Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 26 March 2020

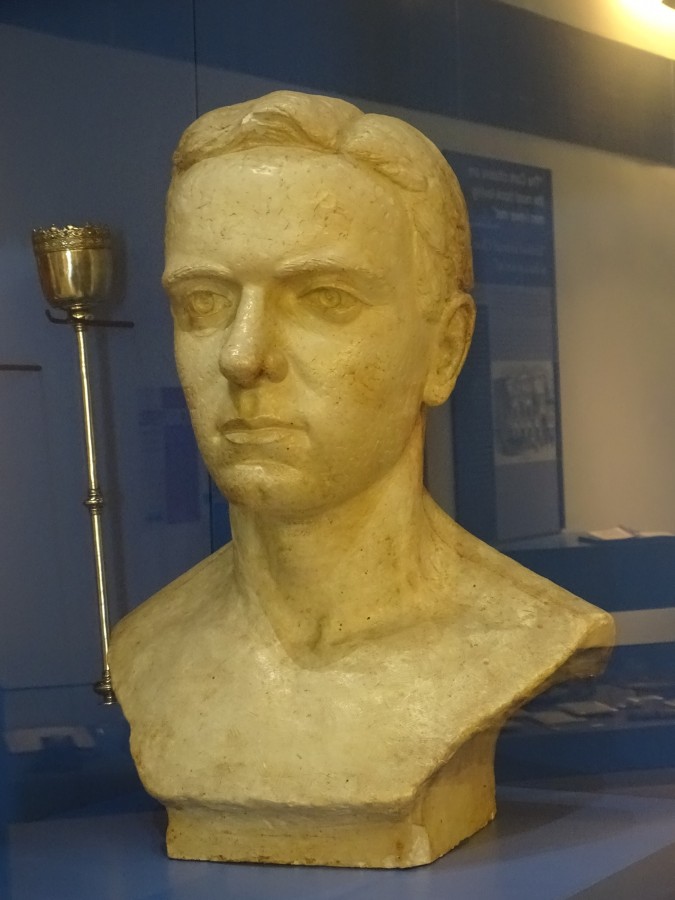

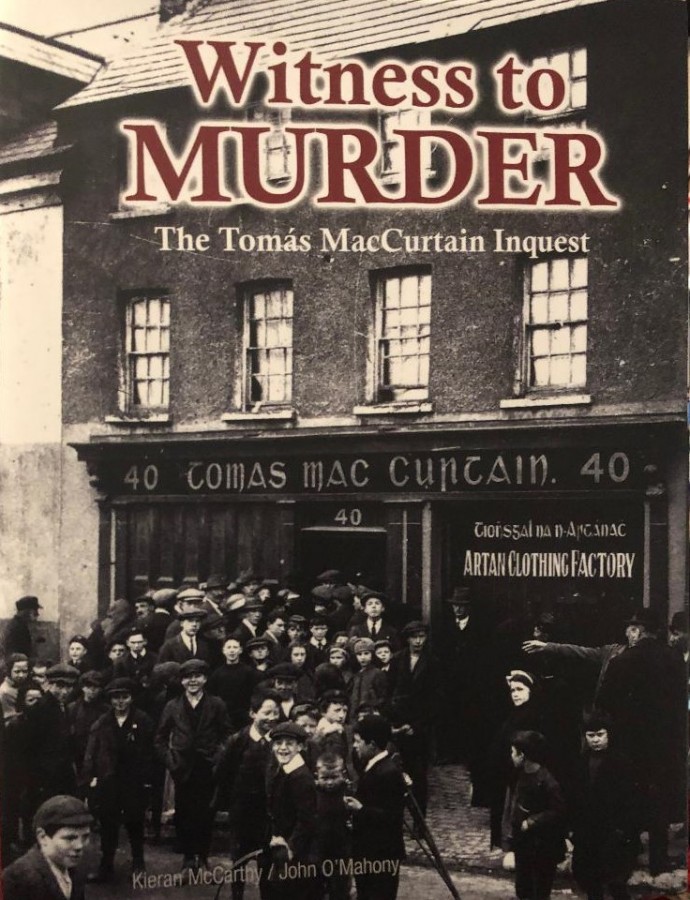

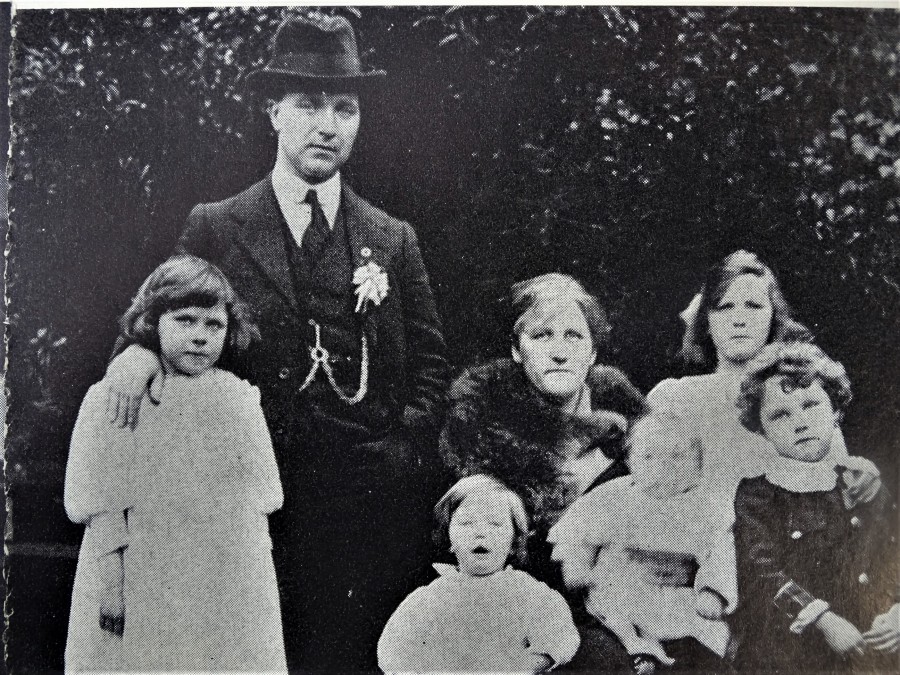

Remembering 1920: The Funeral of Tomás MacCurtain

Within just a few hours of his death in the early hours of 20 March 1920, the coffin of Lord Mayor Tomás MacCurtain was carried by hearse from his home in Blackpool to Cork City Hall. Heartrending scenes were witnessed. Men and women knelt down in the street and wept. Such was the intensity of the crowds that sections of Volunteers had considerable difficulty in managing the crowds and local traffic. The streets around Blackpool Bridge became absolutely impassable. Contingents of Sinn Féin members, members of trade and labour bodies, members of Cork Corporation and many more crammed into the area. A pipers’ band played the Dead March on the route to City Hall, and the procession of mourners, extending over two miles in length, included a large number of clergy and public men. The police were withdrawn, from the streets of the city.

Everyone wore the tricolour draped in black, and all the window blinds in the city were drawn as a mark of respect. The 1st Battalion of the Cork Volunteers acted as bodyguard, and at City Hall a party of the men remained to watch over the coffin throughout the night. The business of Cork City Hall was suspended for the removal and the funeral the following day. The Republican Flag was at half-mast above the municipal civic emblem, and on the door of entrance hall appeared, a card bearing the inscription, “Closed in consequence of the murder of Tomás MacCurtain, first Republican Lord Mayor of Cork”.

On 22 March 1920, the Celebrant of the Requiem High Mass at the North Cathedral was the Rev H J Burts CC, Rev R J O’Sullivan CC Deacon, Rev J Aherne, CC Sub-Deacon. Bishop Daniel Cohalan presided.

Upon the coffin was a plate bearing an inscription in Gaelic, translated as “Thomas MacCurtain Commandant, 1st Brigade, Cork, Army of the Irish Republic and Lord Mayor of Cork, who was foully done to death by the servants of the foreigner on March 20, 1920, in the fourth year of the Irish Republic, at the age of 37 years. MAY GOD HAVE MERCY ON HIS SOUL”.

