Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 25 August 2022

Journeys to a Free State: The Death of Michael Collins

Just over a week after reclaiming Cork City for the Irish Provisional Government, General Emmet Dalton played host to National Army Commander in Chief Michael Collins. On Sunday, 20 August 1922, Michael arrived from Dublin with his convoy to begin checking out the Republican manoeuvres in West Cork.

Dalton later recalled that he advised Collins that being in Cork was an ‘unnecessary risk’. Collins responded, “Nobody will shoot me in my own county”. Two days later, Dalton was travelling with Collins in his touring car in West Cork when their convoy was ambushed at Béal na Bláth some short few miles from Bandon.

It was on 22 August at about 7.15pm-7.30pm when the convoy consisting of a motorcycle outrider, a touring car, a Crossley tender and an armoured car were halted by a barricade on a bend in the road. Michael and his convoy took shelter on the side of the road.

In a very insightful section on an RTE documentary in 1978, entitled Emmet Dalton Remembers, it covers the life and times of the Major General. It was first broadcast following his death in March 1978. It was made in the final eighteenth months of his life. The programme is currently posted on YouTube. Dalton at eighty years of age is interviewed at Béal na Bláth.

Dalton recalls that once the ambush started that he and Collins got out and some fellow soldiers got off the Crossley tender and they hid behind a small ditch. It gave them cover from the angle from which the firing was coming, which was up from around 200 yards.

Dalton recalls: “From the volume that was there I would say that there were but a half a dozen at the most – firing rifles. A chosen ambush position is always perilous, and this was obviously a very bad position. There was no area for retreat. There was only one thing that we could have done was drive on. which I said to the Commander in Chief – ‘drive like hell’ but he elected to stop here and fight them, so we did…We were stretched out. We wouldn’t have been piled on top of each other…The spot where we were was one continuous bend of bank and the other members sheltered were firing obliquely across”.

Dalton relates that he saw action and indications of rifle fire. There were 15 to 20 minutes maximum of action on both sides. The motorcyclist came back and said that the obstruction had been cleared. So that it was then possible for them to have driven on. With one eye on Collins and after ten minutes of engagement. Dalton witnessed Collins getting up and moving to the back of the armoured car. He used it as protection to have a better sight of what was happening on the hill above. Then he moved from there up around the bend out of Dalton’s vision but he was firing from up ahead.

Dalton recalls that he thought he heard some of his convoy calling him; “I jumped up on at that stage O’Connell had been up the road to me and he said where’s the Big Fella so I said he’s around the corner around the bend. We both went up there and he had been shot. He was lying there with a very gaping wound to the back of his head…So I called the armoured car back and we lifted him and took him unto the side of the armoured car, we moved behind the armoured car with the armoured car between us and their firing position. We got him to the position on the side of the road. Under protection of the armoured car, I bandaged the wound and O’Connell said an act of contrition to him. I knew he was dying, if not already dead, so we did the best we could to cover it up [the wound].

All action at this stage practically had stopped. Except while they were lifting the body onto the armoured car, the motorcycle scout lieutenant Smith had come forward to give his help. In doing so there was an odd shot came and he was shot through the neck. It was a clean wound and he carried on helping them.

Collins’ wound was a very large wound open wound in the back of the head. On the wound Dalton recalls; “It was difficult for me to get a first aid field bandage to cover it. When I was binding it up – it was quite obvious to me – with the experience I had – it was a ricochet bullet. It could only have been a ricochet or a dum-dum. there was no exit wound…I felt he was dying or dead by the time I reached him. We were both very upset as you can well understand emotionally, and the rest of the word got around to the rest of our column. We got them together and moved quietly down the road and we moved Collins’ body from the armoured car situation onto the touring car back”.

Dalton sat in and carried Collin’s weight on his shoulder in the car and they drove off back to towards their home base of Cork. He remembers a tough journey back to Cork City. “It was a troublesome journey; we had encountered a lot of trouble and bother on the way because the roads were blocked. We had at one stage to go through a farmyard and came out on the other side. It took us quite a long time because we didn’t reach Cork City on 12 midnight”. To this day, there is no consensus as to who fired the fatal shot.

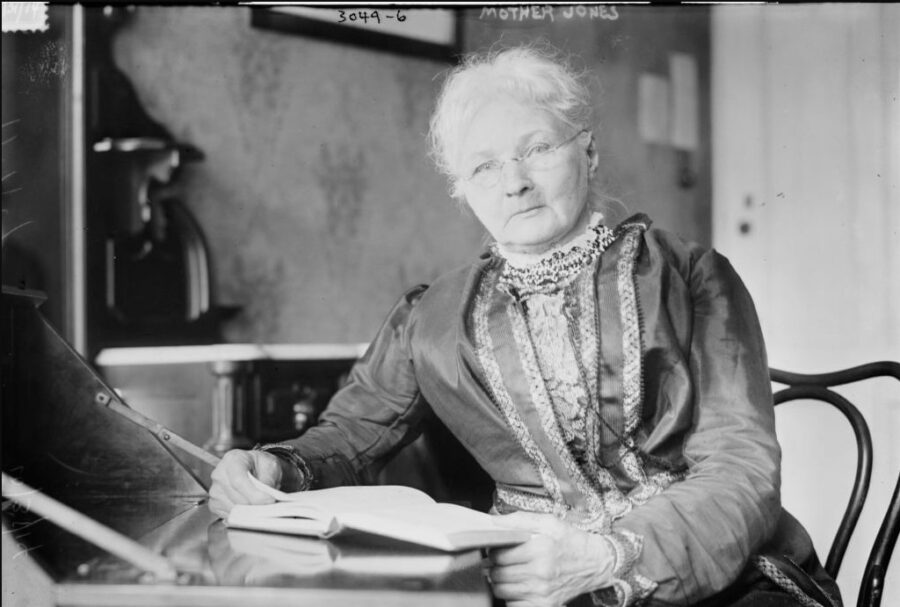

Caption:

1165a. Memorial at Béal na Bláth, County Cork, present day (picture: Kieran McCarthy).