Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 20 October 2022

Journeys to a Free State: Skirmishes on the Streets

Whereby September 1922 coincided with offensive and randomly located rifle fire by Anti Treaty IRA volunteers on the National Army troops, October 1922 coincided with a step up in the type of weapon used especially using hand grenades. The Mills grenade was a traditional design; a grooved cast iron “pineapple” with a central striker held by a close hand lever and secured with a pin. The casing was grooved to make it simpler to grip. The Mills type was a defensive grenade to be thrown from behind cover at a focus in the open, wounding with fragmentation.

However, story after story, which appears in the Cork Examiner tells of warning shots more so than anything else by the IRA. However, they still shocked the general population, who tried to go about their daily business and found themselves part of tit-for-tat skirmishes on Cork City’s main streets.

A bombing of National Army troops occurred in Cork on 19 October 1922. Since the closing down of the railways owing to the destruction of local and regional bridges, a military guard was placed on duty in each station to prevent damage to rolling stock and railway property generally.

At the Cork-Bandon Railway terminus on Albert Quay, a party of 49 men were placed on duty. There were stationed at various points in the yard, but the greater number remained in the centre. At 1.15pm, an IRA volunteer came over a new bridge connecting Rockboro Road with Anglesea Street, and which ran immediately underneath the South Infirmary church and wards. After he arrived about the centre of the bridge, he flung four hand grenades in quick succession at the sentry on duty underneath. At the time, the sentry was in the engine shed, but this was not observed by the bomb-thrower.

Of the four grenades thrown only one exploded, and this was outside the shed inside, where the sentry was. The other three remained where they fell. The explosion of the single bomb while it caused consternation, fortunately did no damage, and no one was injured. The troops in other parts of the yard observed a man running towards Rockboro Road, and shots were fired at him. He, however escaped, jumping up the three steps leading from the bridge to Rockboro Road, where he had the shelter of the houses. The three unexploded grenades, which were fired at the sentry lay unexploded and were rendered harmless.

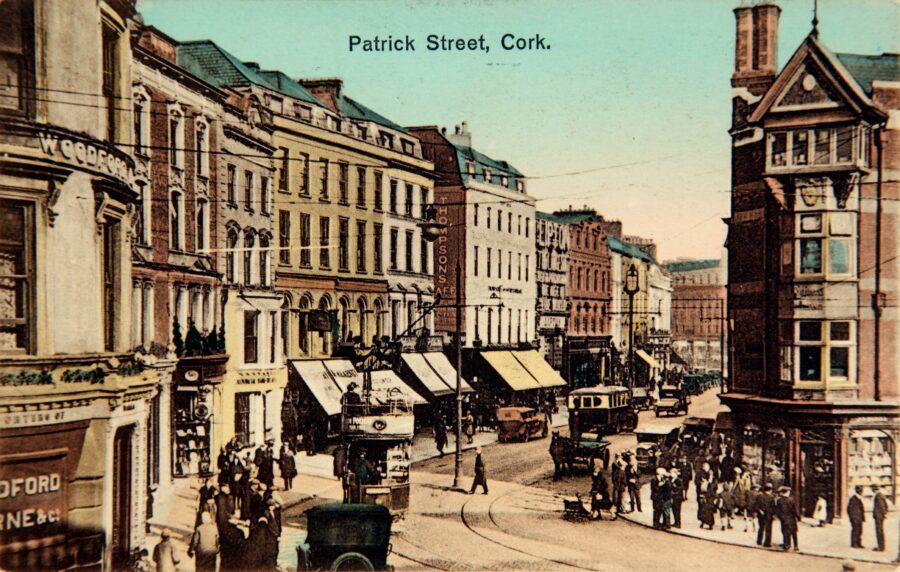

On 21 October 1922 at about 1pm a three ton lorry, containing National Army troops, was coming through St Patrick’s Street from a westerly direction, and when it had arrived in the vicinity of Messrs Thompson’s and Messrs Lipton’s, a bomb was thrown at it. It rolled a short distance after it landed before it exploded. The bomb damaged the premises of Messrs Whelan and French.

