Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 22 March 2018

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 22 March 2018

Stories from 1918: Tales from the Victoria Hospital

This week, one hundred years ago, Cork Church of Ireland Bishop Charles Dowse presided at the annual general meeting of the Victoria Hospital, which was held at the institution. The Victoria Hospital was originally founded as “The County and City of Cork Hospital for the Diseases of Women and Children” which was opened on Union Quay on 4 September 1874. It moved to 46 Pope’s Quay on 31 October 1876 and to its present site on Infirmary Road on 16 September 1885. In 1901 its name was changed to “The Victoria Hospital for Women and Children”. Male patients were first admitted in 1914.

On 17 August 1914 the Hospital was registered under the Companies Acts, 1908 and 1913 under the name of “The Victoria Hospital, Cork (Incorporated)”. Reading the memorandum of association, the objects of the hospital were to provide a house or hospital for the reception, maintenance, medical and surgical treatment of Women and Children during sickness, and to furnish advice, and where possible medicine, to those who could not be admitted into Hospital. The Council or overseers of the Hospital comprised members of the Protestant faith. They could set apart rooms in the Hospital for the reception of private and semi-private patients, as well as wards for the reception of ordinary patients. They could make changes for the use and treatment as the Council wished and oversaw the payment in whole or in part from or on behalf of any patient.

Soon into the first couple of months of World War I, October 1914, ward spaces were assembled for the treatment of wounded soldiers. They were brought to Cork by the 562-bed hospital ship HMS Oxfordshire, which was overflowing with wounded by the heart of the war years. Recent work by UCD’s Centre for the History of Medicine in Ireland discovered that during World War I some 20,000 soldiers, principally from Ireland in the first place, were transported home and distributed between several military hospitals in Dublin, Cork and Belfast. They were housed also in wards in 40 civilian hospitals in Belfast, Cork and Dublin to provide accommodation and medical treatment for soldiers Patient beds were financed through a subvention from the War Office and, after the war and into the 1920s, the Ministry of Pensions.

The Victoria Hospital received fifty-five pounds from the War Department for treating the wounded soldiers. Compared to ordinary paying patients, this was not huge. The Council of the hospital gave an undertaking that they would at any time take in 30 soldiers and six officers. By 1916, the figure had risen to 130 cases.

Some 3,300 Irish doctors and medical students were involved in the war, of whom 243 died. The Victoria Hospital was deprived of the services of Dr C B Pearson and Dr R C Cummins, both of whom were serving in the Royal Army Medical Corps.

Lady Barrymore or Dorothy Elizabeth Bell of Fota House, funded the provision of a Rontgen Ray apparatus or an x-ray machine, which was greatly needed to assess bone damage. The year 1914 coincided with Polish born chemist Marie Curie developing radiological cars to support soldiers injured in World War I. The cars would allow for rapid X-ray imaging of wounded soldiers, so battlefield surgeons could quickly and more accurately operate.

At the annual general meeting for 1918, and as outlined in the Cork Examiner on 25 March 1918 the Honorary Secretary’s report stated that the wounded men were not being sent direct from France to Ireland. The secretary regretted that so little use has been made during 1917 of the military wards; “it was the keen desire of all connected with the hospital to do everything possible in caring for as great a number of these men as space would permit; but during the past year very few convoys have come to Cork, and there does not appear to be any probable increase as wounded men are no longer”. The soldiers’ ward, which was opened in October 1914, was closed in September of 1917.

In March 1918, the Cork Examiner outlined that the annual report stating that the hospital made a slight loss over the year. An increase over the year of £92 in the cost of provisions was not deemed what was described as a “very heavy item” but the cost of maintenance per patient had increased. In 1913 the maintenance cost was £78 per patient, rose in 1916 to £85, and in 1917 jumped up to the alarming figure of £106. The number of patients treated during the year was – 2,728 extern and 367 intern of whom 45 were soldiers and 76 free cases.

