Category Archives: Cork History

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 18 October 2018

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 18 October 2018

The Recruitment Dilemma

Sunday 20 October 1918 brought the supporters of Cork Sinn Féin and the World War I Recruitment Office clashing again at a recruitment meeting of the Grand Parade. The Cork Examiner recorded an angry crowd of some thousands present, who interrupted and prevented the speakers from their orations. Previous to the meeting military bands promenaded the principal streets. aeroplanes flew over the city and dropped literature in connection with condemnation of the sinking of the RMS Leinster. The vessel operated by the City of Dublin Steam Packet Company, served as the Kingstown-Holyhead mailboat until she was torpedoed and sunk by German submarine UB-123 on 10 October 1918.

Mr Maher Loughnan, BL who was given a quiet hearing, said he presided in the absence of Mr Harold Barry, the County High Sheriff. He considered it not only a pleasure but a duty to address them, for he was there for no imperial motive whatsoever.

Captain Irvine, on coming forward, was greeted with groans and hisses. For some time this continued from a section of some hundreds right in the centre of the crowd. After a while there was a lull, and Captain Irvine began by saying; “I have great pleasure in addressing you today, but before I speak to the subject proper I want to tell you of my little experience in the South. I came from the North, and there the South has a reputation of breaking up meetings. I don’t believe any Irishmen will prevent a speaker”. The men in the crowd then began to sing the Soldiers’ Song. The chairman appealed for order and asked them to give the gentleman a chance. The singing continued, and voices shouted; “You will get no recruits here”, and “You are like a statue-up there, we will give you no chance”, and counter shouts of “Up the khaki”, to which voices answered: “Up the rebels every time”.

Captain Irvine was unable to proceed and resumed his seat. A funeral passed; Captain Irvine, directed attention to the fact. His voice did not carry beyond the immediate area of the waggonette, and it was not until he stood to attention that the crowd became aware of the passing cortege.

Captain Irvine began again: “Men of Cork. I am here today to ask you to avenge the Leinster”. The hissing and booing broke out afresh, and Captain Irvine asked, “Do you cheer those men who sank the Leinster? Do you cheer the men who committed every outrage imaginable in this war?”. The singing now was taken up, and there was much hissing and jeering, and some counter-cheering. To this, Captain Irvine said: “Men must be absolutely misguided who cannot listen to sound argument – men who cheer an abominable outrage like the sinking of the Leinster. I am perfectly certain there are thousands of men in this assemblage who hate and detest every outrage that the Germans committed, and I think it a great pity that a few men in the crowd should try to stop a man telling that which he believes to be true, and give honest reasons why men should at the present moment, instead of cheering the Germans should help the Allied cause”.

The singing all the time continued, and some replies made by people in the crowd were not heard. Captain Irvine orated; “It is not sportsmanlike, or playing fair with the fair name of Ireland, which had a reputation for sportsmanship, and I believe at least the vast majority of Irishmen are sportsmen, and it seemed a great pity that a few should try to sally her fair name. If you wish to be represented at the Peace Conference as a nation, how can you expect it if you are not going to give the Allied cause, the winning cause, the fair play it deserves?”.

The rival parties ended up shouting at each other, and neither had the slightest chance of hearing a Lieutenant O’Riordan who was introduced. Freedom, nationality, and liberty was the cause he espoused, and he believed that to that sacred cause the young men of Cork were prepared to listen. He shouted above the din, “As an Irishman I ask the men of Cork to follow in the footsteps or those glorious sons of Cork, the Munster Fusiliers. That local regiment shed undying lustre on Cork, and their memory would live as Irishmen who had fought for the glory of their country”. Throughout his speech the noise was incessant, and the meeting looked angry J B Connolly, a prisoner of war in Germany, faced the meeting and also attempted to address it but with no better success.

