Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 3 March 2016

Cork Harbour Memories (Part 51)

Confederate Bloodbaths

At the Battle of Liscarroll in September 1642, over 600 confederate Irish Catholics were killed including a high proportion of officers (see last week). The local Catholic gentry were decimated by the battle. The Fitzgerald family of the house of Desmond lost 18 members. English commander Lord Inchiquin executed 50 officers whom he had taken prisoner, hanging them subsequently.

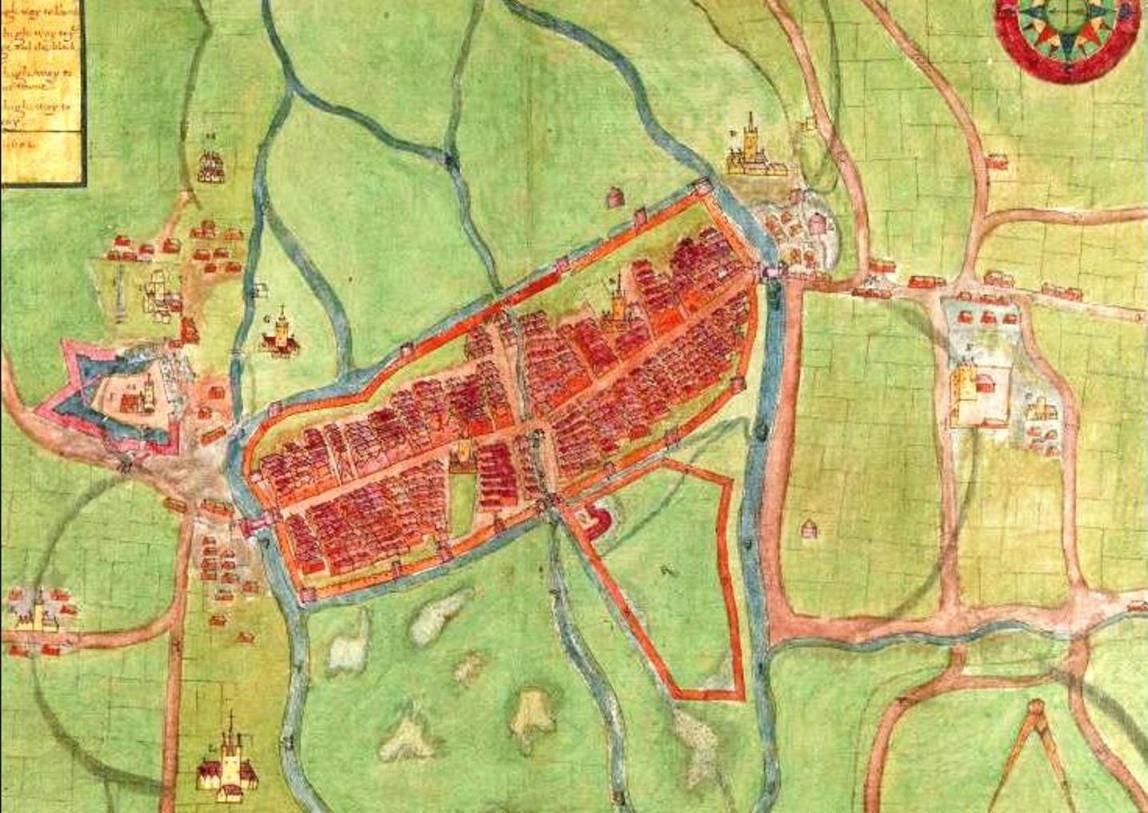

It is difficult to research and unravel many of the local histories across County Cork from this era. I draw below from several local historical works. Earlier in the year of 1642 on 11 February, the confederate forces under Lord Mountgarret entered Mallow. On this occasion Captain Jephson entrusted the strong castle of Mallow to the custody of Arthur Bettesworth. Arthur possessed a garrison of 200 men and an abundant supply of arms and ammunition, and three pieces of ordnance. Mallow’s Short Castle was defended by Lieutenant Richard Williamson. After sustaining repeated assaults, he lost most of his men. Several breaches were made and he agreed to surrender upon terms. After he left the fortress, Lieutenant Williamson with the rest of his party fought his way through the confederate ranks and retired into Mallow Castle. The confederates, during their nearby stay, chose as their commander Garret Barry and he and a party of soldiers attacked the fortified mansion of Mr Clayton, in the immediate vicinity. Two hundred lay dead by the time they took the house. Mallow Castle was assaulted and taken by the confederate military commander, James Touchet, Earl of Castlehaven (in West Cork), in 1645.

