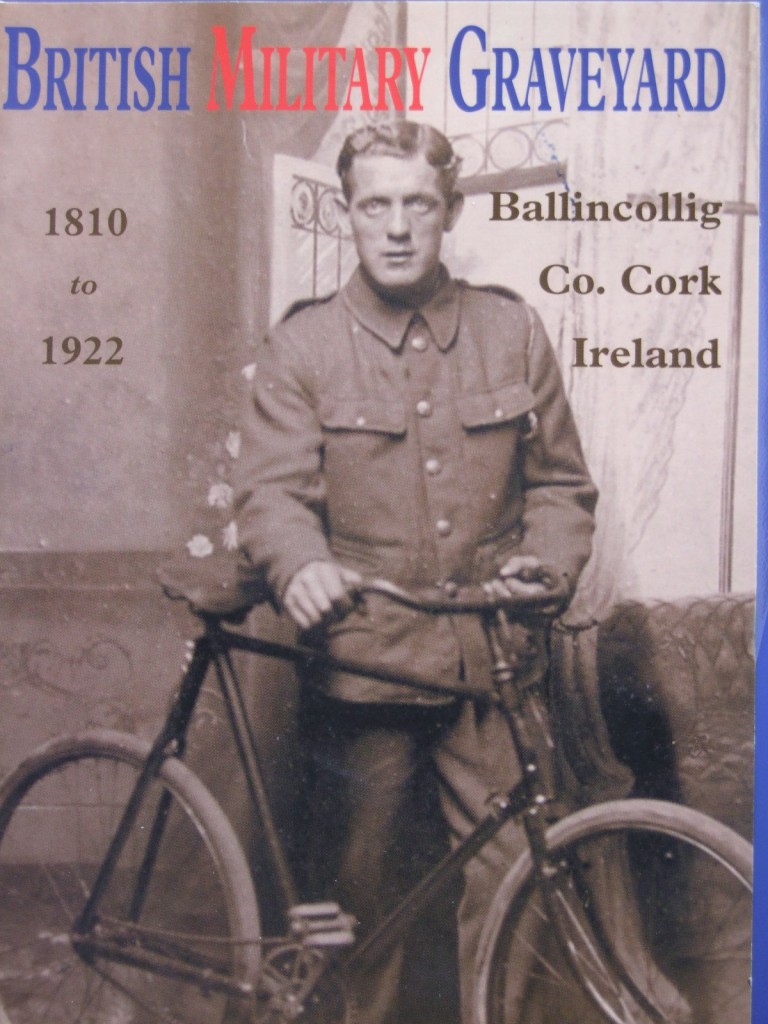

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town article, Cork Independent,

1 April 2010

In the Footsteps of St. Finbarre (Part 206)

A Soldier’s Grave

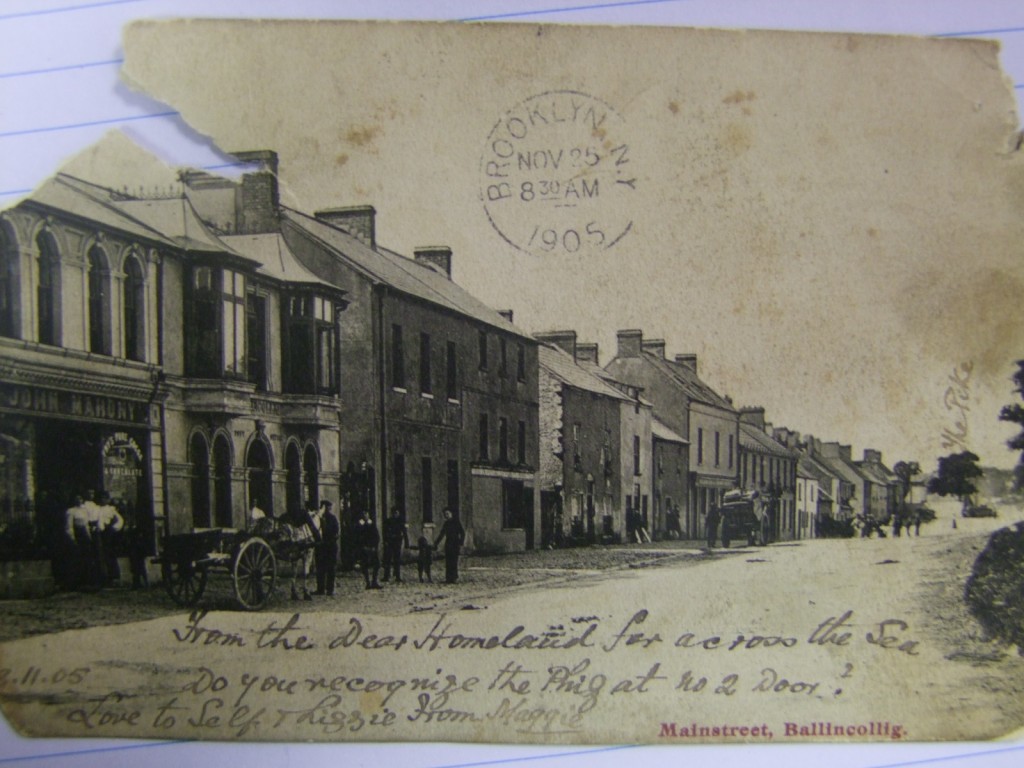

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, Emma Ryan, Main Street, Ballincollig, married William John Regan who was stationed in the local barracks. William was a bandmaster with the 3rd Dragoon Guards. They had twin girls in Acra, India in 1886. William died in India whilst on active service. Subsequently Emma returned to Main Street Ballincollig to continue her life. She arranged a child minder and studied maternity nursing. Eventually she became the local midwife/ nurse in Ballincollig.