As the speakers proceeded to leave, there was a surge towards them. They walked towards the City Hall, followed by a few hundred persons shouting and booing. They were pressing in on the speakers, and the police drew their batons. There was a general stampede, and in the rush some persons got baton strokes, while others dodged and narrowly escaped being trampled-on. The baton charge, which lasted for a few minutes, was indiscriminate, but as far as could be ascertained no one was injured. After some time the place cleared, and no further incidents took place.

Captions:

968a. Irish Soldiers of the 16th Division during World War I (source: Cork City Library)

968b. Irish Soldiers in the trenches on the western front of World War I (source: Cork City Library)

Kieran’s new book, Cork in Fifty Buildings (2018, Amberley Publishing) is now available in Cork bookshops.

Kieran is also showcasing some of the older column series on the River Lee on his heritage facebook page at the moment, Cork Our City, Our Town.

Kieran’s Historical Talk & Walking Tours, 18-21 October 2018

Thursday, 18 October 2018, Cork: A Hundred Years Ago, a sit down talk with Kieran exploring pictures and postcards, in association with Cork Age Friendly City, Firkin Crane, Shandon, 11am (free, duration, 90 minutes)

Saturday 20 October 2018, Our Lady’s Hospital, historical walking tour with Kieran; learn about the former Victorian asylum; meet at the gates of Our Lady’s Hospital, Lee Road, 11am (free, duration: two hours)

Sunday 21 October 2018, The Marina and Blackrock, historical walking tour with Kieran, learn about the development of the Marina walk, meet at grotto on Blackrock Pier, 12.30pm (free, one hour, as part of the Marina Play Sunday and Urban October)

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 11 October 2018

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 11 October 2018

Stories from 1918: The Spanish Flu Arrives

The Spanish Influenza pandemic or Spanish flu was one of the devastating pandemics in human history. It resulted in an estimated 25 million death worldwide. It is said to have originated at a US army camp in Kansas in early March 1918 and spread to the front line of World War I with the infected soldiers. The first wave and strain of influenza was mild. However, the second wave came as the flu, and then transformed into pneumonia, which led to death. On being brought into Ireland it killed about 23,000 people in 1918. In particular, the deaths in Dublin were high – 250 deaths a week were recorded by November 1918. Local authorities across the country tried to secure more beds in hospitals and to recruit more doctors, many of whom were infected by the influenza.

Up to October 1918 Cork had been almost immune from the serious influenza epidemic that has levied such a toll in other Irish cities. Reports in the Cork Examiner on 23 October 1918 detailed that influenza had only appeared in Cork in a few isolated cases. The Medical Officer of Health at a meeting of the Public Health Committee, said a few cases had come under his observation. It had broken out in some rural districts. In the Carrigaline district no letters were being delivered owing to the local postman being confined to his sickbed.

The Lord Mayor of Cork, Thomas Butterfield, through the medium of the local press, advised people not to congregate together, and entertainments of all kinds were to be avoided. Those infected with the influenza were advised not to mix with others. The introduction of the epidemic into the schools and public institutions was to be prevented. Public meetings could not be held. The Medical Office of Cork Corporation remarked that the age of an infected person was an important factor. The mortality amongst the elder people was much higher than amongst the adults, and children took the disease in a mild form.

By the 29 October 1918 a very many fresh cases of influenza were reported in Cork and one death at least had been recorded. In the way of taking preventative measures some of the city schools had already closed down, and school inspectors noted a marked falling off in attendance. On visiting the homes of absent pupils, it was found by these inspectors that numbers of children were confined to bed.

As a precautionary measure University College, Cork, closed and remained completely closed for a fortnight. A Retreat, to be opened at the Honan Chapel for female students was postponed. Farranferris College closed at short notice as did the Carnegie Library (under the watchful eye of City Librarian James Wilkinson).

Up to the third week of October 1918, dispensary doctors in Cork City did not have to deal with very many cases at their dispensaries, not more than 35. In the poorer and vulnerable parts of the city the disease had not gained any major grip. One medical practitioner, commenting on this fact regarded it as unusual in the face of past experiences. He was of the opinion, however, that previous sufferers from the influenza were not immune from further attacks. The strain of influenza was very contagious. One media report highlighted that of a family of six, they were all stricken within a few short hours from the time that the first symptom appeared in one of their children.

