Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 4 December 2014

Cork Harbour Memories (Part 2) – The Wreckage of the Past

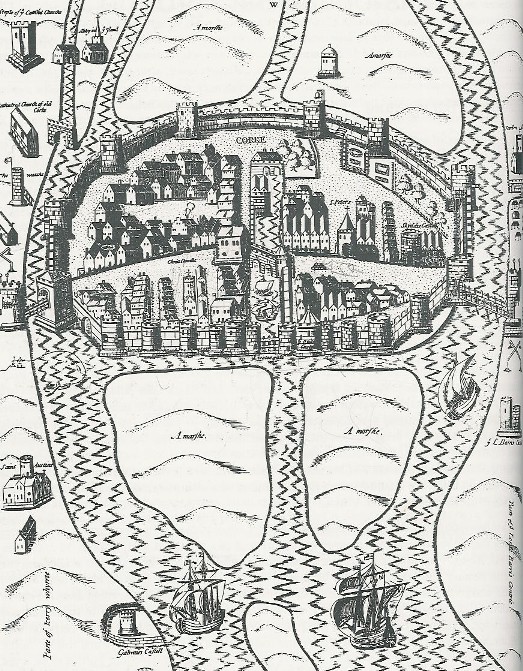

The amount of boats that have plied Cork Harbour is immeasurable. The large volume of extant admiralty charts from different periods of time point to negotiation around rocks, shallows and islands, and show carved out navigation routes. Whereas today, every metre of the harbour is mapped, what about those who rowed around it thousands of years ago exploring its corners and niches, hunting and fishing, and where the stars and landmarks were their mental maps.

The names of two islands, Haulbowline and Foaty Island, hark back nearly a thousand years to the first know group of sailors – the Vikings and their ancestors, who harnessed the harbour for survival. The name Haulbowline may come from the Old Norse áll-boeli meaning an ‘eel dwelling’ whilst Foaty may comes from the Irish fód te, meaning ‘warm soil’; it could also comes from Old Norse fótey, meaning ‘foot island’, maybe referring to its location near the end of the river.

The recent publication Archaeological Excavations at South Main Street 2003-2005, edited by Ciara Brett and Maurice Hurley, brings the reader back to a time where the natural environment of forests, the River Lee’s estuarine silt and the sheltered harbour were explored and mined for their resources. It is the eighth carefully researched and thought provoking book on the archaeology and history of Cork to be published by Cork City Council. This publication outlines the results of two large-scale excavations which took place at 36-39 and 40-48 South Main Street. Both sites are located in close proximity to the South Gate Bridge, one of the main entrances to the medieval walled town of Cork. The results of the excavations are significant as they have added to our knowledge of the formation and development of the City.

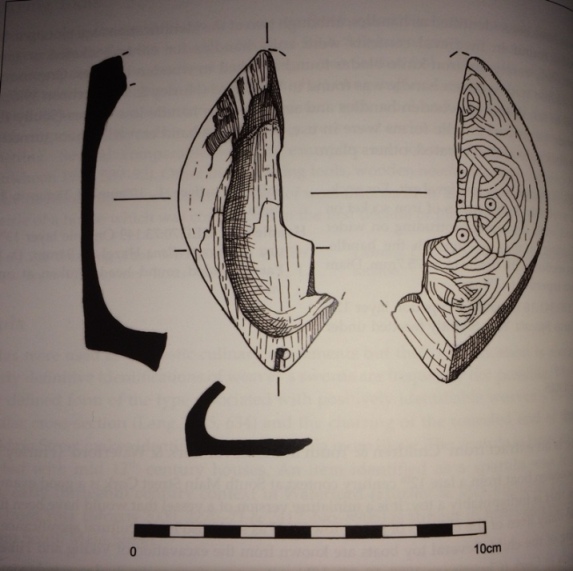

There are many fantastic revelations in this book about reclamation from the swamp to outlining in detail the material culture from pottery to the use of wood for housing to gaming pieces. The excavations were undertaken by Sheila Lane and Associates and the Department of Archaeology, UCC. Cork City Council. The various contributors work hard to paint a picture of their respective sites across several centuries. In particular in this book they place a large focus on Cork in the early twelfth century, a period before the Anglo-Norman invasion. By that time, the Hiberno-Norse, those living in Ireland with a Norse ethnic background, were rooted and settled in places such as Cork, Waterford, Wexford, Limerick and Dublin. Indeed, in all the latter places, excavations have taken place and the role of the Hiberno-Norse society debated in books and articles. The role of their early ancestors in piracy is much portrayed in the nation state’s Irish history books but their role in creating early towns not as much. The general collective memory within Cork’s history has, over several centuries, reduced them to the date of the first attack on Cork’s monastery (820AD) and an almost passing nod to the fact that they built a settlement on a swamp. The new book by Ciara and Maurice continues the pursuit of putting the Vikings on the academic history map and also implanting them into the popular imagination of Cork’s past – the latter perhaps being a harder task when it comes to changing the present day collective memory of a city.

For whatever reason, the people of Cork, through several centuries, chose to forget the Vikings, their history and ultimately their legacy. For all intensive purposes, the excavated South Main Street sites and everything found from the twelfth century, belongs to the wrecking ball of time and to the wreckage of forgetting. On troweling back the earth, the archaeologists pealed back different temporal contexts. Two to three metres underneath our present day city, they exposed the remains of timber structures lingering, intrusive and protruding through the mud – these were ruinous, abandoned, broken, segmented, mixed up, rotting, crumbling, and aged on the edge of a swamp. The timbers were the sinking roots, cultural products and ideas of a long lost settlement – an enigmatic space where no written documentation existed for bar the variations in the rings of the timbers. The rings alluded to growth and resilience, an age before use and being part of a woodland at one stage in their life. Despite their decaying image, the intensity of construction and some details in the skilled carpentry work remained for all to see.

At this crossroads of time, according to expert David Brown (p.525 in the book) there is an indication from the dendrochronological dates of the timbers found on the site that there was a continuous felling of trees and construction of buildings and reclamation structures from just a few years before 1100AD to 1160AD. So here on a swamp 900 years ago, a group of settlers decided to make a real go at planning, building, reconstructing and maintaining a mini town of wood on a sinking reed ridden and wet riverine and tidal space. One has to admire their intent, vision, tenacity and of course their legacy is the eventual reclamation of other marshy islands and the creation of the city of Cork.

The publication Archaeological Excavations at South Main Street 2003-2005 is available directly from the City Archaeologist Ciara Brett (ciara_brett@corkcity.ie, 021-4924705) and is also available in Liam Ruiseal Bookshop, Cork and Waterstones Bookshop, Cork.

More on this next week…

Captions:

771a. Archaeologists from Sheila Lane & Associates digging at the Grand Parade City Car Park 2004; in the picture from the top right, South Gate Bridge Debtor’s Gaol (c.1713), thirteenth century town wall (centre), thirteenth century house foundations (right of centre), and twelfth century revetments (bottom right) [picture: Kieran McCarthy, 2004]