Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 25 May 2023

Recasting Cork: A Visit by Jim Larkin

Exiled Jim Larkin General Secretary of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) made his return to Ireland in April 1923. Subsequently he set about touring the country meeting trade union members and appealing for an end to the Irish Civil War.

On Saturday evening 26 May 1923 Jim Larkin paid a visit to Cork. He addressed a public meeting from the windows of the old Connolly Hall on the Lower Glanmire Road. On his arrival at the railway station the well-known Labour leader was met by a large crowd and three bands – the Transport Workers’ (Connolly Memorial) Brass and Reed, the Workingmens’ Drum and Fife, and the Lee Pipers’. After he had been welcomed by Robert Day TD, Michael Hill Chairman of the Cork Executive of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union, Cllr Kenneally, and others, Jim Larkin was escorted to Connolly Hall. There a public meeting was held, which hosted a large attendance by the public.

The beginning of Jim’s career as a labour organiser dated from an earlier part of his career when he lost his post as foreman in a Liverpool shipping firm because he showed sympathy with strikers. He became an organiser for the National Union of Dock Labourers in Great Britain and Ireland. Belfast was the first Irish port in which his ability as an organiser was employed. Unskilled workers struck on a large scale for better conditions.

In 1908, following clashes between workers and employers In Dublin and Cork, Jim was instrumental in forming the ITGWU in which he occupied the position of General Secretary. The Union grew quickly and was engaged in a long and continuous series of disputes. Following the foundation of the ITGWU, he founded the Irish Women Workers’ Union and a newspaper called The Irish Worker.

From 1911 onwards the atmosphere for a bitter labour fight grew in Dublin. In 1913, William Martin Murphy, owner of the Irish Independent and controller of the then Dublin United Tramways Company, sacked despatch workers in the newspaper who belonged to the ITGWU. The strike lasted until early in 1914 and was marked by the most stirring scenes ever witnessed in Dublin labour disputes. Police baton charges were features of every meeting held by the workers and on one day alone there were 500 civilian casualties. Two workers were killed during the dispute.

When the strike ended in a sort of triumph of failure for the workers Jim Larkin went to America on a Trades Union Congress mission for funds, in 1916. As a result of his labour and pacifist attitude during the 1914-18 war he was arrested and sent to penal servitude in New York’s Sing Sing prison. Jim spent several years in prison, before he was eventually pardoned by Al Smith, Governor of New York, in 1923 and was later deported.

In Cork on 26 May 1923, Jim Larkin reminded the public that there had been a revolution in the country and the working classes should look around and see what they as workers had achieved as the result of it. Until such time as they as a class took over the political control of the country, they need not expect any favours from any government, native or foreign. He used a quote from James Connolly; “The freedom of the working class will comb only through the industrial organisation backed up by the official leaders of Labour in every legislative and governing body in the country. It was their duty to secure their emancipation”.

Giving his reflections, on the course of history, which occurred whilst he was in the US, Jim noted because he was a republican, or a “Republican before many of those who are not Republicans”. He wished to advise leaders of both sides that the time had come to keep the truce for one month, and then sit down and arrange peace terms. He wished to not ask any of them to give up their principles. He noted that some people had told him that he advised Republican supporters to surrender. He noted that that was a lie; “I would sooner die at that window gone ask any true man to surrender”.

Jim advised on what he believed that the facts must be first. The Irish Free State government was an overwhelming power; “The government had 50,000 bayonets but the people of Ireland knew that the government lived by the permission of the British Empire. Their hearts in Ireland had always been true to Cathleen Ní Houlihan, and if that were true was it not only natural that their sympathies should be with the men on the hills”. He further articulated that the power of the government was such that Republican soldiers and advisers had not the strength of arms to “win out against such power and it was the duty of the officer to save his men”.

A member of the crowd shouted to Jim a reference to the Treaty; Jim replied;“You are very good to shout about the Treaty. I am not responsible for the Treaty and no labour man is responsible for it. The labour men were not asked to go to England to talk over the treaty”.

Proceeding Jim wanted to get the country back to a “Christian point of view” where human beings would argue facts, where words would be forgotten and where principles are not personalities would be considered; “They must go on arguing. To go on fighting would never bring them anywhere. It would only weaken them”.

Jim noted that ultimately the people of Ireland had two facts to consider – the unity of Ireland and the safety of its people; “The two crimes are the partition of the country and its countrymen or killing each other…I am for the honour and glory of fighting for peace – peace by understanding and not peace at the point of the bayonet for that was the British way”.

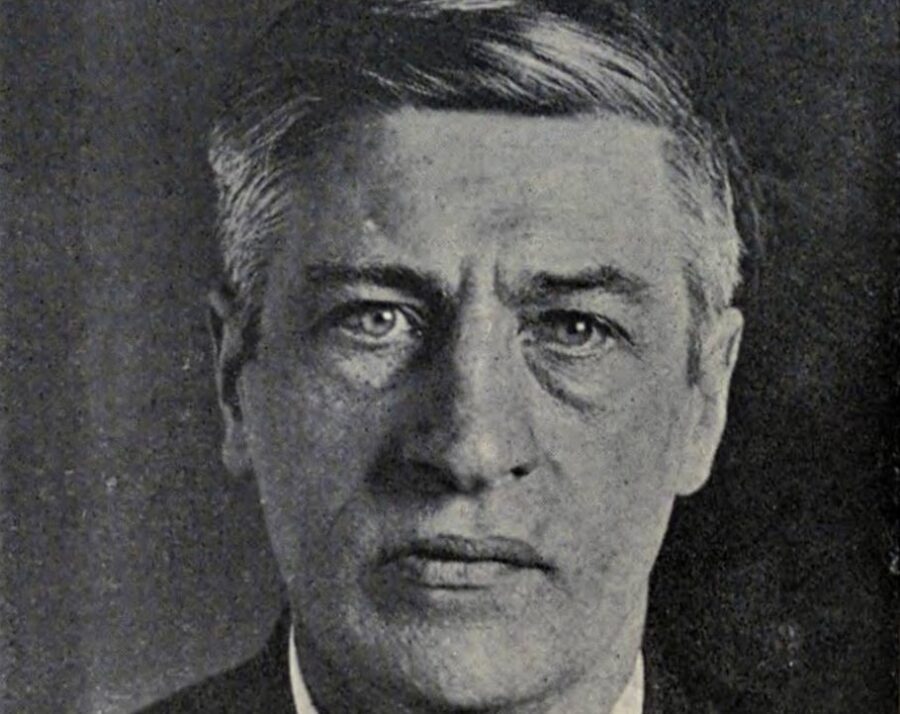

Caption:

1203a. Jim Larkin, pictured in Sing Sing Prison, New York, 1919 (picture: Cork City Library).