Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 6 October 2022

Journeys to a Free State: A County De-Railed

Building on last week’s column, in early autumn 1922, the Irish Civil War also happened within the satellite area of the city, where surprises attacks on National Army troops were regular by Anti-Treaty IRA members. But in particular the damage inflicted on key infrastructure points was high.

The Cork Examiner reported that on 31 August, Macloneigh Bridge, near Coolcower demesne, about two miles from Macroom was blown up by Anti-Treaty IRA members. This was the last bridge through which connection was maintained between Macroom and Cork on the south bank of the River Lee valley.

During the early hours of 2 September 1922, the Anti-Treaty IRA members blew up Dripsey bridge, and the people of Macroom area now had to come to Cork by Berrings and Cloghroe, as other bridges in the same area in the northern bank of the River Lee valley had been removed by explosives.

In early September 1922 the directors and managers of the railway services in the South of Ireland made efforts to maintain to some degree lines of communication with important centres in the country served from Cork. It was repeatedly highlighted that the wholesale destruction of railway bridges and lines was causing the unemployment of hundreds of menand inconvenience on large communities in wide agricultural districts. In early September 1922 due to damage the Cork-Macroom line had to close just beyond Ballincollig at Kilumney.

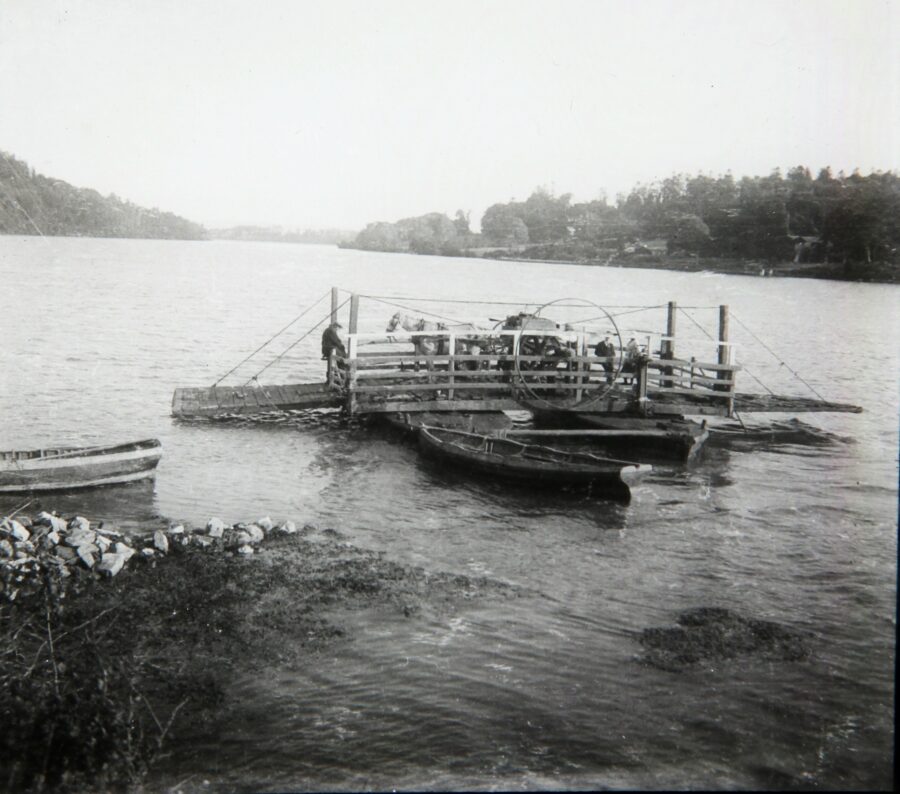

In East Cork, the loss of the East Ferry floating bridge, which was highly damaged, caused serious inconvenience to passengers and traffic from the Cobh side of the river to the Midleton and surrounding districts, where a considerable amount of communication was carried on. Rare pictures shows the bridge to be two pontoons arranged catamaran-like, decked over and fitted at either end with a landing ramp. The overall pontoon was chained-hauled between its two terminals of sorts. The bridge, which was the property of Mr Eugene McCarthy, East Ferry, was entirely constructed by him several years previous to 1922.

Using Mr McCarthy’s floating bridge locals could convoy livestock from the south of Midleton to Cove (now Cobh), at a considerably lower rate than if the stock were to be conveyed via Midleton by road. By September 1922 traffic by the latter route or road was cut off owing to the destruction of the bridge at Belvelly. The East Ferry route was the only one left. The damage to the floating pontoon to be repaired included the construction of new gangways, and the fact of the bridge had been beached after the chain was cut, caused several, leakages in the boat, and with the repairing of the chain, in all, the cost of repairs amounted to a considerable figure for Mr McCarthy.

The Cork Examiner records that on 7 September 1922 passengers on the Muskerry Railway were held at gunpoint by Anti-Treaty IRA members. Since the partial blowing up of the Leemount bridge, the railway company, for the convenience of the public ran a train from Cork to the Leemount bridge at Carrigrohane while a train was also run from Coachford and Blarney to meet it. At Leemount bridge passengers got out of the trains and crossed the bridge on foot, thus exchanging trains there. The trains then returned, one to the city and the other going on to Coachford.

About 11.30am on 7 September the train from Coachford arrived at Leemount with a large number of passengers. However, it was held up by several armed Anti-Treaty IRA members who compelled the passengers to pass between two men with revolvers for inspection. All the passengers passed through this inspection. The IRA members then removed all the mails from the train and took them across the fields towards Leemount.

On 10 September in the early morning the blowing up of the road bridge by Anti Treaty IRA members near Dunkettle station on the Great Southern and Western Railway branch line, Cork-Cobh, and Cork-Youghal. The familiar old bridge was completely blown away, all that remained were the stone piers. It was a swivel bridge, but seldom was there necessity to open it. Spanning the river stretching along to Glanmire, the only parts of the bridge left were the cylinders which are smashed and broken. It was believed that mines were laid at either end of the bridge and were set off simultaneously.

The Cork Examiner also highlighted that the destruction of the railway lines serving the southern and western coasts reduced the towns of south and West Cork, and practically all the towns of Kerry led to a large shortage of food supplies. The inland centres were even harder hit, and the enterprising shopkeepers of the towns along the coast organised alternative means of transit to the railway system. There were in all between fifty and sixty motor boats and steamers plying between Cork city and the southern and western towns and villages, including Limerick, Tralee, Kenmare, Goleen, Sneem, Cahirciveen, Skibbereen, Union Hall, Cape Clear, Sherkin Island, Schull, Castletownbere, Baltimore, Clonakiltv, Bandon and Courtmacsherry.

Ranging from ten to fifty tons, the boats brought and took the merchandise, which formerly came over the Cork, Bandon and South Coast Railway and the Kerry branch of the Great Southern and Western Railway. Cargoes from West Cork and Kerry arrived at the city’s South Jetties and included pigs, bacon, butter, eggs and fresh fish. The return cargo consisted of flour, meal, bran, groceries, salt, and the products of the local breweries and distilleries.

It is recorded that in early September twenty-five motor boats and ten steamers arrived on one day and having unloaded their cargoes of foodstuffs took with them supplies for the shopkeepers of the western County Cork towns. The boats arrived in all hours of the day and night and unloaded and re-loaded within twenty-four hours.

Caption:

1171a. Eugene McCarthy’s wooden river ferry or pontoon with horse and cart on board at East Ferry, c. 1910 from Cork Harbour Through Time by Kieran McCarthy and Dan Breen.