Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 10 February 2022

Journeys to a Free State: De Valera Comes to Cork

On Sunday 12 February 1922, the Anti-Treaty side marked the launching of a determined campaign by Éamon de Valera and his followers in Dáil Éireann. They were against the policy adopted by Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins in recommending the Treaty.

The announcement of the launch was issued on the previous Thursday, 9 February and stated; “It is evident from Mr Lloyd George’s speech in the British House of Commons that his policy is once more to trick the Irish people and deal with President Griffith and Mr Collins as he dealt with Messrs Redmond and Dillon”.

The Cork Examiner records that it was under the auspices of the Republican party that three platforms were erected in the heart of Dublin’s O’Connell Street, on Sunday afternoon, 12 February. The event was densely thronged with people. Thousands of men arrived led by their belief, some in uniform and nearly every one of them carrying arms. They marched in military formation and attracted great attention. De Valera in his speech denounced the treaty, declared that it denied the sovereignty of the Irish people, was signed under the threat of an immediate untenable war, and that it “hopelessly compromised the independence and unity of Ireland”.

Such was the success of the Dublin event in terms of large supportive crowds that De Valera continued his demonstrations at various towns and cities across the country. On Saturday evening 18 February 1922, the Republican demonstration with De Valera and his leading members reached Cork. On receiving a warm welcome at the railway station, De Valera in a short speech remarked: “You don’t want to go into the British Empire; you don’t want to disestablish the Republic, and if an election is forced upon you, we feel certain that the people of Cork will do their part in proving to the world that they still stand for the Irish Republic”.

On the following day on Sunday 19 February, a large public demonstration took place on the Grand Parade and was attended in every respect by a representative contingent of those who supported the Republican cause. Special trains from all the railway lines in the county were requisitioned. The influx was huge. Companies of volunteers marshalled and took their places along the Grand Parade, South Mall, on Washington Street and along the entrance to the place of the meeting. Two platforms were erected – one by the National Monument and one by the Berwick Fountain.

Tram and car services were entirely suspended along the various routes converging on the meeting space. Amongst the bands that took part in the demonstration were the Workingmen’s Brass and Fife and Drum Bands, the MacCurtain Memorial Fife and Drum Band, the Volunteer Piper’s band, and a number of drum and fife bands from across the country.

The Cork Examiner details that De Valera’s arrival was heralded with much enthusiasm by the public present, as he was motored up to the site of his platform. He was escorted by Cathal Brugha TD, Constance Markievicz TD, Seán MacSwiney TD, and other prominent supporters. At platform number one at the National Monument, the proceedings there were presided upon by the Lord Mayor, Councillor Donal Óg O’Callaghan TD. He briefly addressed the meeting in Irish and then called on De Valera to speak. De Valera stepped up with cheers, and cries of “Up the Republic”.

De Valera opened his speech by noting that he went to America to speak to the people of America, and to ask them to recognise the Republic that was “set up in Ireland by the free will of the Irish people”. Little did he dream, he described, that the day would ever come when he would have to come to the Irish people themselves, asking them to affirm that Republic that itself had set up. He noted: “What I have to say to you can best be summarised by the resolutions that I am going to propose to you. They are the same resolutions that were adopted in Dublin by tens of thousands of the citizens of the Irish capital and here in Cork today I am certain that they will be adopted equally without question by the people of the southern capital, the people of Cork”.

De Valera then read the resolutions, which repudiated the Articles of Agreement or Treaty, asserted that any election based on the Treaty would cause partition, deemed the Treaty a threat to the disestablishment of the Republic and its cause, and would do nothing to honour the sacrifices of the men and women who suffered most during the Irish War of Independence.

Proceeding, De Valera said it was not necessary for him to use any argument to impress upon them their approval of the resolutions. He appealed to the crowds present that the nation was in danger – to a greater danger than it was in 750 years. He asserted: “This was the first time in 750 years in which they had been fighting Britain that there was a suggestion to give a democratic title to England in Ireland. Up to this present every Irishman could say that Britain had No title in Ireland”.

De Valera said that it was because they were threatened by an outside enemy and an outside force thought there was any question of departing from the Republic. He noted “if the treaty was signed under duress, then the men who went over broke their faith with the Irish people”.

That afternoon of 12 February 1922, Cathal Brugha TD, Liam Mellows TD, David Kent TD, and Professor William Stockley TD also spoke of the vision of the Irish Republic under threat.

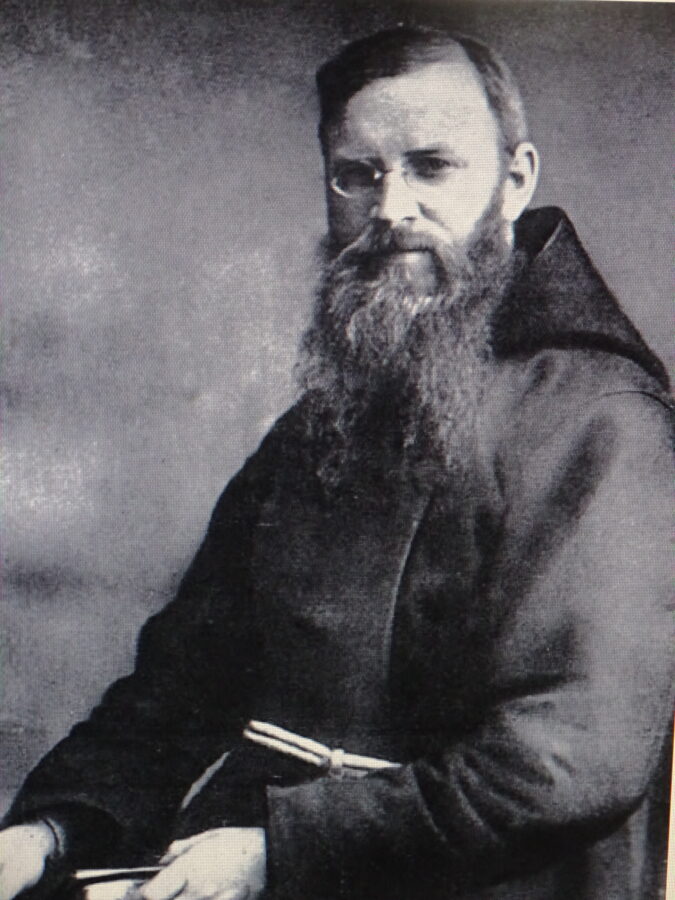

Caption:

1137a. Footage still of Éamon de Valera delivering his oration at the Anti-Treaty event in Dublin, 12 February 1921 (picture: Irish Film Archive).