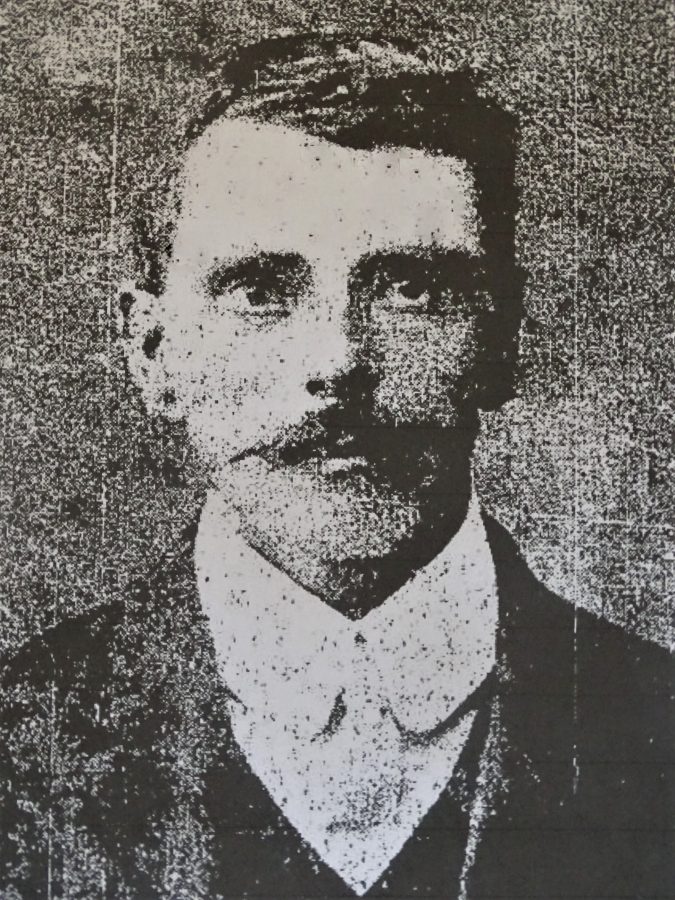

This week, Cork remembers the centenary of martyred Lord Mayor Terence MacSwiney. A colossus in Cork history Terence has attracted many historians, enthusiasts and champions to tell his story. His story is peppered with several aspects – amongst those that shine out are his love of his family, city, country, social bonds, language, comradeship, and hope – all mixed with pure tragedy.

In many ways, the end of his 74 day hunger strike changed the future public and collective memory narrative of Cork history forever. Each generation since his death has marked his contribution, reflected on its history, and have made sure that his memory will not be forgotten about and that his legacy will live on.

In our time, never before have ideas such as social bonds, family, comradeship and hope being so important as we journey through our challenging COVID times. There is much to learn from Cork 100 years ago and from some of the positive characteristics of society that imbued such a time.

One aspect, which is most welcome in 2020, is the continuous local history writing of new angles on the lives and experiences of those involved with the Independence struggle. The city is blessed with historians who spend each year retelling the story of the war but who also go out into communities and local schools, refreshing the stories amongst the older community and engaging the next generation.

Such latter scholars are also pushing for more scholarship on the time. There is still much work to be done in mining into Terence’s key works, his writings, perceptions and learning from his legacy. His book Principles of Freedom inspired many to rise up against British control in the late 1920s and 1930s. He was also a playwright, poet, founder of the Cork Dramatic Society with another of Cork’s famous literary sons Daniel Corkery. Terence wrote five plays with themes around revolution, democracy and freedom. Terence McSwiney was also a son, a husband, a father and a brother. The journey his relatives had to go through during his hunger strike also need to be explored more. The story of his sisters and their involvement in the local Cumann na mBan with the Cork Cumann’s story being told more and more, and this is most welcome.

Terence was also a proud Corkonian. His speech, when elected Lord Mayor on 30 March 1920, made reference to Cork’s place as one of Ireland’s first cities – indeed his call to work together for Cork’s advancement is one, which transcends every Corkonian generation and ever more important in the times we find ourselves in the at the moment; “Our spirit is but to be a more lively manifestation of the spirit in which we began the year to work for the city in a new zeal…to bring by our administration of the city glory to our allegiance, and by working for our city’s advancement with constancy in all honourable ways in her new dignity as one of the first cities of Ireland, to work for, and, if need be, to die for”.

I have been blogging about the centenary of the War of Independence in Cork in 1920 on my website at www.corkheritage.ie, which contains links to my newspaper articles and pictures. My work attempts to provide context to this pivotal year in Cork’s history. My blog pieces also explores Cork in 1920 and how the cityscape was rapidly becoming a war zone. Risky manoeuvres by the IRA created even riskier manoeuvres as ultimately the IRA took the war to the RIC and Black and Tans. Reading through local newspapers each day for 1920 shows the boiling frustration between all sides of the growing conflict. Tit-for-tat violence became common place.

Earlier this year I released a new book Witness to Murder, The Inquest of Tomás MacCurtain with John O’Mahony. The last time Tomás’s inquest in full was published was in the Cork Examiner between 23 March 1920 and 18 April 1920. Despite the ordeal and daily fallout from the interviews, over time the fourteen hearing sessions have not overly been revisited by scholars of the Irish War of Independence. The verdict has been highlighted on many occasions by many historians, but the information of the inquest has never been overly written about or the narratives within it explored.

What I have learned so far through my journey trying to understand the War of Independence in Cork is that the narrative is not black and white – it’s not a full on “them versus us” narrative – but very nuanced with all those involved living in a small city, where everyone knew each other – where harsh decisions on life and death needed to be made.

The public commemoration of the centenary of Terence MacSwiney may be lessened due to COVID this year. But there is an onus on all those who have championed his story to reflect this week on his sacrifice and also on the men and women, who fought for Irish Independence one hundred years ago. Many put their lives on the line and many were killed for what they believed in. Each one of their stories is an important one. Terence and Tomás MacCurtain may be the duo who annually receive much attention in our city but I have seen through my engagement in local communities the many War of Independence medals in personal collections, which are treasured, and the many stories still waiting to be told. There is still much work to do to try to understand Cork and Ireland of 1920, which defined how Cork and indeed Ireland approaches its national history narrative in the present day and going into the future.

The voices of those who were on the frontline of the War of Independence must not be forgotten but learned from – they all add up to the sense of pride amongst its public have but also to the many complexities and nuances of the history of our southern capital, and what makes it lovingly tick – with all its positives and ongoing challenges.

Cllr Kieran McCarthy is a local historian and is an Independent member of Cork City Council. His heritage website is www.corkheritge.ie