Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 6 September 2018

Quarrying, Symbolism & Cork’s Buildings

My new book Cork in 50 Buildings aspires to celebrate some of Cork’s built heritage. The sunshine rays this summer lit up many of the city’s grey limestone and red sandstone buildings. Cork’s topography is made up of a series of alternative east-west limestone and sandstone strata. The limestone elevations of the St Anne’s Church Shandon face ‘limestone country’ to the south and west while the northern and eastern facades face traditional ‘sandstone country’. The colours of these materials have long been recognised as the colours of Cork.

Whilst researching the book, it struck me that much more research needs to be conducted on the nature of the quarries, the masons, on the architects, their work, and the symbolism they deployed on the outside and inside of buildings (much kudos to the Cork Mason’s Historical Society on their work).

Old geological studies of the city and region from the early twentieth century exist in local studies the City Library. These do offer insight into some of the quarries. The sandstone quarried had two varieties. The first and widely utilised was the Kiltorcan formation, green, grey and red at Brickfield Quarry, Sunday’s Well, and the Lee Road. A minor fine-grained sandstone was quarried at Richmond Hill and the Back Watercourse Road. The ordinary grey limestone that constitutes the chief building stone of the city, especially for public buildings was worked in numerous quarries around Ballintemple and Blackrock and at Little Island and Midleton. They were also quarried for lime burning to create fertiliser and road mending.

In 1792, when Beamish & Crawford was first established, William Beamish resided at Beaumont House, which was then a magnificent period residence situated on Beaumont Hill. During their tenure at Beaumont House the philanthropic spirit of the Beamish family was well known. The name Beaumont is the French derivative of Beamish meaning a beautiful view from the mountain or a beautiful view. The mansion house continued to have an association with the Beamish family until the 1850s. The house was eventually demolished and since 1968 Beaumont National boy’s and girl’s school (Scoil Barra Naofa) stands on its site.

In the Beamish estate, the famous 120-acre Carrigmore Quarry was opened sometime between 1830 and 1850. The particular high grade of limestone associated with this quarry meant it was widely used in the construction of quay walls, bridges, churches, banks and other public buildings within Cork City. This rock is filled with minute fossils, and these, on account of their crystalline character, weather more slowly than does the amorphous material surrounding them, and thus one gets a beautiful veined appearance.

There is quite an extensive network of caves at the eastern face of the quarry. These caves were first explored in the 1960s by the Cork Speleogical Group and a further survey was conducted by the British Cave Research group in the early 1970s. Some of the cave wall passages were found to be abundant in lower carboniferious fossil sea shells and crinoid steams.

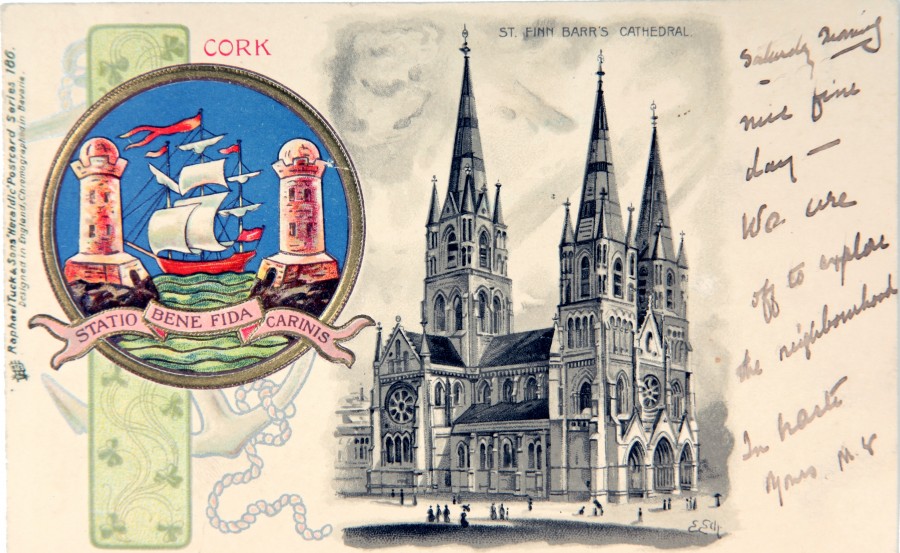

In Cork in 50 Buildings, it intentionally opens with an account of St Finbarre’s Cathedral to reflect on its myriad of stone types and symbolism. In early December 1865, the Cathedral Committee adopted limestone in place of red sandstone in the walling. Red sandstone from the Brickfield quarry in Glanmire was used for invisible walling and for the foundation while limestone quarried from Ballintemple was used in the main structure. Bath stone was used for the rest of the internal dressings. The reddish columns are of Cork red marble. Robert Walker, the appointed contractor for St Finbarre’s Cathedral visited Storeton, in Lancashire, UK, and selected the stone of that quarry for the great piers.

The architect of the present cathedral William Burges was born in London on 2 December 1827. He was the son of a successful civil engineer. He was educated at King’s College London, where he spent five years. At the age of seventeen, he entered the office of Edward Blore as a pupil where he remained for three years. Edward Blore was an avid student of medieval architecture and was involved in the design of the Houses of Parliament of the time. By the end of his time with Blore, William Burges possessed a reputable knowledge and respect for medieval architecture.

The mosaic pavement of the apse was designed by William Burges and made by Burke & Co from Lonsdale’s cartoons in Paris. It is interestingly to note that Italian artists from Udine were employed, using marble segments, reputably mined in the Pyrenees Mountains, between France and Spain.

There were 1,260 pieces of sculpture planned for the cathedral and Burges personally designed each one. Mr Nicholls modelled everyone in plaster, except for the figures in the western portals and the four Evangelistic emblems around the rose window. Everyone was also sculptured insitu by R McLeod and his staff of local stone-masons. Great care was taken to make sure that every piece was of a high standard. This was a process that was to take a decade.

Steeped in folkore, the golden angel, the gift of William Burges adorning St Finbarre’s Cathedral is also an impressive addition. Put there to make one think of the heralding of the end of the world, it also highlights the deeply rooted connection with rich ecclesiastical history on the site.

Cork in 50 Buildings (2018, Amberley Publishing) is now available from Cork bookshops.

Captions:

962a. Beaumont Quarry, present day (picture: Kieran McCarthy)

962b. Postcard of St Finbarre’s Cathedral, early twentieth century (source: Cork City Museum)

962c. Cover of Cork in 50 Buildings by Kieran McCarthy