In other areas of North Cork surrounding places such as what is now present day Mitchelstown were also under pressure by confederate advances. Back over 400 years ago it formed part of the extensive possessions of the Clongibbon family. The so called White Knight of Clongibbon was descended by a second marriage from John Fitzgerald, ancestor of the illustrious houses of Kildare and Desmond. The Clongibbons had a castle in what is now Mitchelstown, which was reduced by the confederates in 1641. It was consequently retaken by the English, and was afterwards besieged by the Earl of Castlehaven, to whom it was surrendered to in 1645. Margaret Fitzgerald, who was sole heiress of the Clongibbon White Knight, married Sir William Fenton, and their only daughter conveyed this portion of the estates by marriage to Sir John King, who was created Baron Kingston by Charles II, in 1660. Hence the Kingston line began in the region.

Battles such as Liscarroll and at places such as Mallow and Mitchelstown meant North Cork would be an English Protestant stronghold for the rest of the confederate war. After the battle most of the lands in north Munster were granted to English settlers in return for cash. The monies were used by the parliamentarian army to fund their activities in the English civil war. Much of the land was returned to the original owners after the restoration of Charles II to the throne of England during the 1660s.

Lewis Boyle, second son of Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork, was killed at the Battle of Liscarroll. Aged twenty-three, his peerage, Viscount Boyle of Kinalmeaky, was succeeded by his elder brother Richard, who the following year also succeeded his father as second Earl of Cork. Lewis played a part in suppressing rebellions in West Cork in the year leading up to the North Cork battles. At the commencement of the confederate war in 1641, Bandontown was placed under the government of Lewis Boyle, Lord Kinalmeaky, who took possession of it in January 1642. He mustered all the inhabitants to put it into a state of defence. As it was the only walled town in this part of the country, it became an asylum for the English of the surrounding district. By its own resources it maintained four companies of foot, raised a corps of volunteers, and made preparations both for offensive and defensive warfare.

On 18 February 1641 a party of Irish under McCarty Reagh approached. Lord Kinalmeaky sent out 200 foot and 60 horse and a severe conflict ensued and several were killed. In a short time they took several ringforts in the adjacent territory which had been held by the Irish. The impressive castle of Downdaniel, at the confluence of the Brinny and Bandon rivers, built by Barry Óg in 1476, and the castle of Carriganass, built by the McCarthys, were both besieged and taken by the garrison of Bandon.

On the breaking out of the war in 1641, the English settlers in Clonakilty were compelled to flee for refuge to Bandon. In the following year, Alexander Forbes, 10th Lord Forbes (of Aberdeenshire) with his English regiment from Kinsale and some companies from Bandon, arrived here. He left two companies of Scottish troops and one of the Bandon companies to secure the place till his return, and proceeded on his expedition towards the west. This force was, soon after his departure, attacked by multitudes on all sides. The Scottish troops refusing to retreat were cut to pieces. The Bandon company defended themselves in an old ringfort on the road to Ross, till a reinforcement came to their relief. United they attacked the confederates, and forced them into the island of Inchidoney, when, the tide coming in, upwards of 600 of them were drowned. The troops then returned to Bandon.

To be continued…

Captions:

833a. Mallow Castle, c.1900 (source: Cork City Museum)

833b. Carriganass Castle, Keimaneigh (picture: Kieran McCarthy)

833c. Summer sunny days at Inchidoney beach, West Cork (picture: Kieran McCarthy)