Kieran’s Article,

Our City, Our Town,

Cork Independent,

1 December 2011

In the Footsteps of St. Finbarre (Part 277)

Conversations in Irish Identity

“For the page has become dim. The rain has ceased. The clouds scurry from across the mountains, which are but dark outlines now. Saint Finbarr’s Lake is bright with the last reflected light. Much loath, I have lit a candle, and am, at once, as enclosed in my tiny house as a monk in his cell and all my senses reduced to one sense- hearing- the waterfalls on the hills, the flooded Lee, the sigh of the pines. A thousand years ago the hermit on the island of Gougane Bara heard the same lovely murmurings. I feel that I have travelled through time to his peace” (Seán Ó Faoláin, Sunday Independent, 18 August 1944, p.5)

It is difficult to view the extent of importance of a place like Gougane Barra and others in the evolution of ideas in shaping Irish identity. The site stands for many aspects of Irishness but also for the continuity of Irish traditions and values, all of which are also continually under attack. Travelling throughout the Lee Valley, traditions and values like in any other time, are under bombardment. In my own view their positive value or worth in society does need to be debated. Recently I came across an interesting article on Gougane Barra by Seán Ó Faoláin, which was published in 1944 in the Sunday Independent. Born in Cork as John Francis Whelan (1900-1991), as his pen name Seán Ó Faoláin he wrote his first stories in the 1920s. Through 90 stories, written over a period of 60 years, Ó Faoláin charts the development of modern Ireland. His Collected Stories were published in 1983.

Seán Ó Faoláin’s interests were broad. In his autobiography Vive Moi (1963) he was influenced by a number of themes such as the contribution of the Irish language and rural Ireland, the participation in armed struggle, and religion. They made a deep impression on him. Indeed his early work sought a new Ireland rooted in rural traditions and in the Irish language. In an interesting quote in his autobiography Vive Moi (1963, pages 141-42) he criticises the collective ambition not to have an interest in the Irish language:

“Nowadays, the learning of Irish has lost this magical power to bind hearts together. It has lost its symbolism, is no longer a mystique…today we are not in the least concerned with translating the aspirations of those days into reality…there has been a shift of ambition…the younger men…want a modernised country, prosperity, industrialisation, economic success. These ambitions have, for years, been demolishing the bridge with the past, stone by stone, until, inevitably, the Irish language, which is the keystone of the arch, will fall into the river of time. With it the life procession from the past into the present will cease”.

Ó Faoláin’s work is vast but there is a search in his work to discover the universal in the Irish experience. During his career he was as the centre of the national dialogue about what sort of nation Ireland should be. With an enormous interest in heritage, he drew his inspiration from it. He writes about all classes and professions of Irish society working class, priests, businessmen, politicians, civil servants, doctors. He aimed to show the various types of the Irish character, that these characters of Ireland are worth a study. Indeed in an attempt to understand the forces that shaped Ireland, he wrote a number of imaginative biographies of historical figures, most notably, of Hugh O’Neill and Daniel O’Connell.

In his book The Irish: A Character Study (1947), he noted that “History proper is the history of thought”. He pitched the content of the book in what successive peoples and particular events had brought to the creation of modern Ireland, and omitted the as he deemed it the “tiresome” material of histories- invasions, reigns, parliaments, dynastic risings and fallings.

One of his stories, The Silence of the Valley, is set in Gougane Barra, and appeared in his book, Teresa and other Stories. In the story, four visitors comprising an American serviceman, a practical Scotswoman, an “incorrigible Celt”, and an inspector of schools are staying at a fishing hotel in the valley. There they are being entertained by a “jolly, eccentric priest and a singing tinker”.

The visitors bring the concerns of the modern world into what Ó Faoláin notes a “rural haven”. The American wants the hotel run more efficiently. The Scot sings the praises of such “pockets of primitiveness” while enjoying “cigars and whiskey in the bar” and the Celt desires a marriage of technology and rural life. They all fish and swim in the lake but their “chatter” shows that they have a superficial awareness of their surroundings. It is the priest who first “hears” the silence when he is called away to visit an old woman whose husband, a cobbler and a renowned storyteller of the region has just died. The silence represents according to a critic of Sean’s work Pierce Butler, the presence of the past, the mystery of the unknown future, the continuity of the tradition represented by the cobbler and sensed by others- all important values that are bound up with this part of the Irish landscape.

To be continued….

Captions:

619a. Portrait of Seán Ó Faoláin, 1963 by Sean O’Sullivan

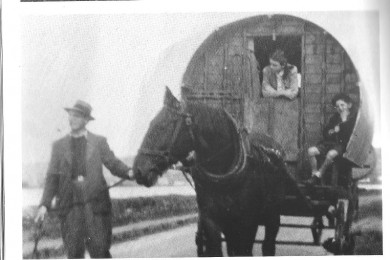

619b. Seán with family, touring West Cork in 1946 (source: Maurice Harmon’s book Seán Ó Faoláin (1994)