The number of interments at the principal Cork burial grounds was about double the number daily interred in normal time. The number of requests made to Cork City hospitals from many parts of Ireland and Great Britain for nurses to cope with the epidemic in other centres was altogether in excess of the number that could be relieved for such duties.

A letter published in the Cork Examiner on 29 October 1918 revealed the heartfelt plea of a citizen to take the spread of the influenza epidemic seriously:

“Dear Sir, The death toll from the influenza epidemic throughout the country is rising steadily, and in Dublin alone the number of burials in Glasnevin Cemetery during the past week was 120 higher than the average normal weekly number- Cork, so far, seems to be escaping lightly, but we must not shut our eyes to the fact that the number of cases is increasing daily. I have medical authority for stating that prevention is better than cure, and reluctance to take steps to prevent the spread of the disease is criminal. Schools, of all kinds and places of entertainment. should be closed at once, without a day’s delay. If this is not done the disease will spread, and we shall be faced with a serious situation. The life of the most humble citizen is dear to me and as a father of a large family, I claim the right to demand that everything essential be done now. The students of the University College, Dublin, are undergoing preventive treatment by inoculation, and I would strongly suggest that our local medical gentlemen obtain supplies of the influenza vaccine, so that any citizen who wishes may be inoculated. Of course, those in a position to pay a reasonable fee for this should be prepared to do so. The laboratories of our University College could be utilised for the preparation of the culture-Faithfully yours, CITIZEN”.

Kieran’s new book, Cork in Fifty Buildings (2018, Amberley Publishing) is now available in Cork bookshops.

Captions:

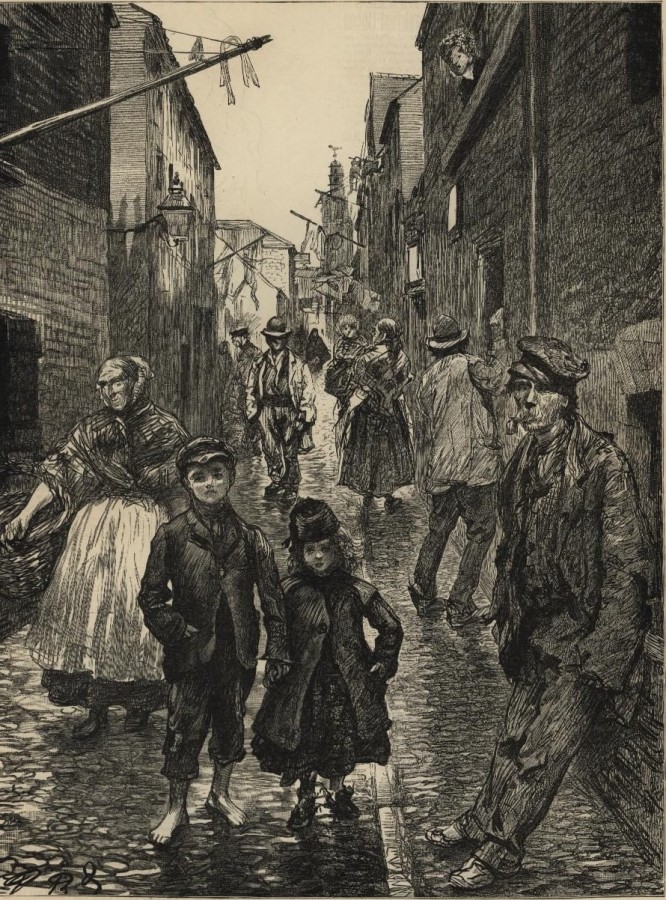

967a. Harpur’s Lane c.1900 (now Half Moon Street) from Harpur’s Weekly newspaper (source: National Library, Dublin)