Addressing the congregation, Bishop Cohalan put no blame on anyone but shared his condolences with the family and condemned the murder. “Every murder, dear brethren, is a violation of the fifth commandment – the murder of the humblest and poorest member of the community as well as the murder of a head of a State…we have lost the Civic Head of the municipality by the murder of Lord Mayor MacCurtain. It was an awful crime – a most unusual crime is the murder of the Mayor of a city – it was a crime against the law of God and a crime against the city”.

All national and regional Irish newspapers carried the story of the funeral. Many, such as the Cork Examiner, list the public bodies represented at the Church, which reflect the depth of respect for the Mayoralty of the city. Some of the those included the Chairman and members of the Queenstown Urban Council. Queenstown Trade and Labour and Sinn Féin organisations, Mallow Rural and Urban District Councils, Youghal, Clonakilty, Bandon and Skibbereen Councils, North-East Cork Executive Gaelic League, Southern Land Association, Cork Medical Association, and New Ross Urban Council.

Labour bodies at the funeral were: The Transport Union, Typographical Association, National Union of Railwaymen, Ford Factory employees, Bakers’ Society, Tailors’ Society, and the Grocers’ Society. Other organisations in attendance were: The Discharged and Demobilised Soldiers, Irish National Foresters, Ancient Order of Hibernians, the Catholic Young Men’s Society, Commercial Travellers’ Federation, Cattle Traders’ ‘Association, and the All-for-Ireland Club. The processionists also included the staff and students of Cork Grammar School, boys from North Monastery. Sullivan’s quay, and Blarney street Schools, and the Fire Brigade. All Creeds were represented.

The Rev Dr Dowse, Protestant Bishop of Cork, Cloyne, and Ross was represented by Rev. Dean Babington. Rev H Klein, Jewish minister and Officer of Residence, University College was also present, with Mr J T Klein, Secretary of Cork Hebrew Congregation. Mr William O’Brien, formerly leader of the All for Ireland Movement, and Captain Donelan, late Chief Whip of the Irish Party, also attended.

