Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 26 February 2015

Cork Harbour Memories (Part 12)

– Medieval Pomp: Bread Checks and Dart Throwing

The charters granted to Cork in the Middle Ages created many of the traditions this city still participates in today. Following on from last week, in constructing an identity for the walled town of Cork, Edward II’s charter dated 20 July, 1318 confirmed previous charters and encouraged pomp and ceremony for the election of a mayor. The charter noted that the elected mayor could be sworn before his predecessor in Cork, instead of going to Dublin for the purpose of taking an oath before the Barons of the Exchequer.

Edward II’s large debts (many inherited) and the Scots’ victory at Bannockburn by Robert the Bruce in 1314 made Edward unpopular. Edward’s victory in a civil war (1321-2) and such methods as the 1326 ordinance (a protectionist measure which set up compulsory markets or staples in 14 English, Welsh and Irish towns for the wool trade) did not lead to any compromise between the King and the nobles. His new regulatory frameworks perhaps also aimed to empower townspeople and those he governed. Such protectionist measures he rolled out in Cork some years previously in the 1318 charter to Cork. It granted to the mayor and bailiffs the assize of bread, which regulated the price, weight and quality of bread, and certain other unrecorded privileges usual in charters of that period. It is the first mention of the regulation of the production of food in the historic records.

The charters of 1330, 1331 and 1381 reconfirmed previous ones. Fast forward to the next one granted by Edward IV dated 1 December, 1462 and it states that the Mayor and Commonalty took taxation from eleven parish churches in the city and in the wider suburbs. The churches paid a rent of 80 marks annually to the Crown, so long as the suburbs remained undestroyed. A comment was made that in the 1410s, the suburbs had been attacked by what is described as “Irish enemies and English rebels”. The churches were unable to pay their rent and the town paid the taxation to the crown for them. The churches were to pay back their arrears, and were responsible for part payment for maintaining the walls until peace was restored to a one mile circumference of the walled town.

The hills and valleys of County Cork were not Edward IV’s only worry. In the wider context two years earlier to the Cork charter in 1460 on the death of his father and brother, in contest for the throne, at Sandal Castle, Wakefield, Edward inherited from his father the Yorkist claim to England’s throne. Edward proved to be an able general, defeating the Lancastrians in February 1461 after which he was proclaimed king in London. He achieved a further decisive victory over the Lancastrians in Yorkshire, on 29 March, Palm Sunday. Fought in a snowstorm, it was to be the bloodiest battle of the Wars of the Roses, with casualties reported to be in the region of 28,000. The victorious Edward, then aged nineteen years of age made a state entry into London in June and was crowned King of England at Westminster.

Fast forward again and the interest in securing the wider Cork region by the English monarchy especially Cork Harbour was revealed in Henry VII’s charter, dated 1 August 1500. Henry VII ended the dynastic wars known as the Wars of the Roses, founded the Tudor dynasty and modernised England’s government and legal system.The waters of a harbour like Cork was an English highway to move goods, people and ideas around. For Cork Henry confirmed all former charters, and further granted that the Mayor and citizens, and their successors, could enjoy their franchises within the city, the suburbs, and every part of the harbour. The charter reveals the extent of land to be the metropolitan area in a sense in Cork Harbour; “As far as the shore, point, or strand called Rewrawne, on the western part of the said port, and as far as to the shore point or strand of the sea, called Benowdran, on the eastern part of the same port, and as far as the castle of Carrigrohan, on the western side of the said City and in all towns, pills, creeks, burgs, and strands in and to which the sea ebbs and flows in length and breadth within the aforesaid two points, called Rewrawne and Benowdran” (better known by their modern names of Cork Head and Poer Head).

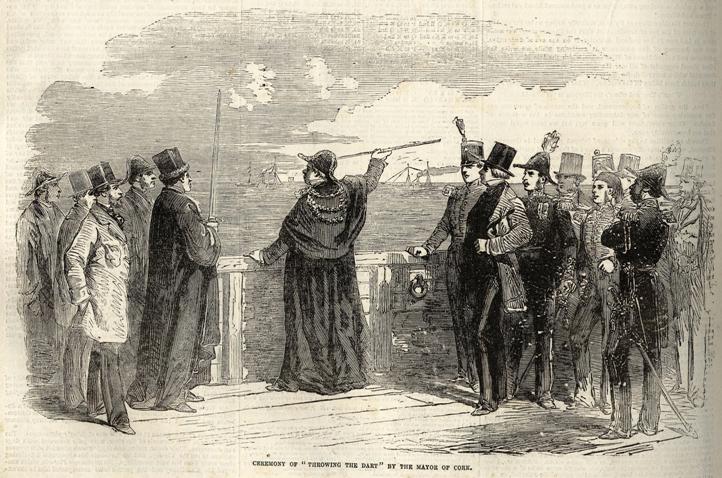

In time and arising out of the Mayor having jurisdiction over the harbour the ancient ceremony of Throwing the Dart emerged. It is unknown when the ceremony began – maybe circa 1610 – a similar ceremony began in Limerick 1609 and Waterford in 1626. The earliest written record of the custom of claiming the waters in Cork is to be found amongst the archives of the Corporation and transcribed in a very insightful book by Richard Caulfield, entitled the Council Book of the Corporation of Cork published in 1876. Under the date of 30 May 1759, the mayor sought the arrangement of entertainment at Blackrock Castle and he, his officers and Corporation were to go to the mouth of Cork Harbour for the dart ceremony.

To be continued…

Kieran’s new book, Cork Harbour Through Time (with Dan Breen) is now available in Cork bookshops.

Caption:

781a. Throwing the Dart ceremony with Mayor and officials, mouth of Cork Harbour, 1855 (source: Illustrated London News, Vol. 26, 1855, p.531, 2 June 1855)