Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 17 March 2016

Cork Harbour Memories (Part 53)

Cessations, Confederates and Crown Supporters

During the Confederate wars of the 1640s, one leading crown supporter in Munster was the prominent military commander and fifth Lord Inchiquin, Murrough O’ Brien. He ruthlessly kept control of south-western Ireland until the Cessation of Arms was signed between the Confederates and the King’s representative, the Marquis of Ormond, in September 1643. Then Inchiquin’s concerns began over his future as lord in the province and he defected to the side of the anti-crown supporters or the anti-royalist side. The religious policies of Charles I, united with his marriage to a Roman Catholic, produced the antipathy and mistrust of reformed groups such as the Puritans and Calvinists, who perceived his views too Catholic.

Inchiquin was civil and military governor of Munster and held command by royal and parliamentary commissions but was highly ambitious. After his father-in-law, Sir William St Ledger, who held the presidential office in Munster died, he thought that he would receive the title. During the Cessation of Arms, Inchiquin sent five Irish regiments to reinforce the King’s army in England in the expectation that he would be granted the presidency of Munster. However, the position was left vacant and Inchiquin only became the acting president for several months. When it came to the securing of the post of President of Munster in February 1644 in Oxford with Charles I, he failed to acquire it.

Inchiquin also had a fear of losing his land. When in September 1643, a truce regarding the hostilities between the crown, Charles I and the Irish Confederates was drawn up, Inchiquin and his companions were not too pleased. During the war with the Irish Catholics, finance for the English crown’s armies in Ireland was achieved through contributions from several baronies and towns and also through the raiding of monies belonging to Irish Catholics. However during the cessation of hostilities, commanders like Inchiquin were not willing to take the full burden of the expenses. He worried that through lack of finance his army would have to be disbanded and that towns and garrisons would return to Irish possession. Subsequently Inchiquin defected to the side of Parliament or to the growing anti-crown or anti-royalist side. To parliament he argued that his defection was due to the undermining plans for the English crown by the Irish Catholics. He demonstrated this by expelling hundreds of Irish people from their homes in Cork, Kinsale and Youghal in July 1644.

The civil war in England between anti-crown Protestants and Charles Is’ supporters escalated quickly. Inchiquin after his defection received his title of President of Munster and used his position to upset the King’s peace covenant, primarily conducted by the King’s Lord Lieutenant in Ireland, Ormond. Inchiquin introduced a new oath which would maintain and defend the Protestant religion. Inchiquin remained on the defensive against the Confederates.

Twelve months after the expulsion of the Irish, Inchiquin realised that parliament had no intention of sending soldiers to Munster and were content with the peace treaty in place. He appealed on the grounds of political and religious reasons but his undermining of Parliamentary power was clear and culminated in several Munster Parliamentarians calling for him to be impeached before the Commons in England. However, these claims were dismissed due to the Commons’ own problems with the parliament and king.

