Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 2 February 2023

Recasting Cork: The Cork Dockers Strike

The Cork Dockers’ Strike, which began Monday 15 January 1923 and extended all the way to early February 1923, was a quest for better terms and wages within a national pay agreement for transport workers in southern Irish ports. The Cork dockers, coal, shipping carmen, and storemen sections of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union, took a ballot on the proposed national pay deal reduction of 1s per day for full time workers and a pro rata reduction for tonnage workers.

Over a 1,000 Cork dockers picketed operations that were being carried out on Cork City’s quays. The scheduled sailings of the cross-channel boats were cancelled. Trade was diverted from the port of Cork. In particular heavy losses by those involved in the cattle trade began. In the immediate few days after the strike was called, a consignment of 750 mixed cattle awaited shipment for Birkenhead, UK. The consignees estimated that the loss of the non-sailing of one steamer called the SS Classic on the Birkenhead route at £1 per head, through loss of markets and deterioration of meat.

By an arrangement entered into with the strike committee the unloading of three vessels with cargoes of flour was allowed to proceed, as was also the discharge of the steamer Benwood from Derry with potatoes. A strong guard of national troops patrolled Penrose Quay, and only persons on business were permitted to pass in the direction of the shipping companies’ premises.

Apart from the jobs of dockers, many more connected jobs and firms were also affected. The Cork Examiner on 18 January 1923 outlines that between the south and north channels, there were close on a dozen steamers of good average tonnage tied up, with cargoes awaiting discharge. Permits were granted for the loading of a few vessels during the day. These goods mainly comprised of flour.

The deadlock created many difficulties for local firms. For example, the practice of the Metropole Steam Laundry, Lower Road, and the practice of the company to draw their own coal supplies for the use of the laundry, resulted in the laundry shutting and one hundred employees being laid off.

The Greenboat goods service conducted by the Cork, Blackrock and Passage Railway Company was not allowed run. Since the damage and enforced cessation of railway facilities the service had proved to be of great benefit to the residents of the lower harbour. Even though, the crew were members of the National Union of Railwaymen, they had no differences with their employers.

Another ship, the Lady Kerry was undischarged and was unable to resume her outward sailing. However, the work of taking off her 175 sacks of mails was undertaken by national troops and the sacks were conveyed under escort to the Cork GPO.

On 19 January 1923, whilst there was no national troops patrol in the vicinity, a Fordson motor lorry conveying Mr Edward Grace, the manager of the extensive Ford Works on South Docks, went to the point where the SS Glengarriff was berthed to collect one of his employee’s personal possessions. Mr Grace, on alighting from the motor lorry, was at once surrounded by a strong picket of the strikers, and the drivers of the lorry was meanwhile threatened against assisting in the removal of any goods from the steamer.

A very heated an animated discussion ensued. In defiance of the anger around him, Edward Grace forced his way onto the gangway of the vessel. After an interval of about 15 minutes, he reappeared on the gangway with a bag of soft goods on his shoulder.

Proceeding to leave the vessel, Mr Grace was held up when midway up the gangway missiles were thrown at him. He immediately took out a revolver and pointed the weapon at the strikers. The strikers maintained possession of the gangway and prevented him from coming ashore.

In the meanwhile the driver of Mr Grace’s motor lorry drove off in the direction of Railway Street, with the aim of getting national troops assistance, but was outmanoeuvred by a section of the crowd. They brought the vehicle to a standstill in Alfred Street, where it was set on fire.

Mr Grace was eventually permitted to leave the vessel and sought refuge in one of the offices of the City of Cork Steam Packet Company stores. National troop soldiers came on the scene and Mr Grace was escorted from the quays.

Tensions remained heightened throughout the strike negotiation talks. On 22 January 1923, a conference between employers and docker representatives were held at the Cork Employer’s Federation at the South Mall. The conference was initiated by the Cork Workers’ Council and Fr Thomas Dowling (before he left for America; see last week’s article). The officials of the Workers’ Council who were present suggested some arrangement might be arranged whereby work could be resumed pending further conferences on the National pay deal for dockers and that such terms would not apply to Cork. The proposals were not responded to at first by the Ministry of Labour within central government, which left the strike ongoing until 1 February.

On 1 February in the offices of the Ministry of Labour in Dublin’s Edward Street, Irish Ship owners and the Irish Trade and General Workers Union struck an agreement on the restoration of the reduction of one shilling per day and the restoration of the pro rata reduction for tonnage workers.

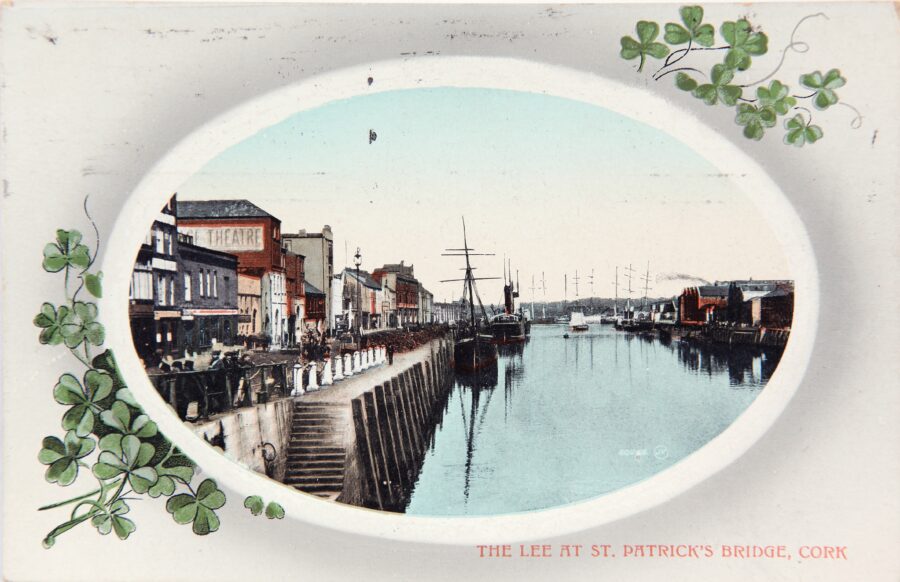

Caption:

1187a. View from St Patrick’s Bridge of St Patrick’s Quay and the North Channel of the River Lee, c.1900, from Cork City Through Time by Kieran McCarthy and Dan Breen.