967b. Picture of new James Wilkinson mural on Anglesea Street; He was the first City Librarian of Cork Carnegie on Anglesea Street from 1905-1920; the work was funded by Cllr Kieran McCarthy and designed and painted by Kevin O’Brien and Alan Hurley (picture: Kieran McCarthy)

Talks and Walks with Kieran, October 2018, (all free, average duration: 2 hours)

Saturday, 13 October, The Friar’s Walk, meet at Red Abbey tower, Mary Street, off Douglas Street, 11am

Sunday 14 October, The Lough & its Curiosities; meet at green area at northern end of The Lough, entrance of Lough Road to The Lough; 2pm (note time change)

Thursday, 18 October, Cork: A Hundred Years Ago, A sit down talk exploring old pictures and postcards, in association with Cork Age Friendly City, Firkin Crane, Shandon, 11am

Saturday 20 October, Our Lady’s Hospital; meet at the gates of Atkins Hall, former Our Lady’s Hospital, Lee Road, 11am

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 4 October 2018

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 4 October 2018

The Problem of a Milk Supply

One hundred years ago this week, the provision of milk to citizens became a contentious issue. Milk was an important commodity for citizens especially with a rationing system in place arising from the ongoing war. Annually Cork City needed circa 500,000 gallons of milk. Over 20 creameries in county Cork supplied the city and region’s needs.

The Cork Dairy Farmers’ Association were an effective lobby group, which was established in September 1913 with a determined effort to organise themselves and push for the best prices for their member’s milk. They met on Saturday 5 October 1918 to consider the action of the Local Cork Food Control Committee earlier in that week who fixed the milk price at a lower level than expected for the month of October. The proceedings were private, but an official report was supplied later to the Cork Examiner. The meeting was held at the Marlboro Street Hall with Mr Joseph Forrest, chairman presiding.

It was unanimously decided that the price fixed by the Local Food Control Committee was entirely inadequate, and that members all decided to lessen their system of farming output straight away. It was highlighted that beef and butter production would pay better than milk. Several farmers declared they would get out of the dairy cow industry. It was decided to cease supply to the city on the subsequent Wednesday. Exceptions, however, were to be made in the case of hospitals, asylums, workhouse, and prisons. Worry hit in across the city for fear of no milk.

The Food Control Committee for Ireland in their published order prescribed the maximum price applicable, on the occasion of a sale, other than a retail sale, of milk produced in any part of Ireland. They oversaw prices of milk produced within the limits of the Dublin Metropolitan Police Area, and within the boundaries of the County Boroughs of Belfast, Cork, Londonderrv and Waterford. Prices were set at the rate of 1s 3d per gallon from the 7 to 31 October 1918. During the months of November and December, the rate of 1s 10d per gallon was set and for January, February and March 1919 the rate of 2s per gallon was established.

Mr John Horgan, Chairman of the Local Food Control Sub-Committee, went to Dublin to present the views of the Cork Dairy Farmers’ Association and their threat to cut off the supply from the city. Elsewhere there were other comments made from members of the Cork association who presented a different view that the decision of the body was not unanimous, and that the threat to supply no milk to the people was only supported by a very small proportion of the members. It was also learned that large numbers of vendors and housekeepers in all parts of the city had received promises from their suppliers that there would be no discontinuance in their supplies.

The situation was also discussed at a special general meeting of the Cork Milk Vendors’ Federation at Stephen’s Hotel. Mr T O’Donovan (chairman) presided, and there was a large attendance. The Chairman expressed regret at the ongoing dispute, and sincerely trusted that the farmers and Food Control Committee would arrive at an amicable settlement. Their members as distributors deemed themselves in an extremely awkward position, because if no settlement was reached they would had no option but to refuse to supply milk unless it were delivered to them at the controlled price. They were fully aware to the serious consequences that would be incurred owing to a shortage of milk, especially in the case of children.

By the 12 October the disagreement between the Cork Dairy Farmers’ Association and the local Food Control Committee, had been settled. Mr Patrick Crowley, of the Cork Industrial Development Association, and Mr Richard Wallace, of the Poor Law Board, were active in an effort to discover some solutions. They invoked the assistance of Capuchin priest Fr Thomas Dowling (see previous columns) and arranged a meeting between him and the Cork Association.

