Kieran’s Article, Our City, Our Town,

Cork Independent – 7 October 2010

In the Footsteps of St. Finbarre (Part 231)

At the Sword of Light

The quest in the last couple of weeks to write about the heritage of War of Independence memorials, such as the Ballycanon one and that of the Patrick Murphy Civil War memorial, has led to a series of individuals and groups contacting me wishing to elaborate on and debate the historical record. Many have drawn on collective memories that have been passed down and have also presented primary and secondary sources on the topics I have explored in the column.

Recently, I met up with Des O’Grady, an avid local historian, with the Cork based Phoenix Historical Society. He and the society record the people and narratives attached to memorials remembering the Irish War of Independence and the Civil War. We met under the shadow of the iconically carved An Claidheamh Solais sculpture within the Republican Plot at St Finbarre’s Cemetery. This cemetery contains one of the largest burial plots of Irish Republicans who died in the course of the struggle for Irish freedom, most of them during the 1920s but there are some from the late twentieth century as well.

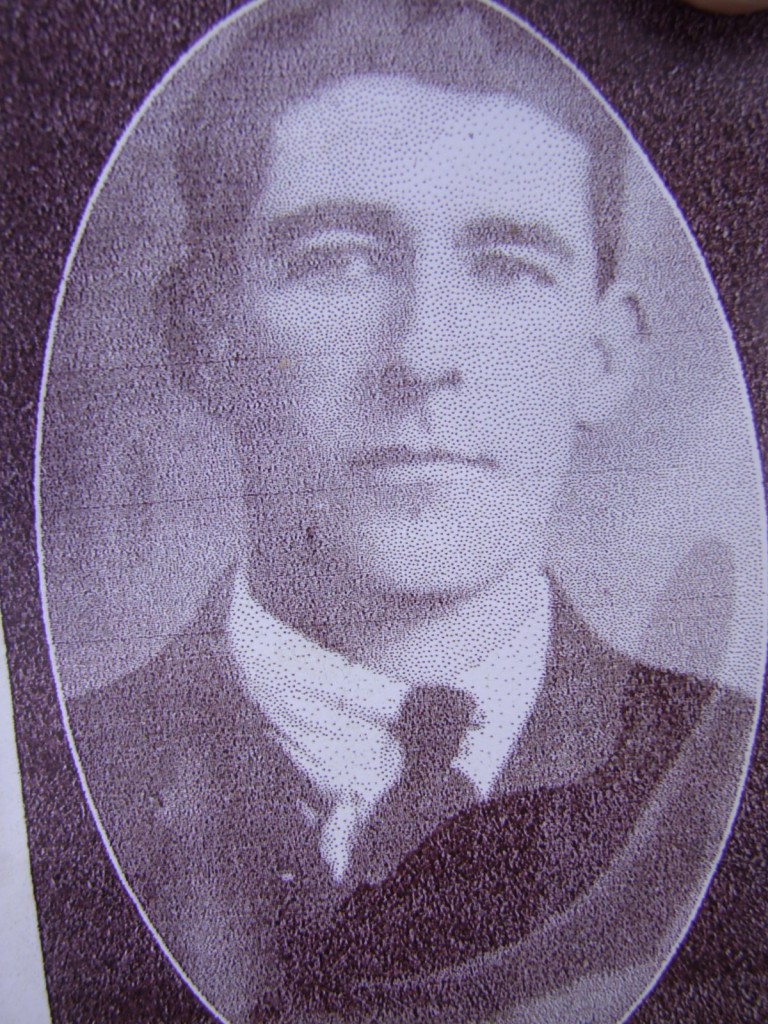

Des outlined his work and thoughts on Patrick Murphy, who is also buried within the plot and whose grave is marked by a stone cross. Patrick was from Model Farm Road at Ministers Cross and the ruin of the 2 storey house, where he was born and bred, can still be seen there. According to the 1911 census, his father was Thomas (a farmer) and his mother was Kate. Patrick was the second youngest in the family being 18 at the time of the census. His sisters were Anne Marie, Queenie and Helena whilst he had one brother Thomas.

Volunteer Patrick Murphy was a member of H Company, First Battalion, First Cork Brigade, Irish Republican Army. The company was formed circa 1917 and comprised members of volunteers living in Glasheen, Bishopstown, Western Road and westwards to Carrigrohane townland. During the War of Independence, the H-Company had failures and successes. In one instance at Ballynacarriga or Inchigaggin Bridge, in an attempt to secure gelignite, an explosive, using in quarries in the areas, they were outgunned by British troops and forced to retreat. In more successful attempts, they captured two British troop lorries at Dennehy’s Cross, Cork City and burned them out. They were also involved in attacks and the burning out of Royal Irish Constabulary police barracks at Bannow Bridge near the Angler’s Rest and at Victoria Cross respectively.