During the year the Victoria Hospital received notification of a generous legacy which had been left to the hospital by the late Mr Gumbleton, consisting of £1,000 in cash, and some valuable china, which had since been sold for between £300 and £400. Votes of thanks were passed to the committee of the Cork Hospital Saturday Society and Cork Hospital Aid Society for grants received, to the ladies and gentlemen who contributed to the hospital funds by personal subscription to all those who assisted in organising entertainments for the benefit of the hospital, and to Lady Carbery and the ladies of the Tabitha Guild, who devoted so much time to make clothing for the young patients.

Historical walking tour: Saturday, 24 March 2018, The Friar’s Walk, with Kieran; discover Red Abbey, Elizabeth Fort, Callanan’s Tower and Greenmount area; meet at Red Abbey tower, of Douglas Street, 12noon (free, duration: two hours) in association with Cork Lifelong Learning Festival 2018.

Captions:

938a. Victoria Hospital present day (picture: Kieran McCarthy)

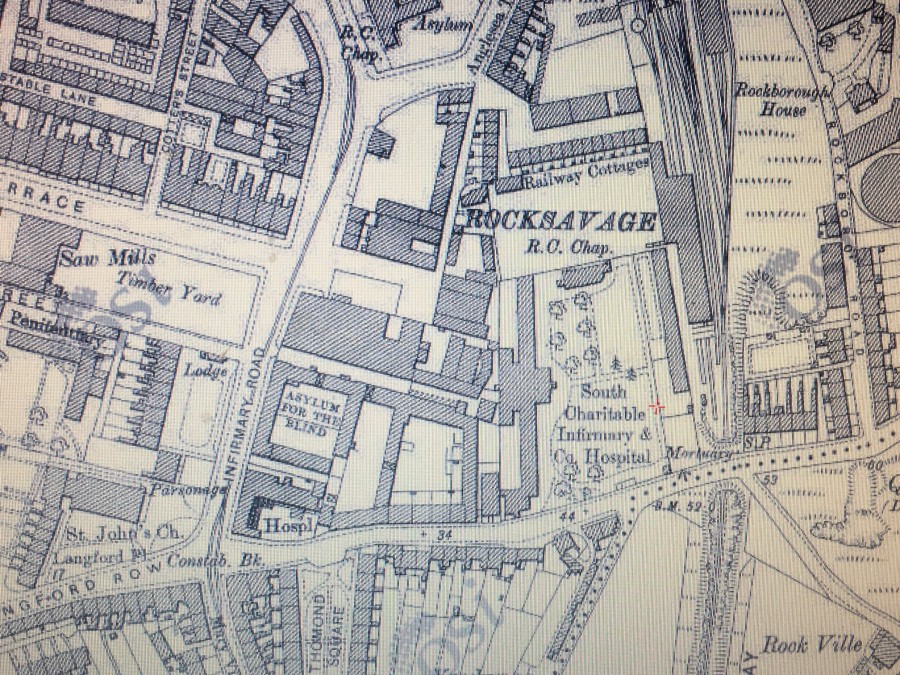

938b. Map of the grounds of the Victoria Hospital and South Infirmary, c.1910 (source: Cork City Library)

Kieran’s EU Local Event, Tuesday, 27 March 2018

Spring sunshine walk, 19 March 2018

Great afternoon for a bank holiday walk on Cork’s Marina and around the Atlantic Pond 🙂

Cork’s Marina, originally called the Navigation Wall, was completed in 1761. In 1820, Cork Harbour Commissioners formed and purchased a locally built dredger. The dredger deposited the silt from the river into wooden barges, which were then towed ashore. The silt was re-deposited behind the Navigation Wall. During the Great Famine, deepening of the river created jobs for 1,000 men who worked on creating the Navigation Wall’s road – The Marina. The environs is also home to three rowing clubs – the Lee Rowing Club founded in 1850, which is the second oldest club in the country; Shandon Boat Club, founded in 1875, and Cork Boat Club founded in 1899 by members of Dolphin Swimming Club – all of which ply the waters of the river regularly and who have annual regattas.

