Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 23 December 2015

Cork Harbour Memories (Part 42)

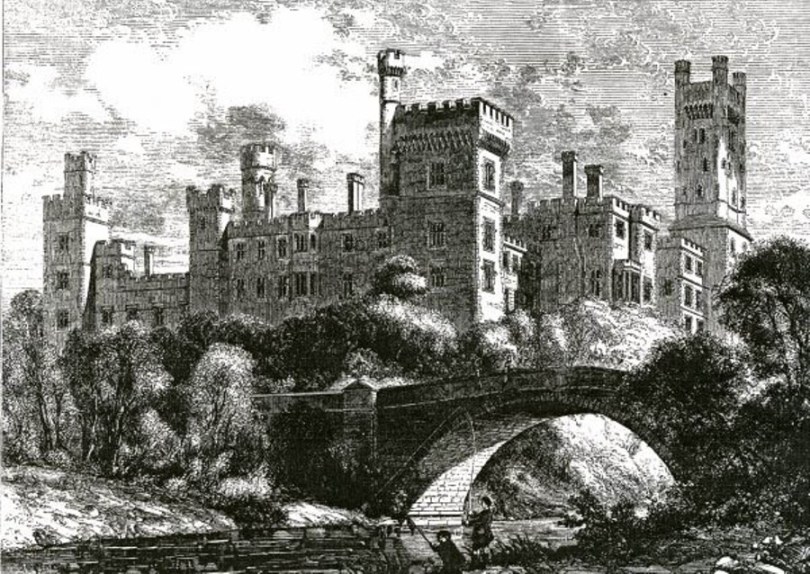

Landmark histories at Lismore Castle

The setting for the construction of the Boyle legacy was the impressive Lismore Castle and beautiful town of Lismore. A building of national importance, the castle incorporates the framework of various building projects dating primarily to the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. The National Inventory of Architectural Inventory records that the vestiges of medieval fabric in some of the towers confirming the archaeological significance of the site. The castle forms a principal landmark feature in the centre of Lismore, the range to north overlooking the broad River Blackwater. The various battlemented towers and turrets ornament the skyline and are visible from a distance.

Historical interpretative panels around the town record that the name Dungarvan is said to have originated from an old fortification to the east of the town. St Carthage is said to have founded a monastery, a celebrated seat of learning and the head of a diocese in the vicinity. Such was the fame of the place that not less than 20 churches were founded in its vicinity. In 812AD it was plundered by the Danes, who over a period till 915, ransacked the monastery five times. In the year 1095 the town was destroyed by an accidental fire, and in 1116, 1138, and 1157 both the town and the monastery suffered from fire.

The Anglo-Normans, after landing at Waterford, marched to Dungarvan and secured it by erecting a fortress for its defence in 1185. Four years afterwards it was taken by the Irish, who put Robert de Barry, the commander, and the whole of the garrison to the sword. The fortress, however, soon afterwards was rebuilt by the Anglo-Norman garrison in the area, and for many ages continued to be the residence of the bishops of the see. In 1518 McGrath, Archbishop of Cashel and Bishop of Lismore granted the manor and other lands to Sir Walter Raleigh. In time, these with the rest of Raleigh’s lands were purchased by Sir Richard Boyle. The castle was greatly strengthened and improved by Boyle, who built three other forts in the neighbourhood. Boyle also obtained a charter of incorporation for the town in 1613, and a grant for a market and fairs. The surrounding lands within a mile and a half round the parish church were made a free borough. The charter also invested the corporation with the privilege of returning two members to the Irish parliament. At the commencement of the Confederate war in 1641, the castle was besieged by a force of 5,000 Irish under Sir Richard Belling. It was defended by the Earl’s son, Lord Broghill, who compelled them to abandon the attempt.

On the death of Richard, third Earl of Burlington, and fourth Earl of Cork, the most considerable part of that nobleman’s estates, both in England and Ireland, devolved upon his daughter, Lady Charlotte Boyle. She married in 1748, William Cavendish, fourth Duke of Devonshire, in the possession of whose descendant, the present Duke, the castle now remains. The Lismore Castle papers held in the National Library of Ireland record the mid-eighteenth century estate supported a diverse range of urban and rural communities and comprised agricultural land of variable quality, about 70 per cent of it in the valleys of the rivers Bride and Blackwater in west Waterford and east Cork. This comprised considerable holdings at Lismore and the Manors of Tallow, Lisfinny, Curraglass and Mogeely, and Conna and Knockmourne in County Waterford. The remainder lay fifty miles to the west in and around Bandon, with smaller portions of Spittal lands in the south of County Tipperary and detached portions near Cork, Youghal and Dungarvan.

The present detached multiple-bay rubble stone Gothic castle at Lismore was reconstructed in 1849, on a complex quadrangular plan about a courtyard incorporating fabric of earlier rebuilding of 1812, and the original castle, 1612. The historic gardens at Lismore Castle are divided into two very different halves. The Upper Garden is a complete example of the seventeenth century walled garden first constructed by Richard Boyle, in about 1605. The outer walls and terraces remain and the plantings have changed to match the tastes of those living within the Castle. The Lower Garden was mostly created in the nineteenth century for the 6th Duke of Devonshire, Joseph Paxton’s patron. The garden is informal with shrubs, trees and lawns. The stately Yew Avenue is where Edmund Spencer is said to have written the Faerie Queen. This avenue is much older than the garden itself, probably seventeenth century.

Nearby is the impressive Saint Carthage’s Cathedral, which traces its origins back to an enclosed early monastic settlement. The present building, however, incorporates an early seventeenth-century chancel and a late seventeenth-century nave to which the tower and spire were added in 1827 by the Pain brothers George (1793-1838) and James (1779-1877). Among the treasures of the cathedral are four memorial stones dating to the ninth century; the tomb of the McGrath family (1557) with its carved figures of Saints Gregory the Great and Catherine of Alexandria amongst others; funerary monuments of Classical and Gothic design including one (ob. 1805) signed by Thomas Rickman (1776-1841) of Liverpool; and the celebrated Currey Memorial Window (1896), a pre-Raphaelite masterpiece executed by Sir Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98).

To be continued…

Happy Christmas and happy new year to all readers of the column, many thanks for the continued support.

Captions:

824a. The impressive Lismore Castle from a mid nineteenth century drawing (source: Cork City Library)

824b. The beautiful Lismore Castle Gardens, September 2015 with members of the Irish Post Medieval and Archaeology Society (picture: Kieran McCarthy)