Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 11 February 2021

Journeys to a Truce: The Compensation Claims Begin

This month, one hundred years ago, the Recorder or Chief Magistrate for Cork City, Matthew Bourke, began the municipal hearings for the compensation claims arising out of the Burning of Cork in December 1920. A total of 682 claims were before him and they were to occupy the court for several weeks. A handful were written up in the Cork Examiner and reveal the depth of the damage done but also the early steps being taken to rehabilitate livelihoods and building stock in the city centre.

On 17 February 1921, the first case taken was that of the proprietors of the Munster Arcade – Messrs Robertson, Ledlie, Ferguson and Company, who claimed losses of £405,000. On top of this there was a claim by the landlord of the premises Charles Harvey. The two sets of solicitors present J J Horgan and Messrs Staunton and Sons put forward their respective cases. Mr Horgan described uniformed crown forces, converging on the Munster Arcade in the middle of St Patrick’s Street on 11 December 1920 after setting Grants and Cashes on fire. He continued to detail the blowing in the front windows and the throwing in of explosives. With the front on fire, the five or six employees in the building made their way to the door leading to Elbow Lane.

The employees were met by several uniformed men and held up. Some of the men entered the premises taking with them explosives and tins of petrol and a bag containing some heavy substance. They went upstairs and set fire to the other parts of the premises. Meanwhile, the employees were let go at the door but were met by another party of uniformed men who told them to go back and shots were fired at them. They finally managed to escape into Cook Street and took refuge in a house there.

The Munster Arcade also had premises in Oliver Plunkett Street, where a furniture business was mainly carried on, and these were destroyed completely. With regards to damages, it was estimated that it would cost at least £93,450 5s 1d to rebuild this latter building. They had a cabinet factory at the other side of George’s Street, which would cost £7,774 5s 9d to rebuild. Then there was a laundry and shirt factory held under a yearly tenancy in Robert Street, the contents of which were valued at £583 9s 2d. They were not making a claim for the reconstruction of these premises as they were only yearly tenants, but he understood that a claim had been lodged by the owner.

Then there were the interior fittings and equipment on the St Patrick’s Street site. With regard to the stocks, every single item was destroyed, but fortunately the books were kept in a fireproof room, and they were saved. The company desired that not one halfpenny more that they had lost should be awarded. They wished to make no profit as regards these stocks. Their last stocktaking was on 31 July 1920 and the stock at that time was taken at the cost price, except where the value was less than cost price by reason of certain goods having been a long time in stock. That value was £74,507. Since that date there was added stock at the cost price of £59, 626 5s 10d, which was brought up to £59, 895 11s 1d by freight and carriage charges, making a total stock of £134 402 11s 1d.

Sales in the same period and from 31 July amounted to £45,855 15s 4d. Some goods that were also on approbation at the time of the fire brought the net loss as regards stock-in-trade to £88,146 15s 9d.

In addition, the company had erected temporary buildings, but they felt that the temporary trade pursued in them would only pay its way. They estimated that there was no probability of getting a place of the magnitude of the Munster Arcade into operational order under a period of about three years. The company did not expect in substance to make any profits of the company for three years totalling £37,341 or an average roughly of £12, 447 per year. The auditors considered that the figure would be a very reasonable and moderate claim for the injury done to the business.

The company had also taken a shop at 97 St Patrick’s Street, for which they had to pay £406 subject to a yearly rental of £130 and they had to erect temporary wooden premises costing £3,500. During the cessation of work they had to pay salaries for a month, as well as paying the rent of the destroyed premises for two months.

Evidence was then presented by Patrick Barry who was a dispatch employee, Mrs Gaffney who was a housekeeper at the premises, and Finbarr McAuliffe, who was an apprentice. Mr Robert Walker was also examined. His father, Robert, was the architect of the original Munster Arcade premises and Robert (Junior) presented the original plans of the premises.

Robert had prepared a detailed estimate of the cost of re-constructing the premises as they were before. The Arcade, he said covered three-fifths of an acre, and noted that the cost to rebuild it would be £119, 742 and it would take three years to complete the work. Mr Denis Lucey, Building contractor, Denis O’Sullivan, Furniture Department, Patrick Barry on the cost of plumbing, heating, and gas fitting. John Rezin gave evidence of the value of the claim for customers goods in possession of the company at the time of the fires as well as the employee tools and personal property.

Matthew Bourke, the Recorder, ended the Munster Arcade cases and the following day gave his verdict. He deemed that some of the figures given bordered on excess and gave a compensation figure for £213,647. However, with the British government not set up to give compensation. The Munster Arcade, and the rest of the 681 claims would have to wait until after the treaty was signed in January 1922 before any movement was made on resolving compensation claims. Indeed, reconstruction only began at the Munster Arcade in 1924 it was to be in late 1926 before the new premises was finished.

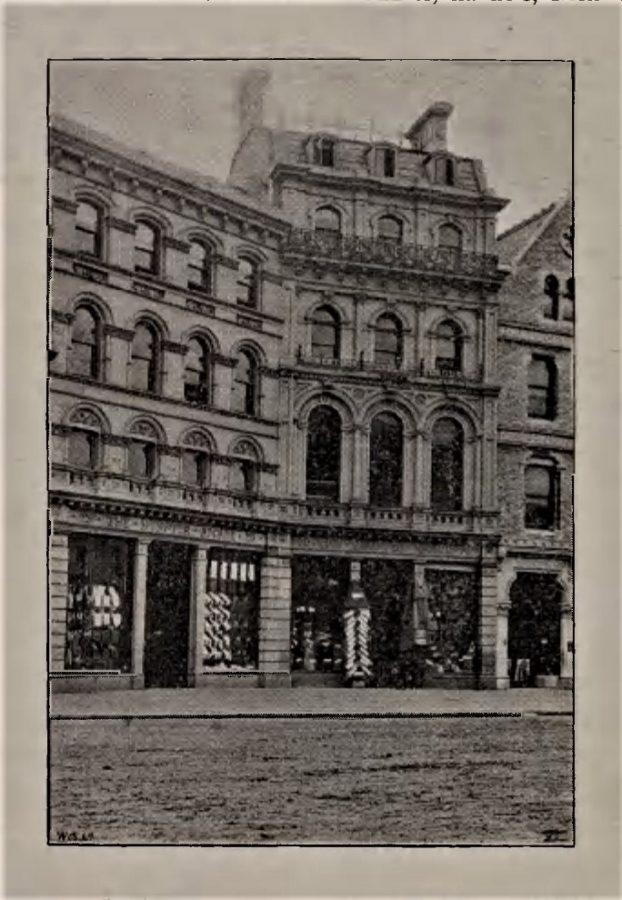

Captions:

1086a. Munster Arcade pre Burning of Cork, December 1920 from Stratten and Stratten’s Dublin, Cork, and the South of Ireland 1892 (source: Cork City Library).

1086b. The reconstructed Munster Arcade building, present day, now Penneys (picture: Kieran McCarthy).