St Patrick’s Day Parade, Cork, 17 March 2018

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 15 March 2018

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 15 March 2018

Stories from 1918: Death of John Redmond

News of the death of Irish Nationalist leader John Redmond reached Cork on Wednesday 6 March 1918 with a heavy sense of shock. His last visit to Cork was towards the end of September 1917 when the Irish Convention sat for three days in Cork. The flags over Cork City Hall, the Harbour Board, and the several public buildings and clubs in the city, as well as some ships in the harbour.

John Redmond (1856-1918) was born in Wexford into a Catholic gentry family, he was educated at Clongowes Wood College, Clane Co. Kildare and at Trinity College, Dublin. After graduating he became a clerk in the House of Commons and devoted his life to politics. Young John Redmond was returned unopposed for New Ross, early in 1881. Very soon Charles Stewart Parnell appointed him as party whip, with the special duty of organising the Irish vote in the industrial cities of Britain. The Irish voters became a decisive factor in many such places. In the following years Redmond’s command of the Irish vote in Britain, reinforced by his own persistent and convincing narrative for Home Rule, counted enormously.

John Redmond continued as leader of the Parnellites until the re-union of the Nationalist Party in 1900. He lost his former seat in County Wexford, but he soon won Waterford City as a Parnellite. He continued to represent Waterford until his death in 1918.

As the young leader of the Parnellites, John Redmond also began to show remarkable abilities as a debater and as a parliamentary tactician. For five years, between 1909 and 1914, John Redmond attained a position of almost unchallenged authority as leader of the Irish nationalist forces both at home and overseas. It was a position that even Daniel O’Connell and Parnell had never occupied. He counted on the support of highly organised Irish associations all over Britain and the USA, and in Australia and other countries.

By the summer of 1914 John Redmond had reached a point at which self-government for Ireland, without Partition and with full scope for future enlargement of its powers, was accepted as inevitable within a matter of months. However, the outbreak of World War I scuppered these plans.

June 1917 coincided with the ground being laid for further national discourse on the future government of Ireland in the form of the Irish Convention. In a letter dated 16 May 1917 and addressed to Mr John Redmond, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, the Prime Minister Lloyd George expressed his hope that “Irishmen of all creeds and parties might meet together in a Convention for the purpose of drafting a constitution for their country which should secure a just balance of all the opposing interests”. Invitations were extended to the Chairmen of the thirty-three County Councils, the Lord Mayors or Mayors of the six County Boroughs. The Chairmen of the Urban Councils throughout Ireland were requested to appoint eight representatives, two from each province. The Irish Parliamentary Party, the Ulster Parliamentary Party and the Irish Unionist Alliance were each invited to nominate five representatives. The report of the outcomes of the Convention were compiled and published by Horace Plunkett in 1918 but came too late as the conscription crisis overshadowed its release and Sinn Féin continued their re-organisation.

On Saturday 16 March 1918 the remains of John Redmond were laid to rest in the family vault in his native Wexford. On Friday his exiled compatriots in London, and representatives of the British, French, Belgian, Italian and American nations, joined together in praying for the soul of Ireland’s dead Leader. It was not until the remains of Ireland’s great political Leader had been borne across the Irish Sea and had touched Irish sort that the full fervour of his countrymen’s respect were made manifest. People gathered from all parts of Ireland to mark their appreciation of his life work. Beside his grave, Mr John Dillon, his successor, gave the oration. Mr Dillon came of a patriotic stock, and his father, John Blake Dillon, was a follower of Daniel O’Connell, and subsequently of Smith O’Brien, and later became one, of the founders and proprietors of The Nation newspaper. He was also MP for Tipperary for a time. Mr Dillon represented East Mayo in the British Parliament since 1885 – a record of continuous service. He was also a leading land reform agitator as member of the original committee of the Irish National Land League spearheading the policy of “boycotting” advocated by Michael Davitt with whom he was allied in close friendship.

