Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 29 March 2012

Discover Cork: Schools’ Heritage Project 2012

This year marks the tenth year of the Discover Cork: Schools’ Heritage Project co-ordinated by myself. The Project for 2012 culminated recently in two award ceremonies for the project. It is open to schools in Cork City and County- at primary level to the pupils of fourth, fifth and sixth class and at post-primary from first to sixth years. A total of 48 schools in Cork took part this year. Circa 1200 students participated in the process and approx 200 projects were submitted on all aspects of Cork’s history.

One of the key aims of the project is to allow students to explore, investigate and comment on their local history in a constructive, active and fun way. The emphasis is on the process of doing a project and learning not only about your area but also developing new personal skills. Students are challenged to devise methodologies that provide interesting ways to approach the study of their local history.

Submitted projects must be colourful, creative, have personal opinion, imagination and gain publicity. These elements form the basis of a student friendly narrative analysis approach where the students explore their project topic in an interactive way. In particular students are encouraged to attain primary material generating primary material through engaging with a number of methods such as fieldwork, interviews with local people, making models, photographing, cartoon creating, making DVDs of their area.

Students are to experiment with the overall design and plan of their projects. It attempts to bring the student to become more personal and creative in their approaches. Much of the work could be published as local heritage / history guides to people and places in the County. For example a winning class project this year focussed on the history of the city centre and mapped out their favourite shops and those older shops around them, thus connecting the past and present.

This year marks went towards making a short film or a model on projects to accompany history booklets. Submitted DVDs this year had interviews of family members to local historians to the student taking a reporter type stance on their work. Some students also chose to act out scenes from the past. A class in the city this year chose to use the style of British Pathé films and act out a scene from the War of Independence in their area and the consequences. Another group filmed moving lego characters to show a raid on a ringfort whilst others created a rap on why archaeology is important to society.

The creativity section also encourages model making. The best model trophy in general goes to the creative and realistic model. This year the best model in the city went to a set of models from Scoil Mhuire Banríon in Mayfield, which complemented their creative booklets. Indeed models of the Titanic featured this year in several projects. In the county, the top model prize went to a student who re-created the Béal the Bláth memorial with other students creating models of churches and castles as well.

Students are encouraged to compare and connect the past to their present and their immediate future. Work needs to involve re-imagining what life may have been like. One of the key foundations in the Project is about developing empathy for the past– to think about attitudes and experience in the past. Interpretation is also empowering for the student- all the time developing a better sense of the different ways in which people engage with and express a sense of place and time.

Every year, the students involved produce a section in their project books showing how they communicated their work to the wider community. It is about reaching out and gaining public praise for the student but also appraisal and further ideas. This year the most prominent source of gaining publicity was inviting parents into the classroom for an open day for viewing projects or putting displays on in local community centres and libraries. Some class projects were presented in nursing homes to engage the older generation and to attain further memories from participants. Students were also successful in putting work on local parish newsletters, newspapers and local radio stations and also presenting work in local libraries.

Overall, the Discover Cork: Schools’ Heritage Project attempts to provide the student with a hands-on and interactive activity that is all about learning not only about your local area but also about the process of learning by participating students. The project in the city is kindly funded by Cork Civic Trust (viz the help of John X. Miller), Cork City Council (viz the help of Niamh Twomey), the Heritage Council and the Evening Echo. Prizes were also provided in the 2012 season by Lifetime Lab, Lee Road (thanks to Meryvn Horgan), Sean Kelly of Lucky Meadows Equestrian Centre Watergrasshill and Cork City Gaol Heritage Centre. The county section is funded by myself and students. A full list of winners, topics and pictures of some of the project pages for 2012 can be viewed at www.corkheritage.ie and on facebook on Cork: Our City, Our Town.

Back to the Crawford Municipal Technical Institute next week…

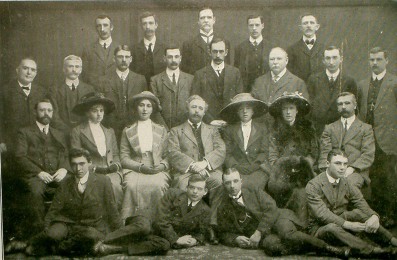

Caption:

634a. Selection of teachers and students involved in the City Edition of the Discover Cork: Schools’ Heritage Project at the recent award ceremony in Silversprings Convention Centre, Cork (picture: Yvonne Coughlan)