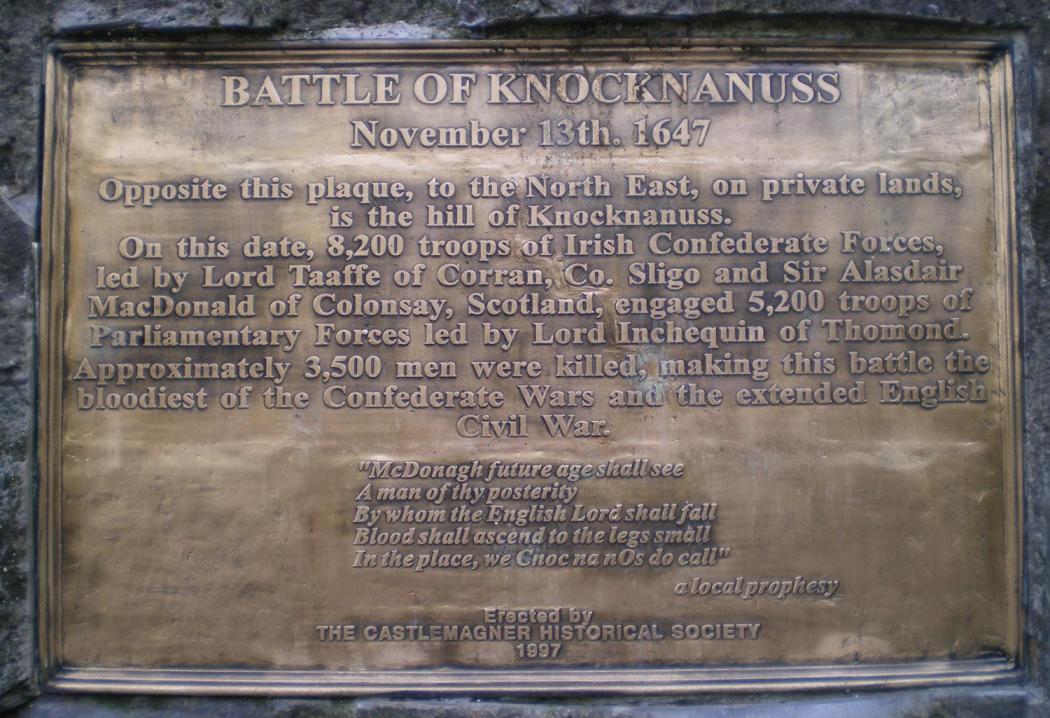

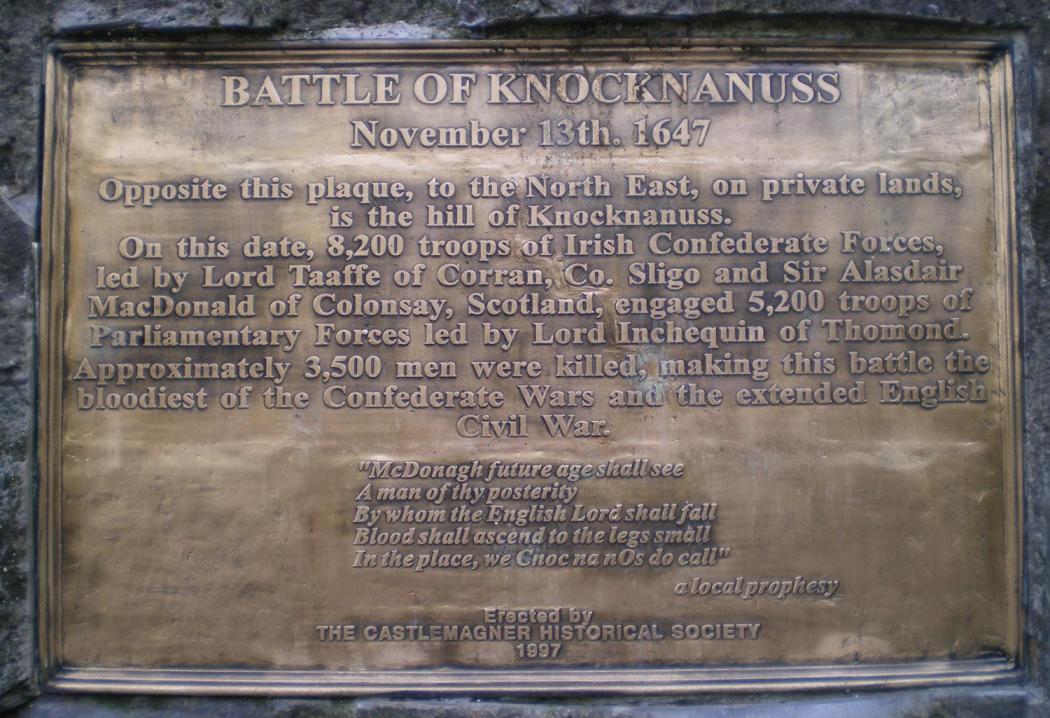

During the summer and autumn of 1647, Inchiquin decided to assert his authority in Munster by mounting a major military offensive against the Confederates. He stormed and captured Dungarvan, Cappoquin and other garrisons. In the post cessation of arms period, the Confederates sent Viscount Taaffe of Corran, Co. Sligo and Sir Alasdair MacDonald of Colonsay, Scotland into County Cork with 8,200 troops. Although heavily outnumbered, Inchiquin with his 5,200 troops inflicted a decisive defeat on the confederates at the battle of Knocknanuss four miles east of Kanturk in November 1647. Approximately 3,500 men were killed, making the battle the bloodiest of the Confederate and the extended English Civil War. Inchiquin won, was praised by parliament but afterwards, it was discovered that there were several allegations made against Inchiquin concerning the fact that he had enlisted royalist soldiers and gave high positions in his army to ill fit men. He denied the allegations, escaped impeachment again. He still requested more soldiers to come to Munster to suppress the Irish.

Inchiquin’s fear of the Irish retaking the land nearly became reality after Knocknanuss when royalist forces secretly blocked forces and supplies to Munster. As a result, parliamentary commissioners were sent to Munster, what Inchiquin had demanded since his first day as President of Munster. Unfortunately, by the time the Commissioners, arrived in Munster, Inchiquin had amassed a small army with his own loyal officers to deal with his fear of the Irish confederates himself. The Parliamentary Commissioners were called back to England and Inchiquin was declared a traitor and all honours bestowed on him were taken away.

On 30 January 1649, the parliament in England arranged the beheading of Charles I and plans were made to restore the throne to parliament itself through the proclamation of a new king, Charles II. To suppress any royalist support in Ireland, a new army was established under the leadership of the new Lord Lieutenant in Ireland, Oliver Cromwell.

To be continued…

Captions:

835a. Historical plaque marking the site of the Battle of Knocknanuss 1647 (source: Cork City Library)

835b. Historical plaque marking the site of the Battle of Knocknanuss 1647 (source: Cork City Library)