The above is just one real life that has been unearthed by Anne Donaldson through her work and publication on the military cemetery, which was attached to Ballincollig Barracks. Apart from the biographies of member of the British army in Ireland up for scrutiny, Anne’s book I feel brings the reader onto other grounds of research. In recent years, the commemoration of Irish soldiers has shifted to studies of their contribution in the British army. As Ireland’s popular history focuses on the colonial impacts, recent studies have highlighted that 210,000 Irish soldiers took part in the first World War alone, of whom at least 35,000 were killed. Many of the Irish soldiers who died in that War lie in the fields of France, Belgium, Germany, Greece, Turkey, India, Iran, Iraq, Italy, Egypt and South Africa.

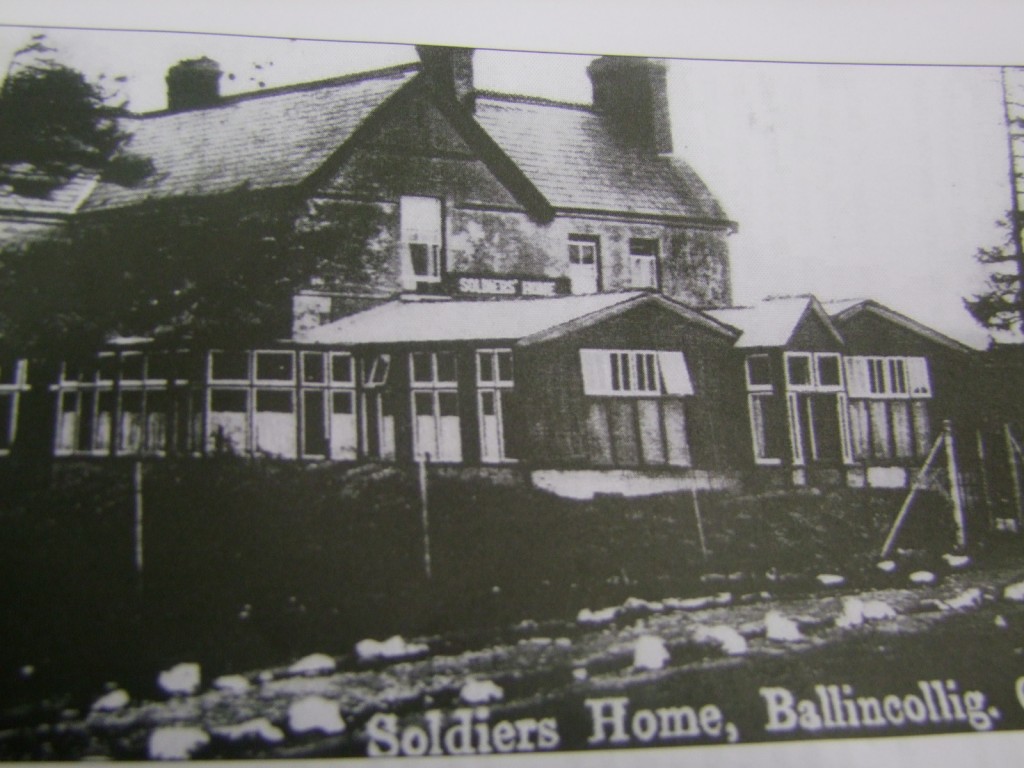

However, active service was also seen in Ireland. The role of the British citizen in the British army in Ireland had huge socio-cultural implications for every settlement that they were close to. Like those who died and who were buried overseas, their story too is largely forgotten. In their time, they also played an important part in Irish social history. A garrison such as the one at Ballincollig would have brought wealth, employment and opportunity. The lives of the garrison and the town would have become intertwined and in many ways mutually dependant.

As with the barracks, the military cemetery was also integrated into the Ballincollig landscape. The cemetery through its head stones provided an honour in death in the service of the British nation, the idea of a human sacrifice for the cause. The cemetery is a type of hero’s grove. The first map showing the site appears to be the 1834 ordnance map. The earliest inscribed gravestone found to date is the barrel grave of Isabella Wall dated 15 November, 1813. The earliest burial record found is of Mary Duggan, daughter of Gunner William Duggan and his wife May of the 9th Battalion, Royal Artillery buried a month earlier on 13 October, 1813. The final burial seems to be that of Private E.C.J. Stratton of the 17th Lancers, who was buried on 13 June 1920.

