Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 31 October 2024

Making an Irish Free State City – Sunbeam & the Future of Fashion

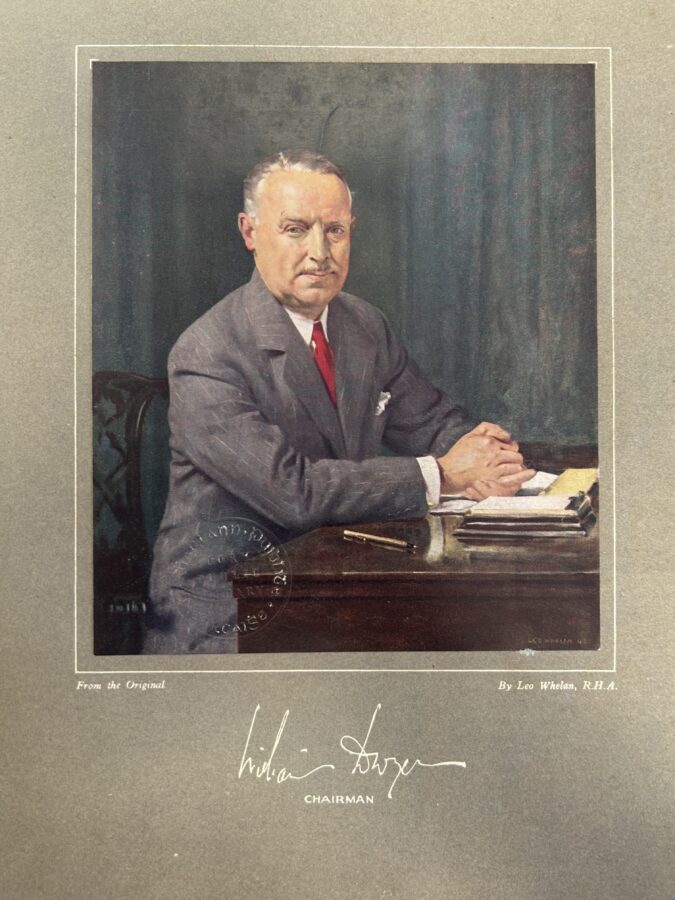

In the days surrounding the formal opening of Sunbeam Knitwear Company in Blackpool on 5 March 1933, there was much press coverage. William Dwyer had launched an important scheme to produce silk and artificial silk hosiery, most of which up to that point was imported from abroad.

To be successful William Dwyer deployed all highly strategic elements including future thinking investment, being proactive and responding to the changing fashion styles especially in female underwear in the early 1930s, harnessing the use of more modern machinery and manufacturing, making sure his staff were well-trained on the factory floor and undertook the head hunting of a strong sub management team. In particular William hired designers who watched and responded to the fashion changes in Paris and London, the rapid emerging cultural trends in elaborate stocking design and seeing what shapes and designs suited Irish figures and Irish complexions. All the above elements together made for a company well poised to react to economic, social and cultural trends of their time and almost challenging indirectly the culture of conservative Ireland.

