Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 6 January 2011

In the Footsteps of St. Finbarre (Part 242)

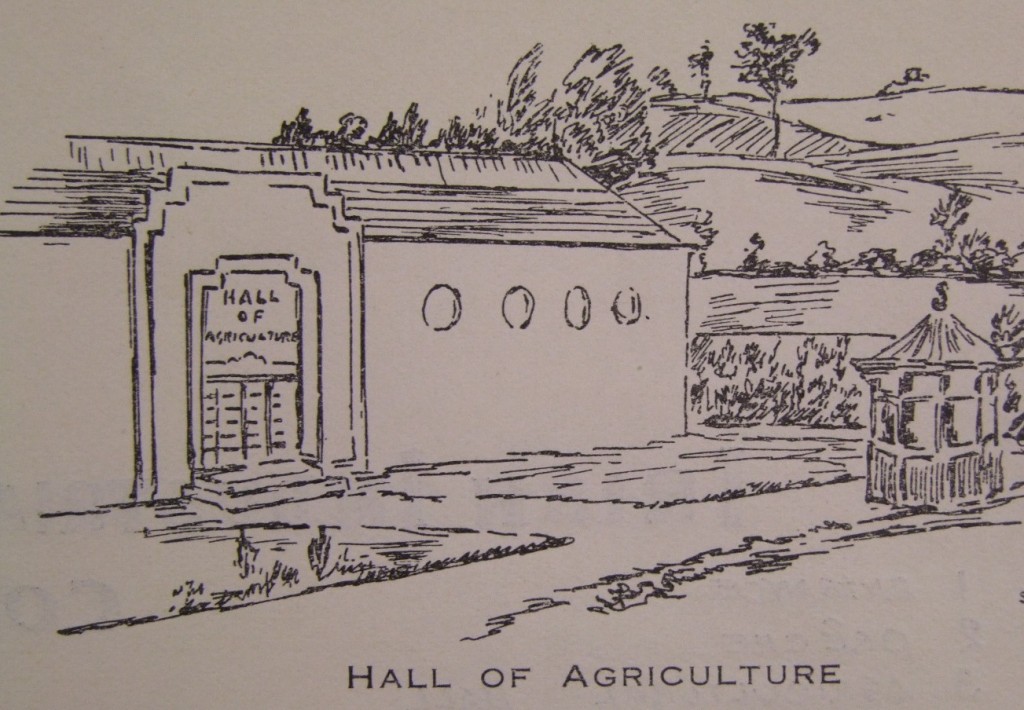

Through the Agricultural Hall

Continuing our imagined walk through the Irish Industrial and Agricultural Fair held on the Straight Road in 1932, the archived fair catalogues reveal much about what was on display but also the aims of the fair. The promotion of Ireland and its ideas, enterprises and manufactures was a priority.

One of the central buildings in the fair was the Agricultural Hall. In 1932 approximately 53% of the working population in the country was employed in the agricultural sector (c.6 % in 2010). Most Irish farmers owned their own land, some 11 million acres having been purchased as a result of the Land Acts of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. In addition Ireland had a strong dependence on Britain to export its agricultural produce.

The Agricultural Hall showcased the work of the young State’s Department of Agriculture. Their exhibit encompassed the development of several phases of Irish agriculture such as the improvement in live stock, increased production in poultry, better methods of marketing, the improvement of agricultural seeds, manures and cereals, the increase in forestry plantation areas, the nature of the agricultural education provided for children in the Irish Free State under the Department’s educational schemes as well as illustrations of some of the activities of the agricultural staffs of University Colleges Cork, Dublin and Cork.

As a context, historians such as Diarmuid Ferriter and Joe Lee, through their publications, reveal that ten years previously to 1932 one of the first acts of the new Irish Free State government was to develop Irish agriculture. Sugar beet production was begun and standards were applied to all butter and egg production. An Egg Act was passed in 1925 standardising all egg exports for testing and preservation methods. A Dairy Production Act was passed in 1924 requiring registry and packaging standards for all butter and milk products. A Bull Act was passed requiring licensing and inspection of all bulls, some 18,000 animals, for their suitability for breeding. This act applied to pigs, horses and rams as well.

The exhibit in the poultry section at the Cork fair was designed to indicate the progress that had been made in egg production. That was shown through the results obtained from the different breeds of poultry entered in the egg laying competitions in the nearby Munster Institute on the Model Farm Road from 1913 to 1931. In the marketing section of the fair, a model egg store was displayed, which showed the layout and equipment required for an egg store registered for the testing, grading and packing of eggs for export. During the period of the fair, the Department of Agriculture conducted classes in the section for the purpose of training pupils in the grading, testing and packing of eggs.

In the livestock exhibit, photographs illustrated the different breeds of live stock throughout the Irish Free State and the improvement brought about by the Department’s Live Stock Schemes. Diagrams and graphs showed the annual value of the live stock export trade and the development of the cow testing schemes. Maps and photographs also illustrated the work carried out at the Department of Agriculture’s forestry stations and the development of the various types of forest trees at these and at other centres throughout the country. Initially, the Irish Free State carried out most tree planting to stop Ireland’s deforestation and to decrease Ireland’s timber dependency. Most of the new state forests were grown on mountain land and consisted mainly of ‘exposure-tolerant’, fast-growing conifers.

Four years previous to the Cork fair, a new Forestry Act was introduced to restrict the felling of trees. This was the first time the State took measures to control the felling of trees and empower the Minister of Agriculture to force the replanting of felled areas. The Act also empowered the Minister to provide non-refundable grants to private landowners. The first planting grants were made available in 1931. By this time there were only 220,000 acres of woods in the country and any new forest planting that occurred was undertaken almost exclusively by the State. Perhaps one of the most famous afforestation projects in the Lee Valley was that of the initial 350 acres of forest planted in Gougane Barra in 1938. The plantings were largely of Lodgepole Pine, Sitka Spruce and Japanese Larch, three species that thrive in poorer soils and stand up well to exposure. The Sitka Spruce, native to a narrow coastal belt from Alaska to California is particularly resistant to constant winds and suits a wide range of soils. Lodgepole Pine, is so called because the North American Indians used its stems as poles for their wigwams while the Japanese Larch is quite distinct in its appearance as a soft feathery light-green needle tree.

Almost all of the new afforestation was undertaken by the state up until the Second World War when afforestation rates naturally fell. Once again demand for fuel and timber resulted in large-scale deforestation. The Forestry Act of 1946 introduced a comprehensive legal framework for forestry in Ireland. This was accompanied by a government policy to increase the rate of afforestation to 10,000 acres per annum, again pursued principally by the State.

To be continued…

Captions:

572a. Photograph of Fair grounds on the Straight Road, Cork 1932 (source: Archive of Iona National Airways, Dublin)

572b. Sketch of Agricultural Hall, from the Fair Catalogue 1932 (source: Cork Museum)