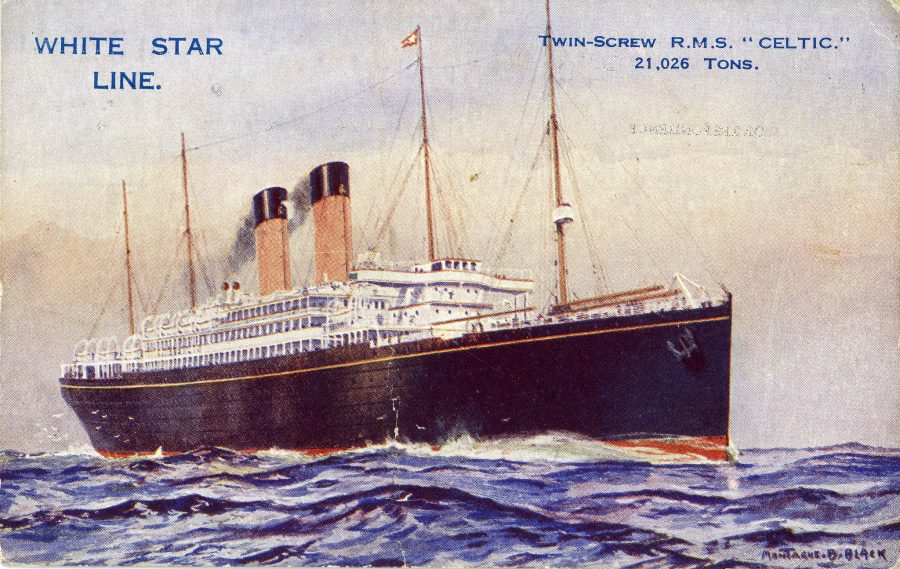

1054a. Postcard of RMS Celtic, 1920 (source: Cork City Library).

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 25 June 2020

Remembering 1920: The Return of the White Star Line

In the summer of 1920 there was much excitement at the resumption of the call to Queenstown (now Cobh) by the White Star Line and their America to Europe line of ships. The connection to Queenstown had been broken since 1907. In late April 1920 the ships RMS Celtic and RMS Baltic were scheduled by the White Star Line to arrive at Queenstown on the outward bound route to New York, from 3 June to 23 September 1920.

The linkage to such a prominent liner company and its heritage was important for Cork and the country. In 1845, John Pilkington and Henry Wilson in Liverpool established the first company displaying the name White Star Line. It concentrated on the UK–Australia trade, which grew subsequent to the discovery of gold in Australia. In 1871 White Star began their journey across the North Atlantic between Liverpool and New York (via Queenstown) developing six nearly identical ships, known as the ‘Oceanic’ class.

The White Star Line is more famous for its losses more so for what its passenger liners achieved. These included the wrecking of the RMS Atlantic at Halifax in 1873, the sinking of RMS Republic off Nantucket in 1909, the loss of the RMS Titanic in 1912 and the RMS Brittanic in 1916 while serving as a hospital ship. However, the company retained a prominent hold on shipping markets around the globe before falling into decline during the Great Depression, which ultimately led to a merger with its chief rival, Cunard Line. The Cunard-White Line lasted until 1950.

The RMS Celtic was an impressive liner, which was built at Harland & Wolfe in Belfast in 1901 and was over 21,000 gross tons in weight. Leaving New York on 15 May 1920 the liner was bound for Liverpool with a stop at Queenstown. Over a week later on 23 May 1920, “Celtic Abreast” was the radio message received at the White Star Wharf in Queenstown. The Cork Examiner records that the Clyde Shipping Company’s tender Ireland cast off about 3.30pm from Queenstown and proceeded out the harbour to await the liner coming along the coast from the Old Head of Kinsale.

Approaching Spike Point those on the tender could see that a thick fog was coming in as Roche’s Point was approached. But this was where Pilot James O’Donovan was taken on board. Locating the RMS Celtic would not be an easy matter. After a time the tender began to steer due south towards Daunt’s Lightship. Before reaching she blew her siren to alert the RMS Celtic. There was no sign of the liner in any direction. The fog at this time, was very dense, and appeared to be much more so further out.

The lonely lightship Fulmar, which marked Daunt’s Rock, ten miles south of Queenstown loomed up out of the fog and a megaphone message to the crew on board brought the disheartening response: “Yesabout half an hour ago, we heard her siren going it seemed to be coming from about two miles astern, and the ship sounded as if travelling to the eastward”.

This dispelled all hope of the RMS Celtic stopping to land the 380 passengers due to disembark at Queenstown and after a short interval the tender’s bow was put towards Scot’s Wharf at Queenstown – a town which was decked with flags to celebrate the beatification of Oliver Plunkett at the time. It was estimated that the fog cost the town a loss of £1,000 – the loss being to the hotels, boarding houses.

The RMS Celtic made for Liverpool where passengers for Queenstown and Ireland were transferred and sent via Holyhead to Dublin. On 26 May 1920 they arrived at Dublin’s North Wall just in time to meet the Railwaymen’s strike arising out of refusal to carry British munitions to meet the ongoing War of Independence. The strikers downed tools and left the passengers’ luggage buried deep in the hold of the Dublin-Holyhead ship the Curraghmore. The Americans were kept all day at North Wall Station, where they sat surrounded by cabin boxes and light luggage until the evening train to came to move the heavy goods from wall.

On 3 June 1920, the RMS Celtic arrived to Cork Harbour again bound for New York. This time the tender did connect with her. Upwards of 500 people wished to travel on the steamer. One of the noted passengers on board was merchant and yachtsman Thomas Lipton, who was presented with a series of addresses of presentations by Crosshaven yacht Club and Cove Sailing Club. Thomas Lipton was a Scotsman with Irish parentage. He pursued broad advertising for his chain of grocery stores and his brand of Lipton teas. As a keen yachtsman between 1899 and 1930 he challenged five times the American holders of the America’s Cup through the Royal Ulster Yacht Club. His yachts were named Shamrock through to Shamrock V. His endeavours met with failure but were so well-publicised that his tea became famous in the United States and made the cover of Time magazine in November 1924.

Cork Harbour as a call location for the RMS Celtic lasted for 8 years till her dashing off the rocks adjacent Roches Point on 10 December 1928 by a southerly gale. Her two hundred and sixty-six passengers were placed on tenders and landed at Queenstown at noon. At low tide the RMS Celtic was virtually high and dry about thirty yards from Calf Rock, hump of rock, and lying parallel to the mainland, three hundred yards distant.

Kieran’s new book Witness to Murder, The Inquest of Tomás MacCurtain is now available to purchase online (co-authored with John O’Mahony 2020, Irish Examiner/ www.examiner.ie).

Captions:

1054a. Postcard of RMS Celtic, 1920 (source: Cork City Library).

1054b. White Star Wharf at Queenstown (now Cobh), c.1910 (source: Cork Harbour Through Time by Kieran McCarthy, Dan Breen & Cork Public Museum).

1054b. White Star Wharf at Queenstown (now Cobh), c.1910 (source: Cork Harbour Through Time by Kieran McCarthy, Dan Breen & Cork Public Museum).