Initial survey work of cemetery was completed by Leslie Rice and Richard Henchion in 1995 and they noted 77 gravestones. Anne Donaldson added to this by consulting the army burial registers stored by the Church of Ireland at Carrigrohane. Anne identified 352 individuals as been buried in the Ballincollig Military Cemetery. A total of 291 soldiers are either buried at there or have a close family member buried there. Forty-seven officers including surgeons, a schoolmaster and bandmasters are similarly associated with the graveyard. Known adult males number 157. Of these 3 are known as married men. Known adult females amount to 34. Ages are known for two hundred entries. Ages at death range from eight hours to 77 years. Only six cases of death in Cork hospitals could be ascertained.

In my recent chat with Anne, she highlighted the stories of several individuals buried in the cemetery. However, her early work is also expanding as more and more genealogical websites and census documents in the UK and Ireland are put online (e.g. www.ancestor.co.uk). Her findings reveal the significant depth of complexity of the lives of soldiers within the Barracks. The stories indicate that there were many aspects to a soldier’s life in Ireland in the years between 1810 and 1922. Trauma, fear, loneliness became the lot of many soldiers who were stationed far from home. So Anne’s work apart from recording, the process itself has also led to a partial restoration of the memory of forgotten souls. Three examples are given below (more can be read in Anne’s book).

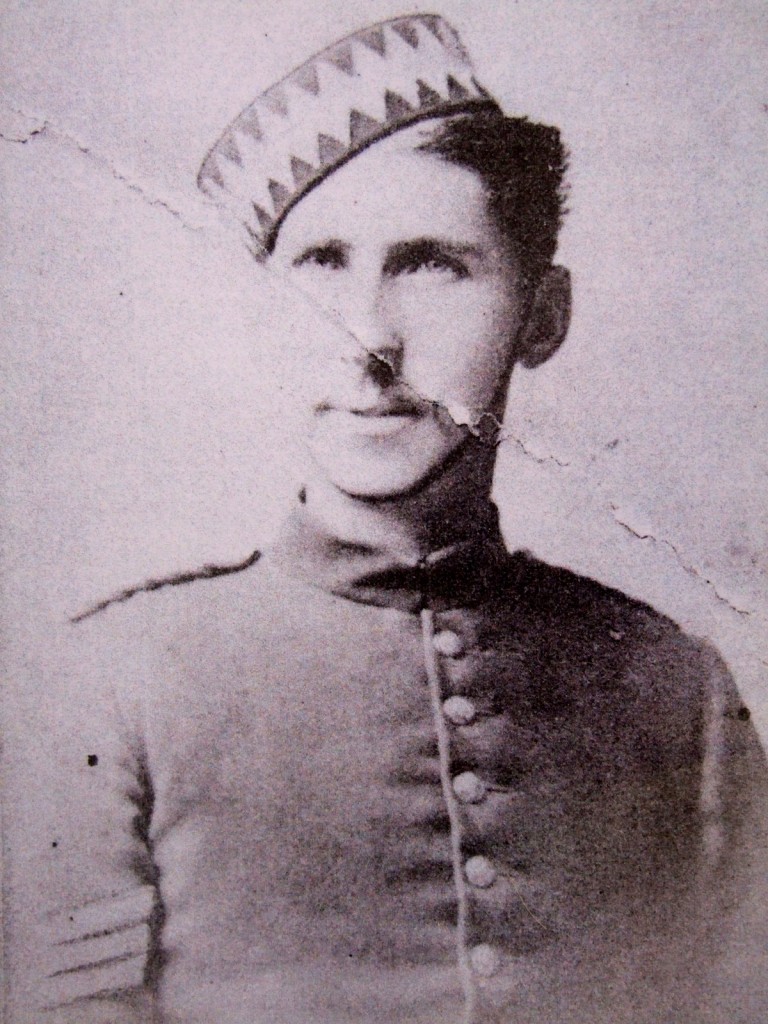

Shadrack Gould, born 1 January 1855, was from Bradfield, Essex, England. He was a soldier in the 2nd dragoons (Royal Scots Grays) from June 1873 – until his untimely death in 1882/ 1883. According to family tradition, whilst stationed at Ballincollig, Shadrock Gould died from an accidental gunshot wound delivered by his commanding officer.

A Bengamin Blackwell was born in 1844 in Wrexham Wales. In his younger years he was on board the ‘Formidable’, a ship for destitute and homeless people based at Bristol. A total of 480 boys were on that ship. He died on 16 July 1890. Twenty-two years old Bombardier Charles Mason was, in 1847, remembered by the non-commissioned officers and men of no.1 Company, 4th Battalion. His epitaph reads: “Comrades see a Soldiers Grave, Tread lightly O’er this sod. And Now that you. Your soul save, My soul seek Your earthly Peace with God.”

The graveyard became the responsibility of the Office of Public Works in 1922 and its heritage remains to be integrated into the way of life of modern Ballincollig.

To be continued…

Captions:

533a. Andrew Gillespie, died at Ballincollig Barracks on 26 August 1915 (pictures: Anne Donaldson collection)

533b. Shadrack Gould, died at Ballincollig Barracks in 1882/ 1883

Inheritance, Heritage and Memory in the Lee Valley

Inheritance, Heritage and Memory in the Lee Valley