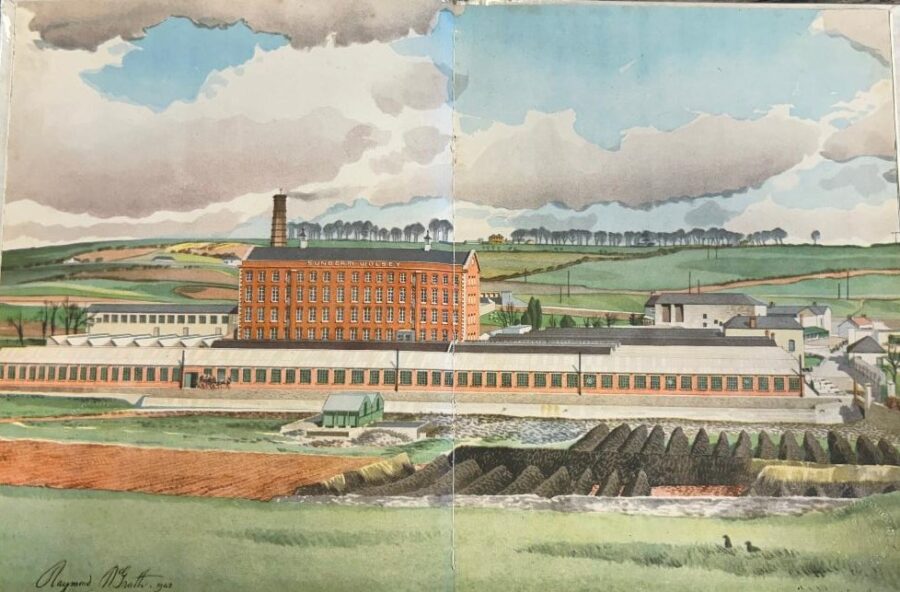

The Cork Examiner on 3 March 1933 carried a paid and well-designed and impressive “catch the eye” advertisement stating “ A New Home for a Mighty Irish Industry”. Adjacent was a page and half story on the story todate of Sunbeam and William Dwyer’s journey, with clear input by the Company itself. The newspaper opened its story by describingthe new Company premises standing on the Blackpool side of the city, closely adjoining the main Cork-Dublin railway line. The premises comprised some eight acres of factory space, together with one of the finest chimney shafts and boiler house equipment in the Irish Free State. The article describes a fine industrial building; “The building is particularly well constructed; it was designed to withstand the rigours imposed by the flax industry and is admirably suited for hosiery production. It is suitable, too, for the ambitious programme of expansion and development of new industries planned by William Dwyer when he undertook his project at Blackpool”.

The Cork Examiner article continued to explore the geography or layout of the factory. At the top of the factory was a “battery of nearly fifty machines” engaged on the manufacture of seamless silk stockings. These machines turned out the cheaper grades of artificial silk hose in an infinite variety of shades and colours, “designed by one of the most expert dyeing departments in the hosiery trade”.

In another part the making of fully-fashioned silk hose was concentrated. This was an article that according to William Dwyer, although limited in production because of its price, demanded much more attention in manufacture. There was one giant machine, nearly forty feet in length, which automatically turned out 36 stocking feet at once. The newspaper described its mechanism; “The mechanism of this machine is marvellous. It was designed and produced in Germany. Similar machines are utilised by the most famous fully fashioned hose makers in Great Britain and the Continent”.

Lying beside the giant machine was a machine where the rest of the stocking was made. The Cork Examiner notes of the complicities of the machine: “ It looked, if anything, even more complicated, and as it silently revolves and its cases turn over and over it is easily realised what genius is in its design, and what intense experience and knowledge are required to maintain and to operate such an ingenious unit of production”.

At another part of the factory the Cork Examiner article related that there was a plant of machines for making ladies’ silk hosiery, which were to be sold at a lower price. These were America-made machines. They were the very latest type of machine on the market and were the “very finest gauge made”. They were 300-needle machines. These machines produced semi-fashioned silk hosiery at popular prices and were the only type of machines manufactured, which produced an elastic re-enforced welt. They also made a gusset toe, which added enormously to the comfort of the stocking. The variety of stockings that can be made on these machines is practically limitless, from ladies’ art silk stockings to the finest fishnet and clock stockings.

The Cork Examiner continued that then came the bulk production of socks and stockings; “Hose and half hose as the trade knew them – coming into existence from mighty machines in millions, packed into neat bundles with intriguing little trademarks, waiting their time for despatch to every corner of the country”.

The Cork Examiner remarked of the use of reinforced welts on stockings; “there were flat look machines for attaching the ribs; a welt which makes perfectly flat seams without any welt whatever. There are also machines, which sew on buttons at the rate of six dozen a minute”.

Through the main factory there were banks of machines turning out woollen underwear that were deemed “essential to health and wellbeing”. In addition to woollen goods here was made underwear or a new kind of artificial silk.

Another part of the factory devoted itself to as the Cork Examiner described “curiously-patterned golf stockings, another to daintily-coloured kiddies’ stockings – lines that until a few short months previously were never made in the Irish Free State”. Even green stockings were made by Sunbeam—made for the Rugby and football teams.

A department specialised in the making of outer wear, which included fashion garments, costumes, all and every kind of jumpers, pullovers, scarves, etc. In anotherspecialised department, Sunbeam golf pullovers were made. The Cork Examiner wrote about their speciality; “No ordinary pullovers were these – for as the foreman shows them he proudly tells of their special waterproof quality, cups a portion of the garment into his hand and fills it with water just to prove that rain cannot get through”.

Down in the basement of the factory was the dye-house, where steam rose from the ground and coloured liquid flows along channels. The Cork Examiner noted: “Here the science of art and of chemistry ensures success to the rest of the manufacturing processes. Everything in a hosiery business depends on the quality of a dye – the vastly different shades, and how consistently and regularly those shades come out in the garments that are made”.

To be continued…

Caption:

1277a. Sunbeam Knitwear Ltd, Cork, Cork, Ireland, 1933; Oblique aerial photograph taken facing south (source: Britain From Above, Reference number: XPW042276 Ireland)