Father Thomas made a strong appeal to the farmers, to alter their position and to continue the milk supply to the city for the sake of the sick, the children, and the poor. He pointed out that he was there not to discuss whether the farmers could or could not supply milk at the prices fixed for them by the local Food Committee. He promised the Association that if they would listen to his appeal he would exercise every influence to see that their case had full and fair consideration.

A considerable discussion followed, in which the members of the Cork Dairy Farmers’ Association dwelt upon their grievances. Finally, the meeting agreed to accede to the request. In announcing it, the members of the Association detailed they were not yielding to any public uproar but would give in to the appeal of Fr Thomas. Following the conference with Fr Thomas, the news was sent by messengers. and telegrams to the various districts authorising a renewal of the supplies immediately, so that a return to a normal condition of supply would be immediately implemented.

Kieran’s new book, Cork in Fifty Buildings (2018, Amberley Publishing) is now available in Cork bookshops.

Captions:

966a. Meadowvale Creamery, Charleville, c.1900 (source: National Library of Ireland, Dublin)

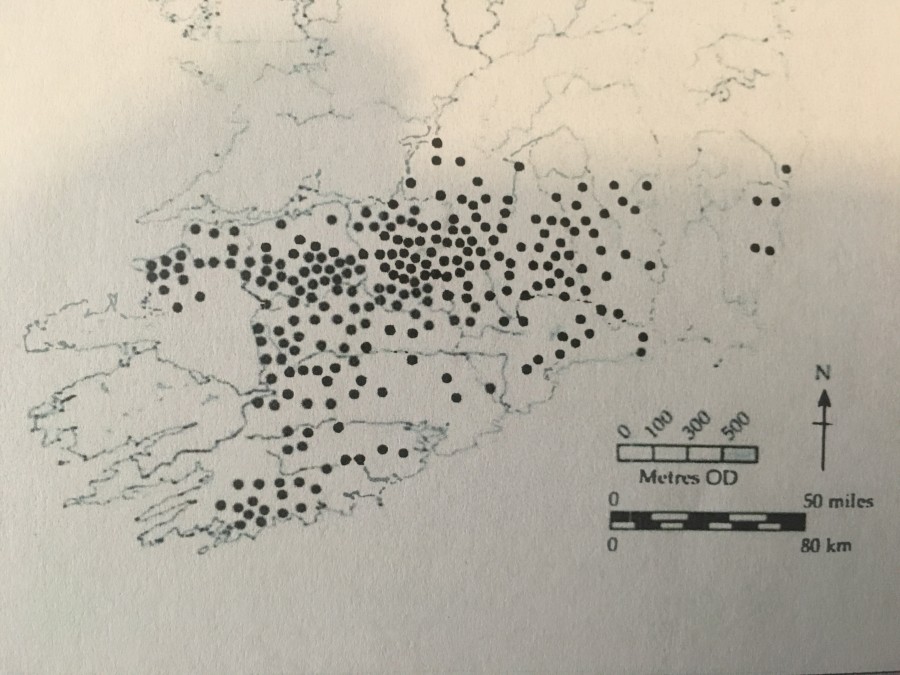

966b. Map of creameries in south west Ireland, 1910, adapted from F H A Aaalen, K Whelan, M Stout, 1997, Atlas of the Irish Rural Landscape, Cork University Press (source: Cork City Library)

Talks and Walks with Kieran, October 2018, (all free, average duration: 2 hours)

Saturday 6 October, Douglas and its history, meet in the carpark of Douglas Community Centre, 11am

Saturday, 13 October, The Friar’s Walk, meet at Red Abbey tower, Mary Street, off Douglas Street, 11am

Sunday 14 October, The Lough & its Curiosities; meet at green area at northern end of The Lough, entrance of Lough Road to The Lough; 2pm (note time change)

