Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 20 June 2024

Cork: A Potted History Selection

Cork: A Potted History is the title of my new local history book published by Amberley Press. The book is a walking trail, which can be physically pursued or you can simply follow it from your armchair. It takes a line from the city’s famous natural lake known just as The Lough across the former medieval core, ending in the historic north suburbs of Blackpool. This week is another section from the book.

A Taste of Tanora:

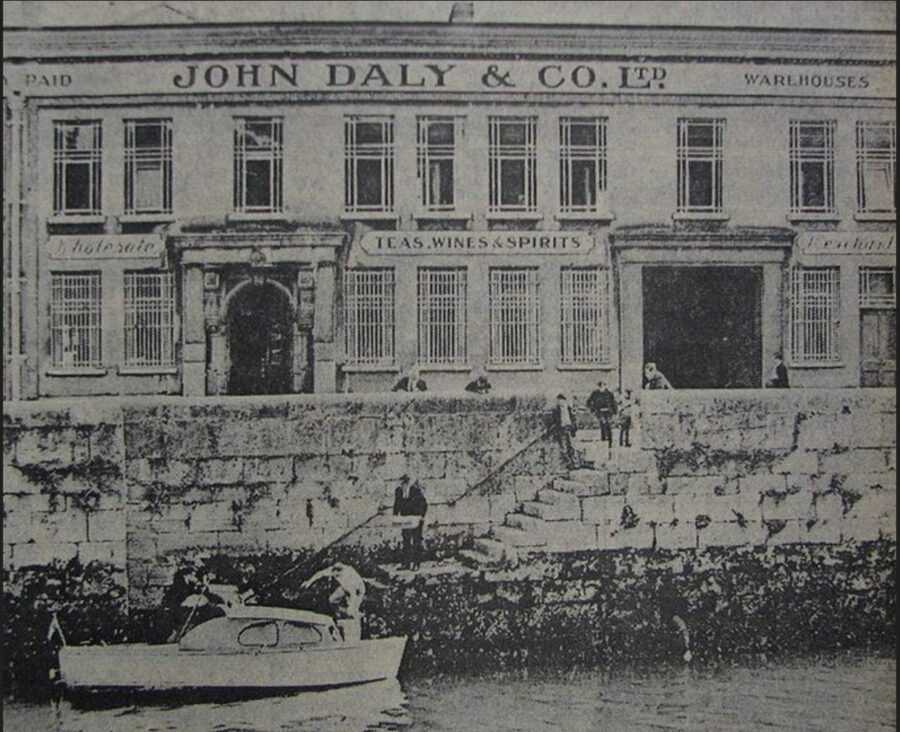

The 1779 Arch hidden behind North Gate Bridge apartments is an elegant archway with a date of 1779 inscribed on it. The archway was part of John Daly & Co. Mineral Water Manufacturers. The style suggests a late nineteenth-century, Victorian date. The 1779 archway was once part of the entrance door to the offices, one of Cork’s oldest firms reputedly established in 1779, located on Kyrl’s Quay. This was a well-established, presumably wealthy firm (later having owned the Victoria Hotel and Bonded Warehouses on Kyrl’s Quay). The status of the company and the style of the arch suggests that it was made for the Daly offices on Kyrl’s Quay.

In 1915, John Daly and Co. were also the original creators of the well-known Tanora brand – a tangerine-flavoured drink. At that time, temperance groups lobbied manufacturers of lemonade such as John Daly’s to produce another popular non-alcoholic drink. Tanora was created through the importation of tangerine oranges. Fifty years ago, Daly’s owned Kyrl’s Quay Bonded Warehouses and the Victoria Hotel in Cork.

Five decades ago, Daly’s also bought the total issued share capital of Coca-Cola Bottling (Dublin). They had the Coca-Cola franchise for Munster, which gave Daly’s extensive interests in the Irish market for soft drinks. However, it was a Munster Coca-Cola bottling company that eventually bought out the company.

The 1853 Flood and North Gate Bridge:

As the northern access route into the walled town, North Gate drawbridge was a wooden structure and annually subjected to severe winter flooding, being almost destroyed in each instance. In May 1711, agreement was reached by members of Cork Corporation of the City that North Gate Bridge be rebuilt in stone in 1712, while in 1713 South Gate Bridge would be replaced with arched stone structures.

In the opening week of November 1853, North Gate Bridge became responsible for large portions of the city being destroyed due to the high floodwaters. The London Illustrated News documented the event on 12 November 1853. The rains of Monday and Tuesday of that fateful week amounted to a total of 2½ inches. However, 5 inches had fallen in the preceding fortnight. This, coupled with a new moon, a rising tide of just over 20 feet and hurricane conditions blowing from the south-east caused the elevation of the water levels in the city’s channels.

As a result, on the Tuesday evening water started to rise at 4 p.m., and in the space of just thirty minutes the entire flat of the city was inundated. Every moment the water continued rising, higher and higher until the turn of the tide at 5 p.m.

Even though by 8 p.m. the tide had been on the ebb for three hours, the rush of water from Sunday’s Well began to rapidly increase. Water tore down the channel in torrid waves inundating the Western Road and the Mardyke, which were speedily impassable. Baths on the Western Road are noted as being carried away by a torrent Soon after 10 p.m. the rush of water at North Gate Bridge – the arches of which were very narrow – became so great that the torrent speedily overflowed its banks and bore down Great George’s Street (now Washington Street) like a river. The lower parts of the Grand Parade, George’s Street, St Patrick’s Street and all the streets and lanes in the vicinity were inundated. By 11 p.m. these streets, as well as North Main Street and South Main Street, were filled with water several feet deep.

Halfway down Lavitt’s Quay was a fountain, at the immediate edge of the river. Suddenly, a loud crash was heard, and the fountain had disappeared and around 30 feet of the quay wall had been carried away. The water, having secured another access point, rushed rapidly over the quay, overwhelming the houses. Seconds later, another portion of quay wall was torn down. On the opposite side of the river, a portion of the sewer burst and part of the quay fell in.

At 12.30 a.m., the flood, far from diminishing, was acquiring additional fury every moment. The waters were dashing under the arches of St Patrick’s Bridge carrying chairs, beams of timber, trees, etc. Suddenly a terrible crash was heard, followed by a piercing shriek. A great piece of the bridge had given way, taking with it eleven people. They were borne down with the tide and all drowned, except for one who was rescued.

Barriers of timber were immediately put into place and police and a party of military people were soon in attendance to warn folks not to cross it. A few moments later another large mass of masonry gave way and was carried into the tide. In June 1856, an Act was passed to enable the mayor, alderman and burgesses of Cork to remove certain bridges and build new ones. Subsequently, a new North Gate Bridge and St Patrick’s Bridge were reconstructed.

The foundation stone for the fourth-known North Gate Bridge was laid in April 1863. The new bridge was to be a cast-iron structure with the ironwork completed by Ranking & Co. of Liverpool. Nearly 100 years later, in 1961, the bridge would have to be reconstructed again due to increased road traffic and heavier vehicles.

Captions:

1258a. John Daly & Co. warehouses, Kyrl’s Quay, 1970s (source: Cork City Library).

1258b. Historical archway (1779) now embedded behind buildings off Kyrl’s Quay (picture: Kieran McCarthy).