Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 17 October 2024

Making an Irish Free State City – Arise the Sunbeam Knitwear Company

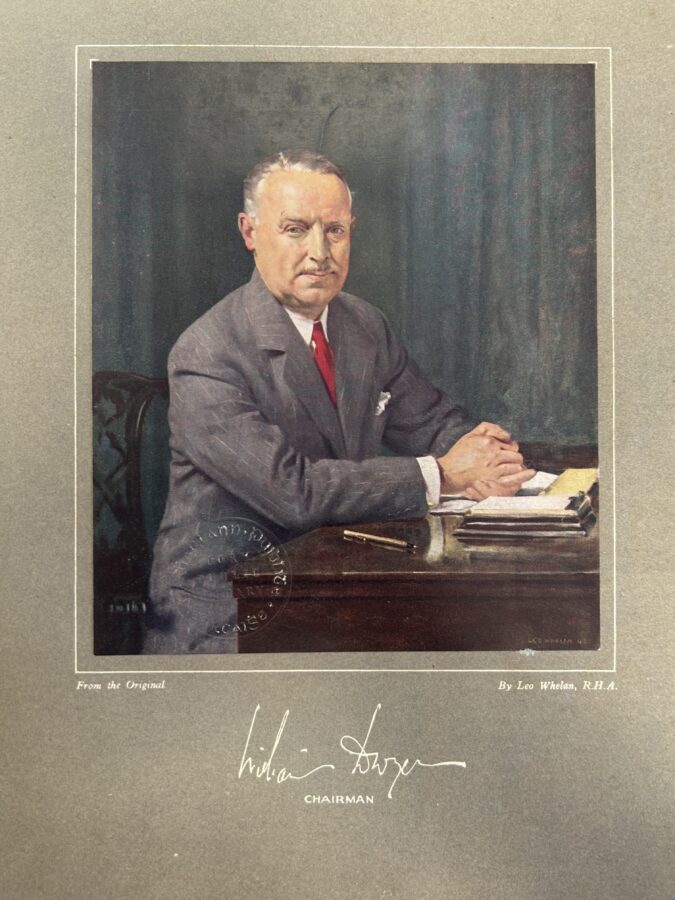

The opening of the Sunbeam Knitwear Company at the historic Butter Exchange Building in 1928 by William Dwyer (1887-1951) was the start of his enormous journey of industrial development in Cork. It also provided much needed employment opportunities for Cork in the fledging Irish Free State. William became one of the country’s foremost industrial figures.

On finishing at Presentation College, Cork and in Downside School in Somerset, William initially worked for Dwyer & Company on Cork’s Great George’s Street and gained a great grounding in business acumen. It was established by his grandfather and specialised in the manufacture of clothing for men and boys.

In 1928, William went out on his own and took out a lease of the historic Butter Exchange building and established Sunbeam Knitwear Company. It manufactured knitted underwear. Four of the core machines had been rescued or purchased by William from the ruins of Bandon Hosiery, which had been burned out by British Forces, some years previously in 1920.

In late February 1929, the new Sunbeam Knitwear Company took part in the two week Cork Examiner Ideal Homes Exhibition, which covered a wide variety of modernity trends for the home including furniture and furnishings and also clothing styles.

A week later on 9 March 1929, a Cork Examiner journalist followed up with the Company on how they got on at the Exhibition. It was part of a reflection by the newspaper on the importance of the exhibition. The newspaper highlighted that a stall was taken by the Sunbeam Knitwear Company with “no very great expectations”. Owing to the stall’s limits only a small range of products could be shown, namely ladies’ fashioned outerwear. However, successful results of the display were immediate. The journalist related that although the factory plant output had been very much increased just before the Exhibition, the exhibition display resulted in a steadier flow of orders.

In a general way commenting on the first year of operation of the Sunbeam Knitwear Company, the Cork Examiner journalist commented that the “results quickly began to exceed all expectations”. The newspaper highlighted that the fledging company found itself working at full pressure to cope with the demands for its products. They considered that they were underselling the English market while maintaining a very high standard of quality in their manufacture. Referring to the modern plant, such as what William Dwyer had installed, the journalist detailed that “one girl can supervise the work of six machines, each of which has a capacity of 36 to 40 dozen pairs per week”.