Thursday, 18 October, Cork: A Hundred Years Ago, A sit down talk exploring old pictures and postcards, in association with Cork Age Friendly City, Firkin Crane, Shandon, 11am

Saturday 20 October, Our Lady’s Hospital; meet at the gates of Atkins Hall, former Our Lady’s Hospital, Lee Road, 11am

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 27 September 2018

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 27 September 2018

Stories from 1918: Analysis of a Port Trade, September 1918

The Irish Sub-Committee of the Parliamentary Committee on Inland Transport sat in Cork City Hall on Saturday morning, 14 September 1918 to examine evidence on economic interests in southern Ireland. The sub committee was sent to investigate and report upon the facilities for transport offered by the port and canals of Ireland, and to make suggestions for their development. The members of the committee comprised high ranking politicians with commercial background, which included Sir Arthur Shirley Benn, M.P., Chairman Colonel John Gretton M.P., Mr William Field M.P, Mr W. A. Lindsay M.P., Mr M. Keating M.P., Mr Walter Hudson M.P. and Mr P. J. Hannon.

The Lord Mayor Councillor Thomas Butterfield welcomed the members of the committee, especially the chairman Sir Arthur Benn (1858-1937). Sir Benn was a Corkman from Eglantine House on Douglas Road. Arthur was the Eldest son of the Rev. John Watkins Benn, rector of Carrigaline, and Douglas, County Cork. Arthur had a prominent career in commerce and politics. For many years he lived in the United States and Canada, and was Vice-Consul at Mobile, Alabama, from 1898 to 1902. Arthur became a member of the London County Council in 1907. During the First World War he acted as honorary treasurer of the National Committee for Relief in Belgium and was made a Commander of the Order of the Crown of Belgium in recognition of his services.

The core statement at the Cork meeting was taken from Mr James Fawsett who was representing the Council of the Cork Industrial Development Association. He summarised the monthly bulletin of the Association for February 1918 which set out the challenges and known data concerning the future of shipping in the region but in particular (1) the situation of Cork Harbour, (2) the harbour’s facilities for shipping, (3) the character of the trade and commerce that passed through the harbour and (4) the advantages which it offered for the successful conduct of international trade, especially after the war.

James Fawsett outlined that for very many years before the war Cork was the North Atlantic mail port, and as such served the commerce of Western Europe and North America. In pre-war days the port accounted, for two-thirds of the foreign shipping using Irish ports. It was popular with ship-owners. It was served by railways with sidings along the deep-water quays both at Queenstown (now Cobh) and Cork. The railway lines connected with other trunk lines of the country. The harbour’s spaciousness and security for shipping made it stand prominent among western European ports. Some of the largest ships afloat, at the outbreak of the war availed regularly of its safe anchorages, entering and leaving at low water spring tides. In addition to the Admiralty Dockyards at Haulbowline, the ship-repairing yards at Passage and Rushbrooke operated by Messrs Furness Withy and Co., Ltd, a firm eminent in international shipping, were doing well. Reconstruction of ships and their equipment especially of vessels up to 620 feet in length and of 80 feet in width, were completed with efficiency.

Thinking towards the future, with vision and the continual development of proper facilities, James Fawsett saw Cork as being the leading largest ship port region in Western Europe. Within the city’s docks, he deemed that the contemporary equipment of the port for handling cargo and the transport of goods was inadequate. For the quick, cheap, and efficient loading and discharging of vessels, the port and harbour required the aid of modern powerful machinery, fixed but flexible. Larger and more powerful cranes were necessary on the quays for the handling of heavy and bulky cargoes and to encourage shipbuilding. The expansion of the trade of the city called for additional wharfage and storage accommodation, in particular extending from the new Ford factory complex eastwards to the Marina.

James Fawsett laid stress on the financial losses sustained by traders owing to the congestion of goods for Cork in certain English ports, notably those of Liverpool and Fishguard. Foreign goods, for example from America, intended for Cork producers and distributors, passed by the port of Cork and were taken on to Liverpool. There the ships discharged, and the goods were transhipped to Cork.

