Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article

Cork Independent, 16 February 2012

Technical Memories (Part 6)

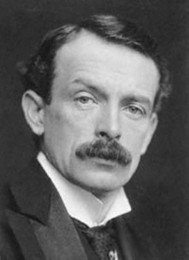

A Meeting with Lloyd George

Shortly after a technical instruction committee was formed in Cork in 1899, a deputation, who after viewing technical institute buildings in England, reported strongly in favour of constructing one in the city. The proposed structure was to house the science and technology classes and the art and craft classes being already provided for. It was not until November 1907, did the committee found its income somewhat healthy to discuss in detail a proposal for a building. It was hoped that more substantial funding would be attained from the Chancellor of the Exchequer in Westminster at the time, David Lloyd George.

On the 28 June 1908, the Irish Independent reports Dr. Bertram Windle attended a meeting with Lloyd George in London to pitch the case for extra funding for technical education in Ireland. Lloyd George had just been in this job since mid April and was hoping to introduce state financial support for the sick and infirm through raising higher taxes and reducing military expenditure. Bertram Windle was part of a deputation representing the Standing Committee on Technical Education in Ireland who was aware of the proposed financial reforms.

In introducing the deputation, John Redmond, MP for Waterford, explained that although it was a small one, it represented “universal opinion” in Ireland as to the requirements for technical education. The deputation claimed unless a grant in some way was made by the Treasury in aid of technical education, then the great deal of money already spent in Ireland would be wasted. Bertram Windle told the Chancellor that compared to Britain, Ireland had not had a satisfactory industrial past. However, he thought that anyone who visited the Franco-British Exhibition and who examined the exhibits produced under the aegis of the Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction would come to the conclusion that technicali had made great progress in Ireland.

The Exhibition, Bertram Windle referred to, was a large public fair held in London in 1908. The exhibition attracted 8 million visitors and celebrated the Entente Cordiale signed in 1904 by the United Kingdom and France. The signing of the Entente Cordiale marked the end of almost a millennium of intermittent conflict between the two nations and their predecessor states, and the formalisation of the peaceful co-existence that had existed since the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815.

The Irish work exhibited at the exhibition was as good according to Bertram Windle as that produced in English schools. The movement, he argued, was hampered in Ireland by the deficit of buildings, and he gave as examples the difficulties experienced in Cork and Kilkenny. Wexford, noted Bertram Windle, was the only place where real genuine engineering manufactories were growing, “exactly the sort of place that should be encouraged to have technical education”. He pointed out that their technical schools were carried on under adverse conditions; the extant buildings were unsanitary and unsuitable.

The argument might be used, Windle said, “why did they [government] not build suitable schools in Ireland?”. He noted that the rateable value of the country prevented it, and he compared Cork and Birmingham, the latter with a penny rate producing £6,000, while Cork only produced £700. Under existing conditions in Ireland, they must either have a school and no teachers or no teachers and an imperfect school. Ireland, Bertram Windle claimed, only wanted a fair start, and he appealed to the Chancellor for a certain sum per annum, with which they could make the technical movement in Ireland an enormous success.

Mr. E.J. Long, High Sherriff of Limerick City, pressed the points from the Limerick view, where in the previous year they had to turn away a large number of students, because of insufficient accommodation, owing to lack of funds. Mr. Forde of Belfast emphasised the claims put forward, speaking on behalf of the North of Ireland generally. If the treasury, he proposed, allocated £20,000 per annum for a term of years to technical instruction in Ireland, “the questions would be placed on a more satisfactory footing”.

The Chancellor of the Exchequer, Lloyd George, in response noted that it was not altogether accurate to say the Ireland had got nothing towards technical education prior to 1899. There was a grant in 1889 of which there was no corresponding grant to England, Scotland, or Wales. He did not wish to make a point out of that, but at the same time he could not recognise that there were arrears due to Ireland in the matter. He noted that there were many demands for investment into Ireland, demands for afforestation programmes, Congested District programmes, housing, and the Irish university question. The deputation, he told them, should not press for a final and definitive answer as all concerns were being examined at that moment in time.

The request for funding the creation of better technical colleges in the country was not met. In the Cork context, after a discussion with T.W. Russell, the Vice-President of the Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction, the Cork committee found themselves in mid 1908, in a position to ask the Corporation of Cork for a loan of £16,000.

To be continued…

Caption:

628a. Photograph of David Lloyd George, Chancellor of the British Exchequer, c.1907 (source: Cork City Library)