During the Civil War, Patrick took the republican side. The passed down collective memory of his life highlights that Patrick was active in a Flying Column operating in the Inniscarra/ Blarney are and was involved in several operations, including the blowing up of Bannow Bridge at Leemount four days before his death. He was also involved in the raid on the Muskerry Tram on 8 September, with the Flying Column, who were looking for Free State soldiers, who were working undercover in the area. After the column searched all the passengers and the mail bags, they discovered that a Free State agent, hired to kill Sean Mitchell, who was Officer in Command, would pass through the Leemount area at about 11.30am, the following morning. At the time the Free State agent was planning to infiltrate the column posing as an IRA man wishing to get in contact with the column to offer his services. (Countering the Cork Examiner view of the narrative) The Officer in Command, Sean Mitchell and Volunteer O’Sullivan, Patrick Murphy went to Lee Mount Cross on the 9th September to arrest, disarm and interrogate the Free State agent. The gathering of Free State agents encountered opened fire on the latter persons. In the event, Patrick was shot in the stomach. He died of his wounds on 11 September, two days later in the Mercy Hospital.

Patrick Murphy’s grave lies perhaps in one of the most sacred of plots in Cork’s cemeteries, the Republican Plot but perhaps also one of the most contested of Cork’s historical spaces. Indeed it is difficult to write about this great space without encountering different arguments and debates on what traits and deeds of those who fought for Irish freedom should be remembered. However standing in the middle of the plot, I was impressed by the carved An Claidheamh Solais or the Sword of Light, which is also depicted on Patrick Murphy’s memorial and many others, connecting a large series of memorials together. The work in one sense recalls the work of Padraig Pearse, a signatory of the Irish Proclamation of Independence but also an enthusiastic member of the Gaelic League, He was also editor of the League’s newspaper An Claidheamh Solais (The Sword of Light). However, this narrative seems to also be transcended when one looks at this depiction of an ancient sword. Here is a memorial that also seems to carry much symbolism of the early historical journey of the Irish state, a society within a country who fought physically and emotionally with Britain and itself. In essence, here is a powerful sculpture linked to national identity, national memory and political agendas, all very important parts of Ireland’s cultural heritage.

My thanks to Des O’Grady for his patience, courtesy and contribution

To be continued…

Captions:

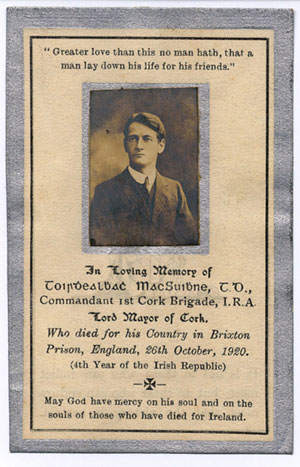

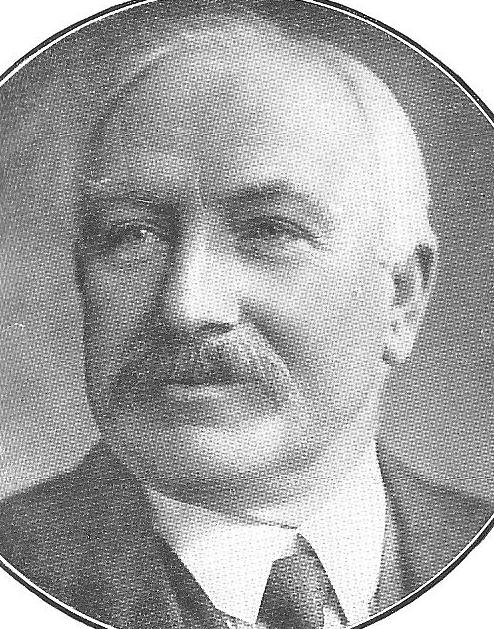

560a. Photograph of Patrick Murphy (picture: Phoenix Historical Society)

560b. Grave of Patrick Murphy, Republican Plot, St. Finbarre’s Cemetery, Cork (picture: Kieran McCarthy)

However I would strongly argue that much of Terence’s key works, his writings, perceptions and learning from his legacy are almost forgotten in the public realm. He was one of the founders of the Cork Brigade of the Irish volunteers. His hunger strike brought international attention to the Irish War of Independence plus created an international debate on the ongoing war. His book Principles of Freedom inspired many in India to rise up against British control in the late 1920s and 1930s. He was also a playwright, poet, founder of the Cork Dramatic Society with another of Cork’s famous literary sons Daniel Corkery. Terence wrote five plays with themes around revolution, democracy and freedom.

However I would strongly argue that much of Terence’s key works, his writings, perceptions and learning from his legacy are almost forgotten in the public realm. He was one of the founders of the Cork Brigade of the Irish volunteers. His hunger strike brought international attention to the Irish War of Independence plus created an international debate on the ongoing war. His book Principles of Freedom inspired many in India to rise up against British control in the late 1920s and 1930s. He was also a playwright, poet, founder of the Cork Dramatic Society with another of Cork’s famous literary sons Daniel Corkery. Terence wrote five plays with themes around revolution, democracy and freedom.