Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, Cork Independent, 15 July 2010

In the Footsteps of St. Finbarre (Part 220)

Fragments of Antiquity

On a beautiful view-point on the northern side of the River Lee Valley, near Cork and overlooking the approach of the River Lee to the Lee Fields, stands the jagged ruin of Currykippane (also spelt Curraghkippane), which gives name to its surrounding burial ground. Writers differ as to the origin of the placename. Many explain it as Coradh-Ceapchain, Currykippane or ‘Homestead of the Little Clearance’. In the distant past, a dense wood crowned the hillside, on which a clearance for a church or dwelling would be necessary. Other accounts attribute ‘Cora’ to the weir or ford which formerly crossed the river at the foot of the hill, and served as an approach to the ‘ceapchain ‘ or ”little clearance”. In fact, it is told that at the nearby Clogheen Calvary site during Ireland’s penal days the priest waited in secret to meet funerals on their way to Currykippane. The funeral cortege stopped and the priest recited prayers for the dead.

Of the church described “Corkapan” in 1291 A.D. little is known. Obviously, it was founded at a much earlier period, and belongs to the group of smaller pre-reformation churches and associated internments. Currykippane appears to have been restricted to families and their descendants long resident in the neighbourhood. The building appears to have needed repairs in the 1600s and reputed to be abandoned by 1693, but in 1860 only the eastern gable, some fragments of the south wall, and part of the west gable remained. The form of the perpendicular window in the chancel, as well as the stone credence in a niche in the eastern wall and a piscina in the south wall, highlight the date of the church.

Today the fragmentary remains of the rectangular church exist. Only fragments of the north and south walls survive. The west wall is now featureless and ivy-clad. The eastern wall stands tall with a narrow central window ope. The interior of the church is now crowded with burials, some recent. The earliest noted inscribed headstones in Currykippane date to 1794.

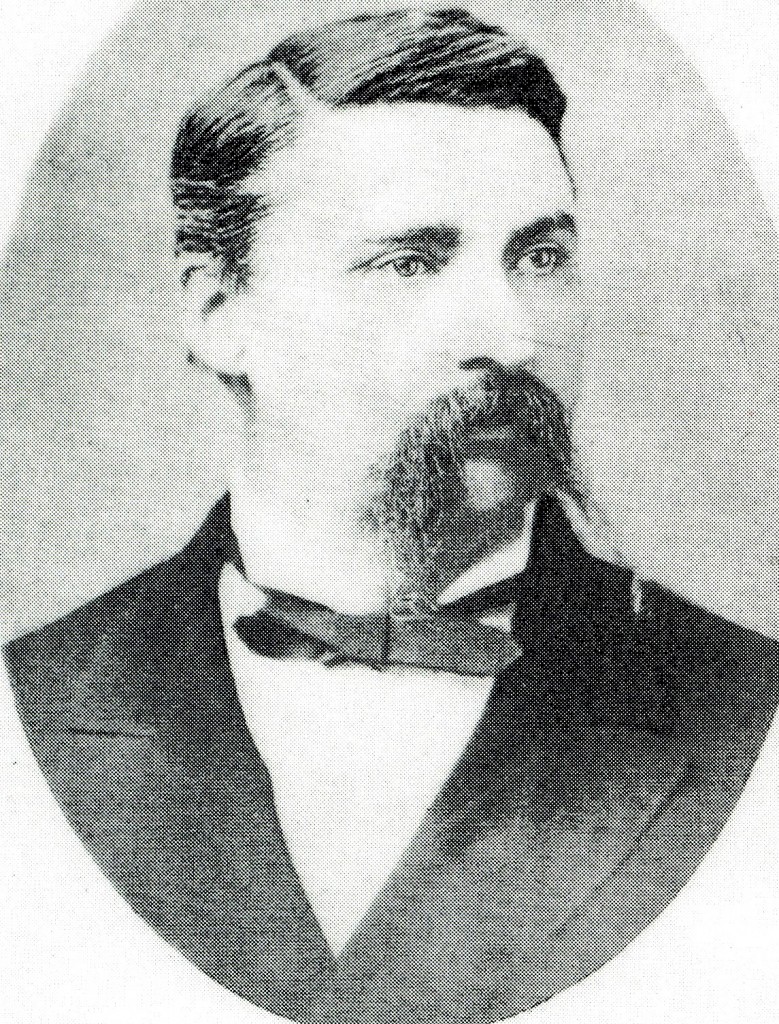

Apart from its antiquarian interest, Currykippane is revered by Corkmen as the resting place of, Jerome J. Collins, a distinguished scientist and journalist. Cork historian Ronnie Herlihy and a descendant of Jerome’s Amy Johnson have highlighted much of Jerome’s work. Jerome was born at Cork in 1841. His father, Mark Collins, was a merchant and manufacturer in the city, and a member of the Town Council for twenty-two years. At the age of sixteen young Collins became a pupil of Sir John Benson, then City and Harbour Engineer. Jerome Collins by his ability, soon became assistant engineer, and had charge of important works in the river and harbour, notably, the erection of North Gate Bridge. On emigrating to America he engaged in several important municipal works, and became Street Commissioner of Hudson City in 1869.

The, possibilities of a general weather service had a fascination for him, and. owing to his articles on the subject he became attached to the editorial staff of the New York Herald. His idea being to make collected information of practical use, and after careful experiments extending over an entire year, he began in sending the famous storm predictions for the “Herald” to Europe. Notwithstanding, the criticism of the English Press, he persevered and perfected the organization of a weather bureau. In 1878, Jerome Collins attended the Meteorological Congress in Paris, where he received high honours and contributed two papers on the rationale of storm warnings.

When Cordon Dennett organized an expedition to the North Pole, Jerome Collins became attached to the exploring party as scientist and correspondent. The Jeannnette, a steamer acquired from the British Government, left San Francisco on the 9th July 1879. In June I851, the “Jeannette” was abandoned in the icepack in northern latitudes. Two boats, however, were sound, and served in exploring for land and food. During a storm one boat with its crew became separated and both were lost. Collins, with the captain and others, secured a lauding in a desolate region, where they endured great privation. A small party went in search of food, and failed to return. Meantime, while waiting an opportunity for further expedition, the party became exhausted, and died of starvation. Commander De Long was the last to survive. His diary entry dated the 30th October 1881, states that Collins was dying by his side.

His last communication, dated 27 August 1879, from Behring’s Strait closed worryingly:

“All before us now is uncertainty, because, our movements will be governed by Circumstances over which we have-no control. We are amply supplied with fur clothing and provisions…we can go forth, trusting in God’s protection and our good fortune. —Farewell!”

Three of the party, who lost their way from camp while endeavouring to secure food, reached Siberia, where a message was sent to the United States Government. A search party was immediately dispatched from New York to join them, and after a long and hazardous search the bodies were recovered. On the 8th March 1884, the remains of Jerome J. Collins landed at Queenstown for burial in Currykippane graveyard. The funeral procession, which passed, through the streets of Cork during terrible weather was long remembered for its impressive display of public honour.

To be continued…

Captions:

548a. Ruins of Currykippane Church (picture: Kieran McCarthy)

548b. Jerome Collins (picture: Cork City Library)