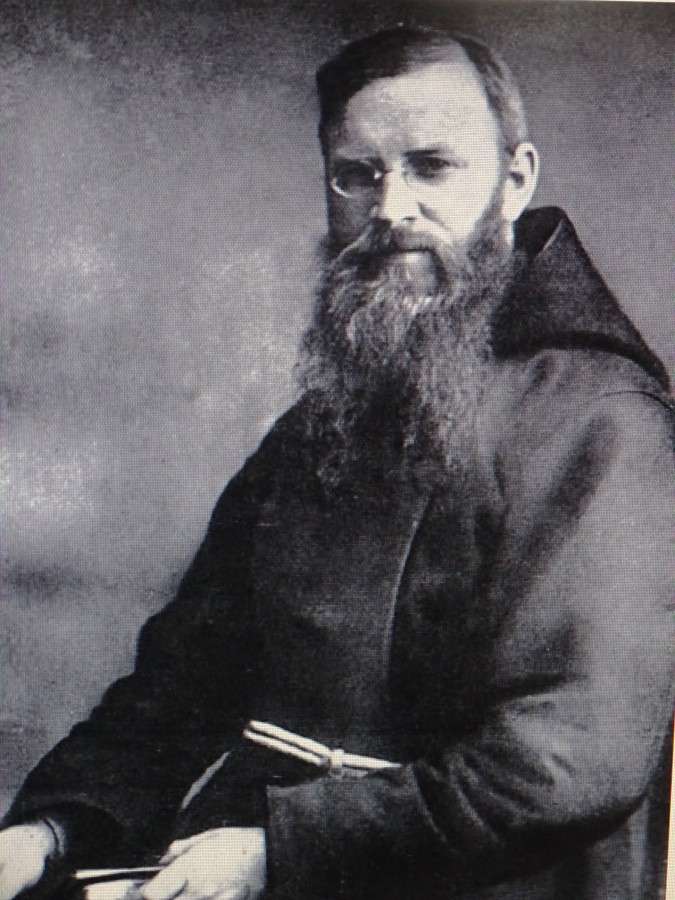

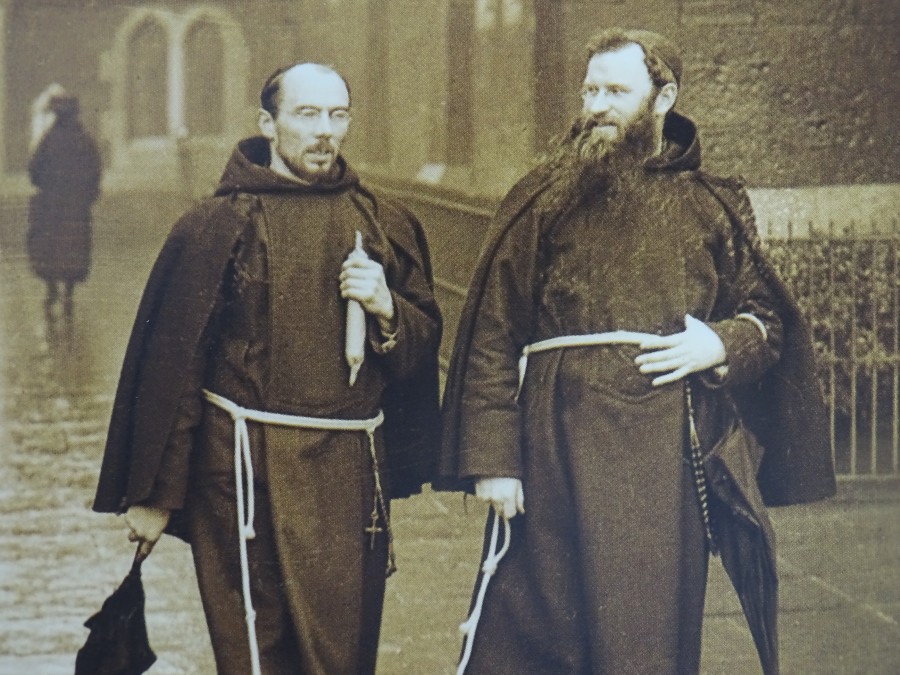

After the High Noon mass, the funeral procession started to St Finbarr’s Cemetery. The coffin was shouldered by six Volunteers in uniform. The Bishop in his carriage came next. The clergy, numbering about a hundred; Christian Brothers and presentation Brothers followed, who wore Sinn Féin mourning rosettes. Then came the Volunteers Piper’s playing “Wrap the Green Flag Round Me”. Behind was Fr Dominic who was the Lord Mayor’s Chaplain, who was accompanied by Cllr Terence MacSwiney and other officers of the volunteers. A carriage laden with wreaths followed and behind them were 25 volunteers, each carrying a wreath. Each wreath comprised an abundance of lilies and daffodils, and long flowing green, gold and white ribbons. The chief mourners walked behind, behind which was members of the Corporation, Harbour Board, and public bodies and organisation. However, the general public comprised over 10,000 people. It took one hour and a half to pass any given point.

From the North Cathedral to St Finbarr’s Cemetery, the distance was just over four miles via King Street, Merchants Quay, St Patrick’s Street, Washington Street, and Western Road. At the Western Road entrance to Cork Gaol, an open space was preserved by Volunteers to enable the political prisoners to obtain a view of the cortege as it passed from their windows.

At the cemetery, Bishop Cohalan blessed the grave. When it was covered, the Last Post was sounded and three volleys of shots were fired.

Captions:

1041a. Photo of Tomás MacCurtain Lying in State at Cork City Hall, 21 March 1920 (source: Cork City Museum).

1041b. Funeral procession of Tomás MacCurtain on Camden Quay, Cork, 22 March 1920 to St Finbarr’s Cemetery (source: Cork City Museum).