John Redmond was honoured in name in a prominent Cork street and a sporting Club. In 1902, to mark John Redmond’s achievements, Mulgrave Road in Shandon was renamed Redmond Street. In the late 1830s, Mulgrave Street was developed to provide more direct access between the Butter Exchange and the docks on the east side of St Patrick’s Bridge. The project was financed by Cork butter merchants and named after the Earl of Mulgrave, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. Redmonds GAA club was founded in 1892. In the early years of the GAA, clubs represented their county in the All-Ireland championships. Redmonds were involved in the Senior Hurling Championship finals ten times from 1892 to their last finals appearance was in 1927.

Captions:

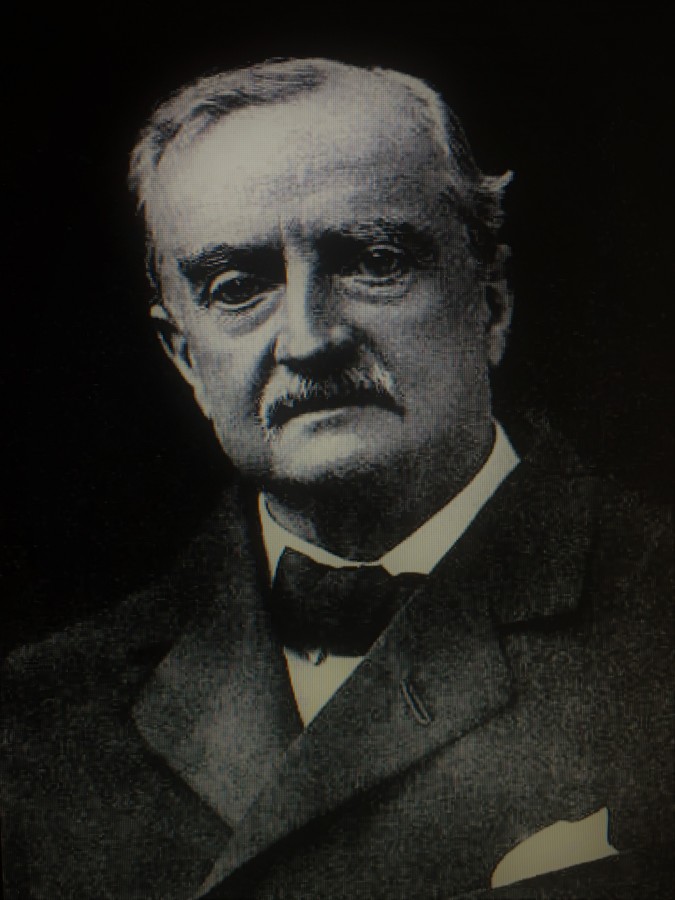

937a. John Redmond, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party (source: Cork City Library).

