Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 16 November 2017

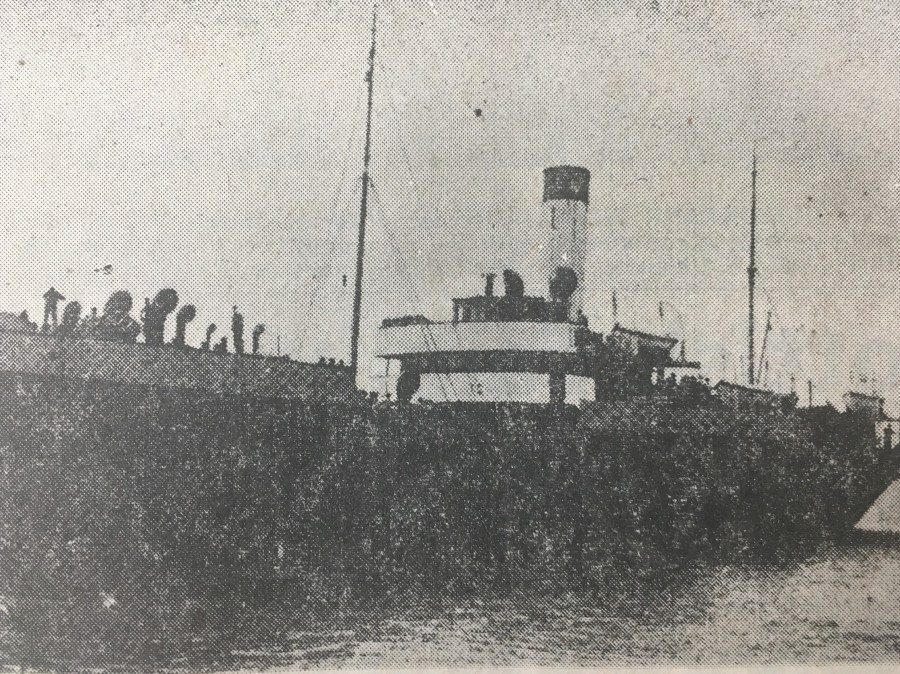

The Wheels of 1917: The Demise of the SS Ardmore

This week, one hundred years ago, the Cork cargo steamer SS Ardmore was attacked and sank without warning at 10.30pm on Tuesday night, 13 November 1917. In an account of the History of Port of Cork Steam Navigation by William J Barry in the Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society (1918) he relates the SS Ardmore made her maiden voyage from London to Cork in 1909 and kept sailing on that line, even after the start of World War I. The ship had carried men during the war to the French coast. She had a stationary crew of 27 and was under the command of Captain Richard Murray.

The SS Ardmore left London and set sail for Cork on 13 November 1917 with her crew of 27 and general cargo onboard. The chief engineer of the ship on this trip was Michael J O’Sullivan, three of whose brothers were also steamship engineers. He was not permanently attached to the SS Ardmore but an event necessitated Michael remaining ashore for some days. That caused a transfer of another engineer officer to his former ship, and he being again fit for duty, was posted to the SS Ardmore on her voyage.

Before the ship left London, her crew were told to be extra careful during the voyage as a large amount of German U-Boat activity was reported with several ships being hit and sunk in the area only days before. The crew were given detailed orders when they started their voyage. They were instructed to sail to Milford Haven in Pembrokeshire, Wales first and wait until it became night, so the SS Ardmore could cross the Irish Channel under the shield of the darkness of night.

In accordance with instructions she called at Milford Haven, leaving shortly after. At 10pm on 13 November, when about six miles off the Coningbeg Light Vessel, on the Wexford coast, a challenge was flashed out by morse signal asking: “What ship is that, where bound?” Captain Murray, in accordance with sailing instructions ordering him to answer challenges, replied: “Ardmore, London to Cork”. The night being hazy, it was problematic to view objects at very great distance, sometimes the haze developed into a dense fog, and although the outline of the vessel suggested a patrol boat, there was agreement in the post attack and report writing phase that it was a submarine, which sent the SS Ardmore to the bottom of the sea.

At about 10.30pm, when Captain Murray and Richard Jagoe, chief officer, were on the bridge, an enormous explosion happened on the starboard side forward of the bridge, quaking the ship from stem to stern, at the same time shattering g all the glass in the wheel-house. The Captain ordered the boats to be launched immediately, and with the chief officer assisted to lower the forward starboard lifeboat, some of the crew being already in it. The ship remained upright for a very short time, then suddenly plunged head foremost into the depths of the sea, taking everything and all on board down with her.

The chief engineer Michael O’Sullivan and engine room staff were killed by the torpedo explosion. The second mate before jumping into the sea. put a coloured signal light in his pocket, and when clinging to the broken boat managed to ignite it. The flare enabled the drowning men to secure pieces of wreckage, which kept them afloat. Captain Murray and the second-engineer. who was injured, spent a terrible night, clinging to the up turned boat, with seas breaking over them.

Many of the hands were left struggling in the water. The captain and six others managed to reach one of the starboard lifeboats, and when the swirl of waters calmed down over the sunken vessel, searched about in the inky gloom for any who might be afloat. Through the night they drifted to and fro.

A poignant tragedy was that listed amongst those lost were two men both named Timothy Twomey. They were a father and son, and residents of Mill Cottages, Glanmire. The younger man could have been saved, but he went to the rescue of his father who was trapped below and even though both were strong swimmers they were lost. The younger Twomey had a baby son, Jimmy, of fifteen months. He grew up to be a well-known GAA figure in the Glanmire-Glountane area and was a prominent hurler with Sarsfields Hurling Club.

The two rescue boats, one was a patrol boat called Au Breitia and the second was an American steamship called IH Lookingback. One of the first survivors to be picked up was Corkman Michael Walsh who was the cook on the ship. He had spent some considerable time in the water, hanging on to a cattle board spar, and was suffering severely from shock. He was immediately conveyed to hospital, and at first it was thought that he was the only one saved from the ill-fated vessel. Later, however, news reached the port that seven other members of the crew had been rescued. Later another vessel came across a boat with the captain and six men, took them on board, and conveyed there to Queenstown. There were no further survivors.

Note: My public historical walking tours are finished till next Spring; thanks to everyone who came out and walked the different suburbs this year. Secret Cork, which is my 2017 book and published by Amberley Press, is now in Cork bookshops.

Captions:

921a. SS Ardmore, c.1910 (source: Cork City Library)

921b. Coningbeg Lightship off Wexford coast, early twentieth century (source: London Metropolitan Archives)