A small pony cart, which was in the vicinity at the time, was damaged. A boy named William Hornibrook was unfortunate. When the bomb was thrown, the lorry, in an endeavour to get away, struck into William’s small pony cart. The animal bolted and William’s cart was smashed into small pieces. The pony though escaped uninjured.

Others who were in the street at the times also suffered, though their injuries were fortunately of a minor nature. John O’Leary, an employee of the Macroom Railway Company, sustained an injury to the head, and he and the William – the boy – were removed to the Mercy Hospital. John has mild bruising and William suffered from shock.

The National Army troops were soon on the scene and the locality was searched, but no arrests were made. Another live grenade was found on Paul Street, which suggested that the perpetrator of the bomb escaped that way and got rid of the bomb through fear of being held up. A short time later the tram service, which was held up resumed its business.

On 22 October, at about 8.30am two lorries in convoy was on its way towards the County Gaol. When it reached the Grand Parade, it was fired on near Woodford Bourne. Several volleys were discharged from the shelter of crowds, but the troops suffered no casualties. The officer-in-charge within the National Army gave the order to his men to fire in the air, which dispersed the assailants and the general crowd very quickly. A little girl named Ms O’Donovan, aged about 13 years, was hit in the knee by some splinters. She was treated by Dr Joseph Dalton in the Mercy Hospital. About the same time snipers opened fire on several of the city’s posts, particularly at the Custom House, but return fire silenced any further hostilities.

On 30 October 1922, at 12.15pm, there was another street attack on St Patrick’s Street. The throughfare was crowded at the time. A private touring car containing three or four of the National Army was passing through the street towards the Grand Parade. They just reached Fr Mathew Statue when the attack was made.

Two bombs of the Mills’ type grenade were thrown. One was a number nine and the other number five – the number nine bomb being the larger of the two. One of the bombs struck the wooden pavement in a line with the Irish Lace House, while the second lodged on the opposite side of the street in the direction of Messrs Evans establishment. The large size bomb hit the iron work of a passing tram car – the fragments of the bomb entering the windows of the establishments of Messrs Dowden’s and Piggott’s and those of the Irish Lace House.

The passengers in the tram car were naturally terrified. One of the female occupants fainted and had to be assisted out of the car, which was not damaged to any material extent. Another female had a lucky escape when she had the heel of her boot blown completely off by a splinter of a bomb. Again, National Army troops arrived on the scene, nearby houses were searched but again no arrests were made.

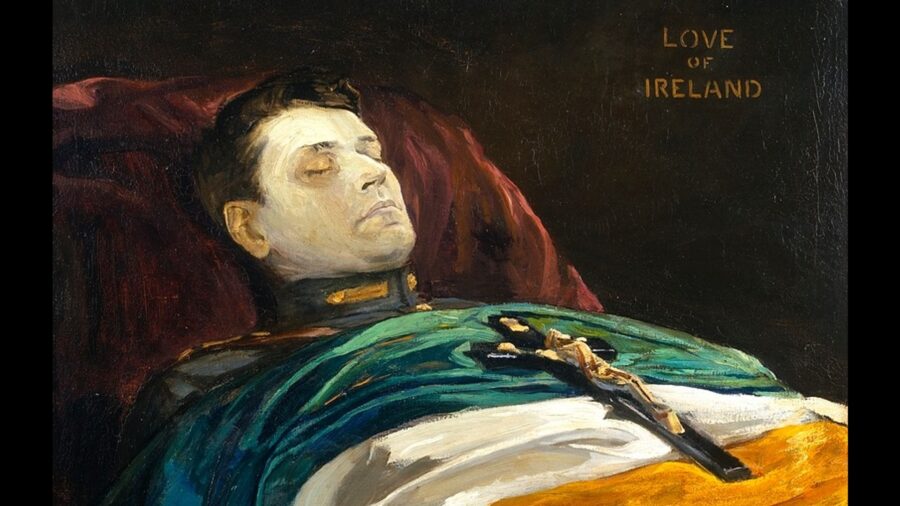

Caption:

1172a. St Patrick’s Street, c.1920 from Cork City Through Time by Kieran McCarthy and Dan Breen.