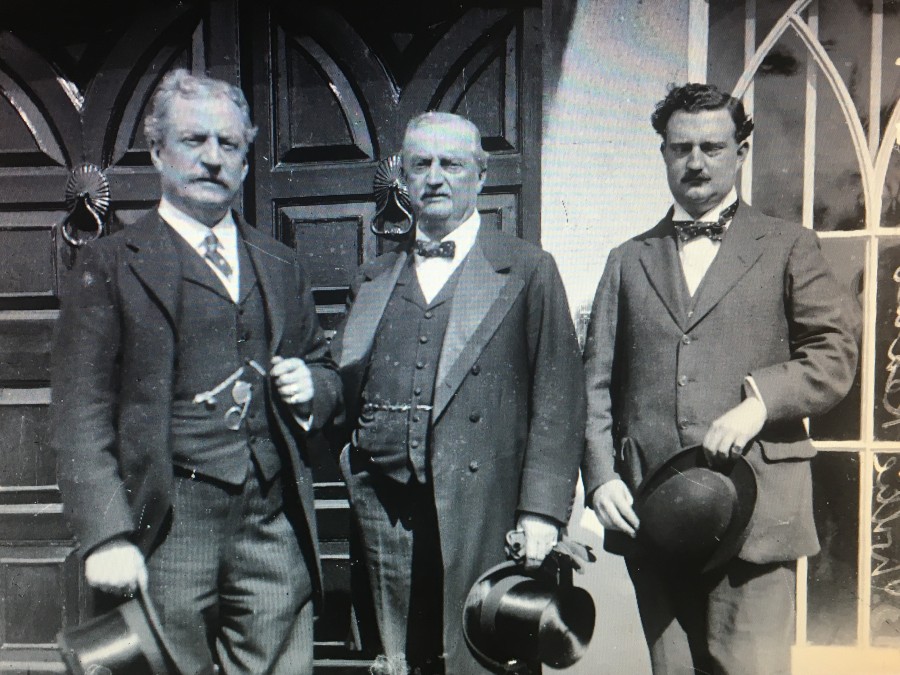

937b. John Redmond (centre) in 1912, with his brother Willie (left) and son, Capt. W.A. Redmond (right) (source: National Library of Ireland).

Kieran’s Question to CE, Cork City Council Meeting, 12 March 2018

Cork Lifelong Learning Festival 2018

The eagerly awaited 15th Cork Lifelong Learning Festival will take place from Monday 19 – Sunday 25 of March 2018. The annual festival has grown year on year since 2004 and lives by its motto of ‘Investigate, Participate, Celebrate’, with the public encouraged to do just that by trying out new experiences, participating in events and enjoying demonstrations of skills both new and old.

A week of hundreds of free events are aimed at all ages, from the very young to the young at heart, and all Lifelong Learning Festival events are open to all. The exciting programme includes performances, poetry, workshops, walks, displays and demonstrations, and really does have something for everyone. The only limit is your appetite to try something new. Some events can be in high demand so check the programme to see if you need to book.

Events, which aim to be accessible to all, take place right across Cork city, and into the county, in a variety of venues indoors and out, including shopping centres, libraries, museums, community and resource centres, parks, colleges, private businesses and on the streets.

Newly appointed Festival Organiser Siubhán Mc Carthy says: “Cork loves learning and to prove it we have a packed programme of free, accessible events open to all, regardless of your learning abilities or ambitions; I guarantee you’ll find something during festival week that you want to know more about. Learning is not just about gaining qualifications, it’s also about making life more fulfilling and enjoyable and I passionately believe in the power of knowledge to change lives for the better”.

This year’s festival includes four free seminars covering subjects as diverse as social inclusion to entrepreneurship and six ‘Learning Factory’ events across the week, in conjunction with CIT, which give an insider’s look at some of Cork’s most innovative businesses – including a guided tour of Inniscarra Dam. All events are hosted by volunteers be they individuals, community organisations, private businesses, schools or colleges.

The festival is a key part of the City’s strategy of making Cork a Learning City. Its success was recognised by UNESCO when Cork was one of the first 12 cities in the world to receive a Learning City Award in 2015 and Cork recently hosted UNESCO’s 3rd International Conference of Learning Cities in September 2017.

The free printed festival programme is out now and available in libraries, City Hall, the Tourist Office on Grand Parade, or from host venues

See the programme online at www.corklearningcity/lifelonglearningfestival

Kieran McCarthy, Historical Walking Tour, 24 March 2018

Saturday, 24 March 2018, The Friar’s Walk, with Cllr Kieran McCarthy; discover Red Abbey, Elizabeth Fort, Callanan’s Tower and Greenmount area; meet at Red Abbey tower, of Douglas Street, 12noon (free, duration: two hours) in association with Cork Lifelong Learning Festival 2018.

