeed Farran Church was one of the last church designed by the partnership. Another noted Irish commission was the design of the Cathedral of the Annunciation and St. Nathy, Ballaghaderreen, a town in Co. Roscommon in 1855. Hadfield’s practice is still trading at Hadfield Cawkwell Davidson Ltd in Sheffield.

The acre and a half for the Farran Church was given by Mr William Clarke of Farran, who was a Protestant, in exchange for the church, which was demolished in 1860. Clarke, who had his own Tobacco Company, took an interest in the Farran landscape. When the leases of the local farmers had expired he compensated them and bought about 1,100 acres of land. Years later the land was divided again by the land commission between about 30 small holders, but about 200 acres were retained by the Clarkes.

To be continued…

Captions:

523a. Church of the Immaculate Conception, Farran, co. Cork (pictures: Kieran McCarthy)

523b. Part of the stained glass window of St Finbarre in Church of the Immaculate Conception

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Column,

Cork Independent, 14 January 2010

Words of Stone

St John the Baptist in Ovens is not the first church that I have wandered up during the off peak mid afternoon silence in such buildings. I tend to search for clues, memories, looking for plaques and searching for stained glass windows of St Finbarre and his memory in the River Lee valley’s churches. I seem to continue to train my eye in looking for the smaller details of the human experience in the Irish landscape.

According to Samuel Lewis’s Topographical Dictionary of Ireland (1840s), St John the Baptist Church, Ovens was built in 1835. He described it as ‘handsome’ edifice of hewn limestone in the mixed Gothic and Grecian styles of architecture with well lit tall round headed windows. Its plan is typical of other church structures of its day. Indeed, in the wider context, in 1829 the Catholic Emancipation Act gave much more freedom to Catholics and that strengthened the composition of the church. Hence, new churches such as Ovens were built in Ireland to cope with the expanding congregations. However, these new churches soon became symbols or markers of religious and political change within their respective area and era of origin.

Local history work by Fr. James Tobin in the 1970s, a curate of Ovens, wrote that the church of St John the Baptist became the parish church of the Union of Ovens. In addition, records reveal that in the sacristy of the church at one time was a library of ancient tomes or stones but that history is now lost. There was a school also on the site. It was replaced in 1939 by a new building across the road.

Examining the structure reveals more insights into the ideas that brought it into being. In the architecture itself, the human story of harnessing the Irish landscape is told. I think it was the imposing limestone of St John the Baptist Church that first struck my attention. The district of Ovens, as noted in previous articles, was once known for its caves and mysterious caverns beneath the ground. From this landscape the rock was broken up, taken up and re-imagined as a type of sacred place by the local priest and architect. The excavated stone was carved as blocks for the new church by stone masons but interestingly its foundations still cling to the bedrock from which it comes from. The exterior and interior beauty and aesthetics of church depended on contemporary technology, politics and money. The architect is also entrusted to map a religious journey for the pilgrim. The finished product reveals the talent and ambition of the architect and the community involved in constructing it. Both translated imagined ideas into something physical and something poetic through iconography.

I sat in one of the pews in St. John the Baptist, the light streaming through a stained glass window of the ‘Lamb of God’. At the base is inscribed the name Daniel Walter Murphy, born Muloughroe RIP, 1823 and his Mary A. Bowen, his wife, born Passage, Cork 1823, RIP. A second stained glass window of Mary, Mother of Christ, is inscribed William Bowen Murphy, born Mullaghroe, died Boston. USA, RIP, The inscriptions do not say anymore but do invite the viewer to remember the patron. Through my actions, I perform what the memorial wants me to do. Memorials such as these tend to indirectly highlight the remembered in a high social standing stressing their personal qualities, goodness and piety.

I remember several years ago cutting out an image in the local newspaper of the crucifixion scene in the stained glass windows of Our Lady of Lourdes, Church in Ballinlough, Cork City and remarking on its power to set the imagination running and in recent years marvelling at the dove scene, the Holy Spirit in the choir area of the North Cathedral. Both are pure artistic genius. Standing in St John the Baptist, looking at the stained glass windows, I note in my notebook that even the past was a colourful and imaginative place, where remembering someone or an event was something to cherish. Every place also tends to have a memory, which emanates through some memorial revealing the human experience with its range of emotions – sadness, love that someone wished to record. Every place seems to have a story to tell of survival, struggle and transformation.

Many Irish churches tend to be visited for their sanctity more so for their art and architecture. However, all have an enormous array of expressive meanings waiting to be unlocked. These meanings depend on the viewer’s background, interest and expertise. St. John’s the Baptist has a sense of form, space, light and shade, solidity and weight. The interior, which was revamped in recent times, is built to welcome. It is a monument in its day and seems to give order to that world on reflection and to the present. However, I have to say for me, churches like St. John the Baptist are treasure troves of ideas about the importance of human ideas and how they transform and mark the chaotic world around us.

To be continued…

Captions:

522a. Stained glass window at St John the Baptist Church, Ovens (pictures: Kieran McCarthy)

522b. Exterior of St John the Baptist Church, Ovens