Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 9 December 2021

Journeys to a Truce: A Provisional Treaty is Signed

The first memo to the public was a short one on the outcome of the talks of the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921. It was hurriedly penned by Arthur Griffith, and issued to the world press directly after signing the Treaty on 6 December. It reads: “I have signed a Treaty of peace between Ireland and Great Britain. I believe that treaty will lay foundations of peace and friendship between the two Nations. What I have signed I shall stand by in the belief that the end of the conflict of centuries is at hand”.

It was a long and highly pressurised journey to an agreement for both sides. The threat of renewed violence hung over the signatories. The Treaty negotiations began in London on 11 October 1921. The British team was led by seasoned politicians Lloyd George and included Austen Chamberlain and Winston Churchill.

The Irish team was chaired by Minister for Foreign Affairs Arthur Griffith, after de Valera decided to stay in Ireland for strategic reasons. Arthur had established Sinn Féin in 1905 and nationally brought the party to the pinnacle of success in elections in 1920. Arthur was substitute president of Dáil Éireann for most of the War of Independence while de Valera was in America. With Arthur in London were Minister for Economic Affairs, Robert Barton and Minister for Finance Michael Collins. The other two Irish negotiators were solicitor Éamonn Duggan TD and Charles Gavan Duffy TD, a barrister and Dáil Éireann’s representative in Rome. The Dáil and de Valera described these representatives as ‘plenipotentiaries’, from the Latin for someone invested with full authority.

Over the seven weeks of negotiations, regional newspapers across the country reported on the tense negotiations and what was at stake between the two sides. The challenge of North Ireland and its historic loyalist base echoed throughout the myriad of news stories.

The discussions concluded in the early morning of 6 December 1921 with the signatures, by British and Irish negotiators, of ‘Articles of Agreement’ – better known as the Anglo-Irish Treaty (or the Treaty). The deal, as signed, was provisional, on consent in London’s Westminster and in Dublin’s Dáil Éireann.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty is a short document. It commences by declaring that the Irish Free State shall have the same constitutional status as the dominions of Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the Union of South Africa. This was a higher status than the previously sought ‘Home Rule’ for Ireland, and an achievement that was unimaginable when Sinn Féin was founded sixteen years earlier. The representative of the king in Ireland would be appointed in the same way as the governor-general of Canada.

Under the Treaty, Ireland also remained in the British Empire. For the first time in an official UK document the term ‘Commonwealth’ was used as an alternative to ‘Empire’. The final agreement did not require Dáil deputies to swear an ‘oath of allegiance’ to the king. The oath of allegiance was to the Constitution of the Irish Free State, with an oath of faithfulness to the monarch. Nevertheless, any oath to the king in any shape or form offended many Dáil deputies in their initial thoughts to the press.

The Treaty also gave the new state financial freedom, although the Irish agreed to pay a fair share of existing UK public debt.

Until the Irish Free State could undertake its own coastal defence, article six ensured that British forces were responsible for the defence by sea of Britain and Ireland. The Free State was also to let Britain use certain named harbours and other facilities. Initial thoughts by some Dáil deputies resented that Britain would retain ‘the Treaty ports’ of Cobh (then ‘Queenstown’), Berehaven and Lough Swilly. The issue of the Treaty ports was important because it made Irish neutrality quite impractical if not impossible in the event of war.

The Irish Free State agreed to pay fair compensation to public servants who were discharged or who retired because the change of government was not to their liking. This ‘article’ did not apply to the Auxiliaries and Black and Tans.

The Treaty gave Northern Ireland the right to opt out of the new Irish state; if it did so, however, a boundary commission was to be set up to “determine in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants […] the boundaries between Northern Ireland and the rest of Ireland”. Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins believed that this would transfer counties Tyrone and Fermanagh to the Free State. But the procedure was a major sticking point for many Dáil deputies in their initial thoughts to the press. Even after 1922, however, the Boundary Commission never worked as they had hoped, and the border remained unchanged.

Overall, though in the days that followed the signing on 6 December, the Irish negotiators though not happy with the terms, were told by Lloyd George that non-acceptance would lead to a resumption of the war, which, at the point the Truce was called, was being lost by the IRA. The delegation recommended the Treaty to Dáil Éireann.

In those early days post the signing, a minority of Dáil deputies, including its president, Éamon de Valera, maintained that the Treaty did not go far enough and that the new state must be a republic outside the Empire (although perhaps associated with the Commonwealth externally). Some thought that fighting should resume, in an effort to force Northern Ireland into an all-island state. For others, an Irish Republic already existed and acceptance of the Treaty would substitute this with something less and accepting the Treaty meant voluntarily going ‘into the Empire’ for the first time.

The majority of deputies argued that the Treaty was a stepping-stone to greater independence. Between the signing of the agreement in December 1921 and its ratification in early January 1922 a series of progressively bitter debates occurred in Dáil Éireann.

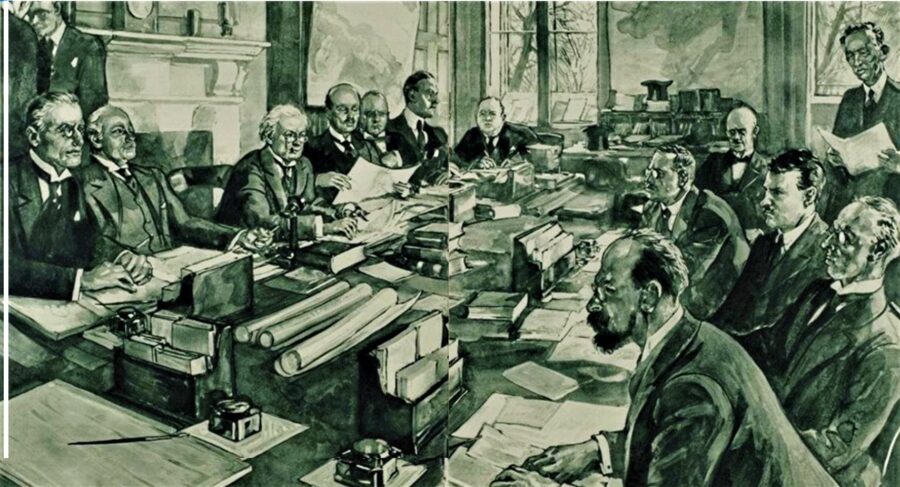

Caption:

1129a. An artist at the Illustrated London News captured the British and Irish Treaty negotiation teams at work (source: Illustrated London News, December 1921).