The Cork Examiner further related that the bulk of the yarn was bought in white wool. It was first of all dyed to the desired colour. In the case of garments the wool was knitted on circular machines, which could be set to do all kinds of fancy work at an rapid rate and with the pattern absolutely automatically following cut. There were five such machines and each one was capable of dealing with 100 lbs. weight of fabric per day. The article denotes; “This was made up into all sorts of men’s, women’s and children’s outer wear, including sports’ apparel, the wide range extending to 100 different garments and at prices ranging from for retail purchase, from about 4s 11d to 30s per garment”.

Hose and half-hose were manufactured in large quantities, from the heavy sort, for country requirements, to the very finest, in a variety of fancy patterns. In the sports outfitting department, the Company had created a big demand. Cork alone supplied orders for over 200 dozens of football jerseys in the previous season. Such products had been selling in all parts of the Irish Free State. Trade queries had also come from outside the Free State and the Company was hoping to soon create an export trade in several directions.

The Cork Examiner pointed out that the Sunbeam Knitwear Company prided itself on the fine quality of and on the extent of designs of finished garments. Such garments catered for all tastes. In the sphere of really high-class knitwear, the journalist argued that “it would be difficult to excel the splendidly finished manufactures, such as ladies’ fashioned three-piece suits and fashioned pullovers and cardigans”.

The Cork Examiner article ends with positivity of hope for such industries as Sunbeam Knitwear Company; “Thus from a modest beginning has grown an industry which Cork people, most of all, should support in its present flourishing state so that its future may be as bright and prosperous as has been the short period of its establishment. When people beyond Cork can see the benefit to themselves of buying the products of such a factory surely those at home ought to reap the double benefit, which a prospering concern of this kind confers on them and on their city”.

An interview recorded by the Northside Folklore Project in 2002 highlights the story of one of the workers, Nancy Byrne, in the Shandon premises. Nancy recalled a staff of about fifty in one large room with an open basement and recalls the dyeing process and machine work; “An Englishman, Mr Howarth was the dyer. The raw wool that was brought coloured and dirty cream, how lovely it came out of the dye house in the various colours. On the main floor were many of the different machines, stocking for making wool sacks, flat for wool jumpers which would be put together by overlock workers or sewing machinists. Here also tables were provided for hand-finishers or menders. It was usual to find a small hole here and there in a garment due to the knot in the thread or breaking”.

Nancy also remembered her role as a machinist; “Here I sat in front of a long bench at an electric sewing machine with around three other girls. On the opposite were the overlockers and they worked machines also, finishing off the inside of woollen garments. My task being to stitch up the side of children’s tops. [Sic]. They were a fawn satin without sleeves and later we would attach them to the skirts. We worked from eight to six; the office workers’ hours were nine to six”.

In Guy’s Almanac and Directory of Cork for 1930, three directors are listed for the Sunbeam Knitwear Company – William Dwyer, David Arlson Smythe of Malone Park, Belfast and John O’Donovan, Grenville Place, Cork.

Fast forward to 14 March 1932 and the historic Butter Exchange building was damaged by fire. The Cork Examiner recalls that the Cork Fire Brigade received a call at 8.35am to Church Street. There was a furnace inside the factory with an iron flue running through a wooden and rubberoid roof, which became overheated and it set fire to the latter. A line of hose was laid and after about an hour the fire was got under control. A considerable portion of the roof was destroyed, but any damage done to the interior of the factory premises was recorded as being slight.

The event though sped up William Dwyer’s expansion plans as several weeks later, he revealed his larger plans to take over the late nineteenth century buildings of Cork Flax Spinning and Weaving Company in Millfield, Blackpool and to create a larger premises for the Sunbeam Knitwear Company.

To be continued…

Caption:

1275a. Portrait of William Dwyer, circa 1943 (source: Cork City Library).