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 8 March 2018

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 8 March 2018

Stories from 1918: The Sinking of the SS Kenmare

The SS Kenmare, one of the fleet of the Cork Steam Packet Company, was torpedoed in the in the Irish Channel on Saturday, 2 March 1918, between Holyhead and Rockabill Light, on a voyage to Cork, under the command of Captain Peter Blacklock. Of the crew of 35 there were only six survivors. Amongst the 29 lives lost was Captain Blacklock, a native of Liverpool but who has resided for some years in Cork.

The Dublin correspondent of the Central News, in a graphic account of the sinking of the Kenmare, noted that the sinking occurred at seven o’clock on Saturday evening, and was without warning. Many of the men were in their bunks at the time, and were awakened by a loud explosion, which almost shattered the vessel. Rushing quickly on deck, they found the vessel awash. Only one small lifeboat, which was not lashed got clear. Its three occupants succeeded in rescuing some men from the water. Owing to the wreckage, they were unable to get to everyone, who were shouting for help. After ten minutes the distressing cries died away, and the survivors in the small boat drifted for twelve hours before being picked up. They were scantily clad and suffered terribly from the cold. Though all the survivors believed the sinking was caused by a submarine, none of them saw an enemy craft or the wake of a torpedo. The vessel appeared to have been struck amidships and sank in about a minute after the explosion.

In a media interview, crewman Tim O’Brien, of Cork, believed the ship was torpedoed. He was in his bunk at the time, in the steerage over the propeller, and was thrown by the force of the explosion some yards. The lights went out immediately. Four other firemen were sleeping in the room. There was some confusion in the darkness but he succeeded in a getting a flash lamp and his lifebelt and made for the deck followed by James Barry. When Tim got on the deck the ship was sinking fast. As with Mr Evans he got into one of the lifeboats and floated off the ship. As they were leaving the ship they grabbed another crewman and pulled him into the boat. At this time the captain was on the deck shouting instructions as to the lowering of the boats. After leaving the sinking ship they rescued the carpenter and a gunner from the water.

Meanwhile 25 of the crew had put off in a boat, which became upturned and from which only one man, James Wright was rescued. He was found with his head through the bottom of the boat, and rescued him with great difficulty, he being powerless to assist, as one of his arms was broken. They remained in the vicinity for a quarter of an hour in the hope of picking up other men. At about seven o’clock in the morning the survivors were picked up by a small coaster. They were then nearly dead with the cold, the majority being only half-clad. Tim O’Brien was in his shirt and trousers. The night was very cold, and a heavy sea was running.

James Wright, Chief Steward, who had sustained a fractured arm and was badly bruised about the left eye, told how he was talking to Captain Blackpool in the latter’s cabin just before the vessel was struck. It was just twilight, and nobody saw the submarine. A terrific explosion was the first he knew of anything happening. The SS Kenmare immediately took a big list and commenced to go down by the stern. In a minute and a half or two minutes at the most the ship had disappeared, and he was struggling in the water. When he and the captain realised what had happened they both rushed out on this deck and lowered one of the boats. This was upturned by the suction of the sinking vessel, and they were all thrown into the sea.

Heart-rending scenes were witnessed at the offices of the Steampacket Company on Penrose Quay, when relatives of members of the crew formed a constant stream of callers to ascertain if any news was to hand. Among the earlier visitors was the daughter of Captain Blacklock who was not among the survivors.

Relatives of nearly all the members of the crew visited the offices, and when it was revealed that only six out of thirty-five were saved there was much shock and devastation. Amongst those saved was Mr Barry – the oldest person aboard, and possibly the oldest man sailing in the company’s service. Amongst those missing was the Chief Engineer, Mr Thomas Murphy, the son of Mr Murphy, Woodland View. Strangely enough when in a different service Thomas’s ship was torpedoed, and though that vessel carried a very large crew they were nearly all saved. He had been sailing in the SS Kenmare for some little time back relieving a Mr O’Sullivan, Knockrea Terrace Blackrock Road. The Quartermaster, Geoffrey Grant who resided at Hibernian Buildings, who with his nephew, Mr Moore were also amongst the missing. Mr Grant was the father of five children, and four years earlier he had buried his wife.