Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 9 September 2021

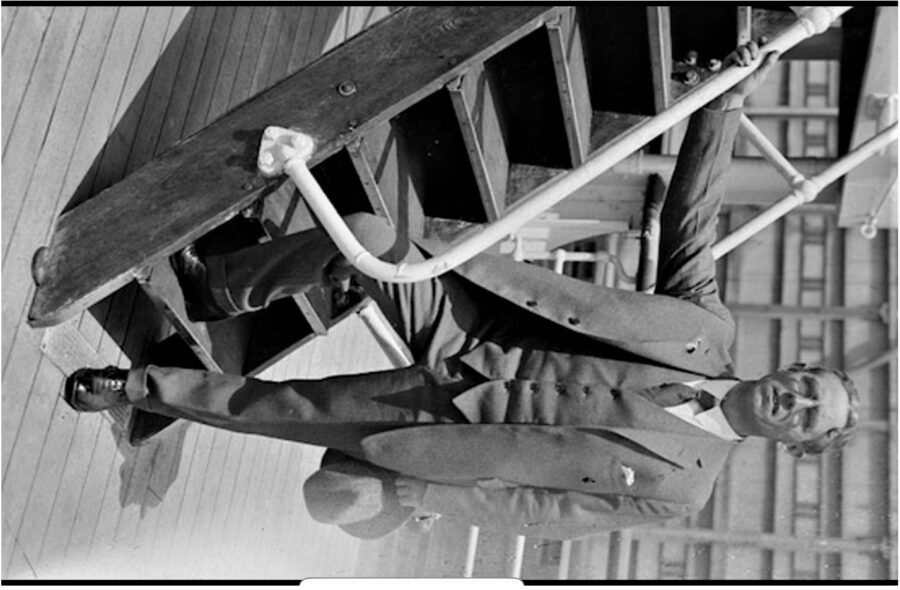

Journeys to a Truce: Fawsitt and Opportunities in the US

One hundred years ago this week, Corkman Diarmuid Fawsitt outlined his work to the Irish general public as Ireland’s American consul. He had just stepped down from the role and had begun working with Éamon de Valera on creating an economic set of requirements to be bedded into the early negotiations on the Anglo-Irish Treaty.

An obituary on 5 April 1967, published in the Cork Examiner records, Diarmuid was born near Blarney Street in Cork’s northside in 1884. Diarmuid was active in cultural, industrial and nationalist circles, including the Celtic Literary Society, Sinn Féin, the Gaelic League, Cork National Theatre Society, and especially the Cork Industrial Development Association (IDA). Diarmuid established the Cork IDA in 1903.

Coinciding with Diarmuid’s strong lobbying of the British government, in November 1913 Diarmuid attended the inaugural meeting of the Irish Volunteers in Dublin and was inducted into the Irish Republican Brotherhood. In December 1913 he was one of the co-founders of the Cork Corps of the Irish Volunteers at Cork City Hall, later becoming Chairperson of the Executive. In November 1919, Arthur Griffith sent Diarmuid to the United States as consul and trade commissioner of the Irish Republic. He was based in New York until late August 1921 and built up a staff of nine.

In what looks like a carefully-crafted type standard press release and then a series of follow-up interviews in early September 1921 with Ireland’s regional newspapers, Diarmuid outlines his near two-year work as American consul. On arrival in the US, Diarmuid formally notified the American government of his presence and commission. Diarmuid was regularly in touch with and helped by the US government departments and was never interfered with in this work of enlightening American businesses that Ireland was a land of great possibilities.

Diarmuid highlights that one of the early difficulties encountered by the consulate was that interested American houses in direct Irish trading included Ireland in the territory of British commerce – apparently thinking it, as Diarmuid quote, “was just like an English Shire” and that those interested had not heard of existing and emerging industries in Ireland.

The educational work carried on by the consulate such as advertising Ireland’s markets in American trade journals was crucial to correct any misunderstanding and to create opportunities. Presentations were made before chambers of commerce and trade organisations in different US cities and personal contact was made with exporters in the United States. The Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce in the US regularly corresponded with Diarmuid and placed the facilities of their Daily Bulletin at his disposal to advertise the specific requirements of Irish firms. Diarmuid notes: “If America offers better prices we will sell to her rather than England”.

Diarmuid cites that several United States banks availed of the services of the consulate to obtain reliable data on the financial condition of Irish industries – especially those seeking connections to American chambers of commerce and merchant associations.

Diarmuid was also instrumental in securing a direct freight service and having cargo facilities on the passenger boats made available for the transport of high-class freight requiring refrigeration in transit. The latter was of huge importance in connection with the shipping of perishable produce such as butter and eggs in the absence of such facilities.

With regard to Irish produce Diarmuid outlines that he sat in conference with the horticultural board in Washington on one occasion. There he made a successful application to lift an embargo which the Department of Agriculture had placed in 1912 on Irish potatoes entering the United States markets. Up to that year Ireland had pursued a large trade in potatoes with the US. Since that year no Irish potatoes had been admitted into the American markets.

Dealing specifically with the interest of the fish trade Diarmuid notes that in February 1921 it was proposed to put a tariff on cured fish entering the US. He appeared personally before the relevant committee of the House of Congress to set out fully the position of Irish fish exports. As a result of the emergency tariff passed by Congress on that occasion it did not contain any tariffs on cured fish.

In numerous incidences the consulate secured direct representation in Ireland for American business houses. The consequence had been that the non-direct trade between the two countries had shown an increase of upwards of 50% in 1921 year compared to the preceding one of 1920. A great deal of trade and money that otherwise would have passed to England and English agents was diverted directly to Irish businesses.

Diarmuid notes that the consulate was in receipt of numerous applications from firms throughout America desirous of securing supplies of Irish products – describing – “I am satisfied that the work of the consulate will bear results that will greatly strengthen the commercial and sentimental ties that at present bind the Irish and American peoples”.

Diarmuid in speaking on some of his general consular work in the US said it also included the suitable protection of the interest of Irish Nationals in America and attending to the interest of Irish immigrants arriving at American ports. Immigrants with the permit or passport of Dáil Éireann who sought assistance of the consulate were helped to find employment. The consulate was also regularly consulted by Americans as well as Irish nationals on questions concerning properties and disputes in Ireland. In addition, the consulate also validated legal documents for submission to the Irish courts and formulated passports for Americans about to travel in Ireland.

Captions:

1116a. Diarmuid Fawsitt, c.1921 (picture: Department of Foreign Affairs, Dublin).