Mr Fawsett also dealt with the fishing industry and its challenges in the coastal region. The great bulk of the fish consumed in the country came to Cork from British fishing ports. He highlighted that Cork Harbour was admirably situated to be the home base for a large fleet of trawlers, equipped with all modern appliances. Facilities for the handling, curing and packing of the fish on a large scale should be provided at Queenstown, from which it could be distributed quickly to the different markets. The fisheries at Youghal, Ballycotton, and Kinsale were in a decaying condition, due mainly to antiquated boats and gear, and to the lack of proper transit facilities for the fish at the landing places in such centres.

To James Fawcett, Berehaven in West Cork was capable of very considerable development, and, provided it be linked up with the main trunk line of railway, for example to Mallow Junction, it could play an important part in the commercial future of the country.

Kieran’s new book, Cork in Fifty Buildings (2018, Amberley Publishing) is now available in Cork bookshops

Captions:

965a. Bere Island Ferry from Castletownbere, c.1900 from West Cork Through Time by Kieran McCarthy and Dan Breen (source: Cork Public Museum).

965b. Postcard of Passage West and Glenbrook, c.1900 from Cork Harbour Through Time by Kieran McCarthy and Dan Breen (source: Cork Public Museum)

Cllr Kieran McCarthy on Facebook, September 2018

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 20 September 2018

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 20 September 2018

Irish Heart, Coventry Home

Irish Heart, Coventry Home is an exhibition, which is currently being exhibited in the new building foyer of Cork City Hall for the next three weeks. It is a project I have been involved with the last year in a small way offering heritage management support and advice on behalf of Cork City Council. The exhibition is curated by Ciaran Davis at the Coventry Irish Society. It is about Irish people who made Coventry their home between 1940 and 1970. It is based on the experiences of Irish people who have lived and worked in the city.

Many Irish people emigrated to Coventry from Cork and they have contributed richly to the culture, economy and character of the city. These links were celebrated in 1958, when Cork and Coventry were twinned with each other. The exhibition has travelled to Cork to celebrate the enduring relationship that exists between the two cities. During the Second World War, many Irish men and women came to work in Coventry’s factories and hospitals. After the war, Irish migrants were among those who came to help with the city’s reconstruction following the devastation caused by air raids. Their labour was vital, not just in construction and industry but in education, civic life and the newly established National Health Service. By 1961 there were 19,416 Irish-born people in Coventry and they formed 6% of the city’s population, which made them the largest ethnic minority in the city.

The majority of Irish people who migrated to Coventry after the Second World War were usually young people who came from Roman Catholic, working class, rural backgrounds and the majority were women. They often stayed with family members already in Coventry who paid for their ticket and helped them find employment. Men usually arrived alone and found work by applying to adverts in newspapers or through speaking to fellow Irish people. Irish people were employed in a variety of jobs, working on the buses and in hospitals, factories and schools. They were involved in the building of the ring road, housing estates and the new cathedral, supporting the city’s post-war recovery and contributing to its economy. The money that Irish migrants sent home was relied on by families who remained in Ireland. Between 1939 and 1969 the Irish economy received almost £3 billion in remittances from Irish workers.

As people settled in the city, they opened social clubs and pubs, which became vital community spaces. Irish people arriving in Coventry often headed straight to the clubs where they learnt where to find work or accommodation. A few venues even had their own lodgings. Some landlords promoted Irish welfare and held charity nights or lent money to people who were struggling. Many of the clubs were established in the 1950s, which coincided with the rise of the Irish showbands, who were renowned for their high-energy performances. In the 1960s, singers such as Joe Dolan and Brendan Bowyer toured Coventry and were popular with the Coventry-Irish community. By 1967, the Banba Club had a membership of over 1000 and on a Saturday night, an average of 650 people would come through the club’s doors. There were also people in the community who vowed never to drink alcohol. In 1964 some of them set up the Coventry branch of the Pioneer Association, an organisation originally set up in Ireland. They held dances, sporting events and dinners at the Pioneer Hall in Coventry. Few of the Irish clubs remain in the city, but their legacy endures because many Irish people met their future spouses at the dances

A number of Irish sports clubs were established in Coventry, offering sports such as hurling, Gaelic football and camogie – a sport similar to hurling played by women. Priests and other members of the community helped to set up these teams because they were concerned that young people were forgetting their Irish roots. There was sometimes competition between the clubs to recruit the best Irish sportspeople in Coventry. Gradually, the teams expanded and some purchased clubhouses where they could socialise after matches. Players often brought their families to watch the games and their children sometimes went on to represent the same team. The clubs held exhibition games featuring Irish teams. In 1966 St Finbarr’s Sports and Social Club held a hurling match between Galway and Meath, which was watched by around 10,000 spectators. The clubs initially ran male-only teams, but in 1971 a group of women established their own camogie team in Coventry.

Most Irish people who came to Coventry belonged to the Roman Catholic faith. A smaller number of Protestants also migrated, and for both groups religion played an integral role in their lives. Irish Protestants often joined pre-existing parishes, but the higher number of Irish Catholics meant that new churches needed to be built. In 1913 there were two Catholic churches in Coventry. By 1983 this had grown to 17, many supported by donations from the community. In the 1950s and 1960s a number of Catholic schools were also built to accommodate the expanding Irish Catholic population. For many Irish migrants it was important that church attendance was continued by the next generation. Couples got married in local churches and their children received their first sacraments in the same parishes.

To learn more (and to contribute to the project) Irish Heart, Coventry Home is currently on display in the foyer of the new building in Cork City Hall. The curator Ciaran Davis from Coventry Irish Society will be present at the space for Cork Culture Night, Friday 21 September.

Captions:

964a. Irish Heart, Coventry Home exhibition at Herbert Gallery, Coventry in March 2018 (picture: Kieran McCarthy)

964b. Coventry Irish Society stalwarts Simon McCarthy and Kay Forrest with Cllr Kieran McCarthy at the launch of Irish Heart, Coventry Home last March 2018 (source: Coventry Irish Society)

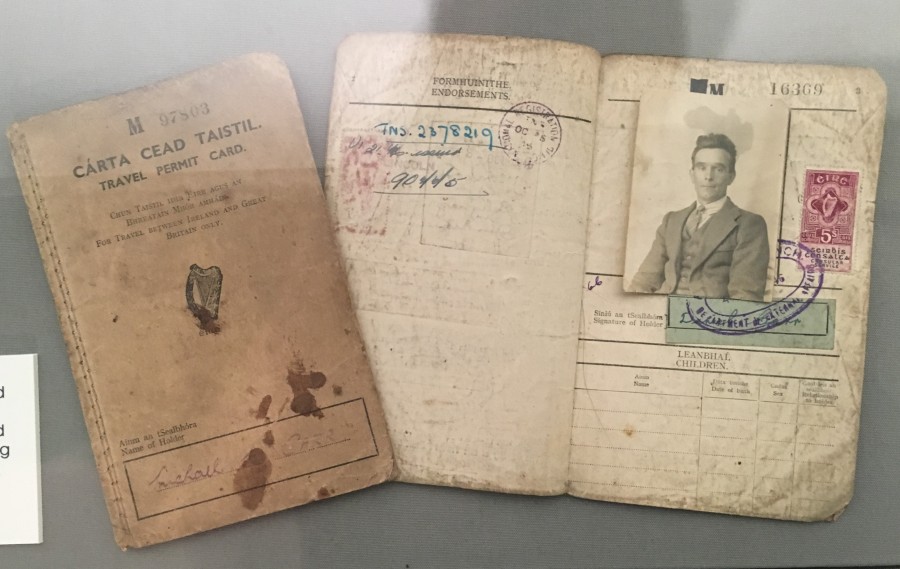

964c. Irish Emigrant Travel Permit Card between Britain and Ireland, 1946 (source: Coventry Irish Society)

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 13 September 2018