Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 14 April 2011

History Tour of St. Finbarr’s Hospital

Next Saturday morning, 16 April at 11am in association with Turners Cross Community Association for the Lifelong Learning Festival, I will conduct a historical walking tour of St. Finbarr’s Hospital (meet at gate). In one sense, this article is another aside article to the Lee but that being said, how one attempts to work through a heritage site and what memories should a researcher focus in on the modern world are all issues that again and again frequent my research.

This time round there is also the added issue of me living in the area and the fact that every day of my life, I have passed the hospital. I have always admired the view from the entrance gate onto the rolling topography extending to beyond the southern boundaries of the City. Here also is the intersection of the built heritage of Turners Cross, Ballinlough and Douglas. These are Cork’s self sufficient, confident and settled suburbs, which encompass former traditions of market gardening to Victorian and Edwardian housing on the Douglas Road. Then there is the Free State private housing by the Bradley Brothers such as in Ballinlough and Cork Corporation’s social housing developments, designed by Daniel Levie, on Capwell Road. Douglas Road as a routeway has seen many changes over the centuries from being a rough trackway probably to begin with to the gauntlet it has become today during the work and school start and finish hours.

However for all of what I have said I can argue that all of the above memories and mixed histories make these areas places of experiment in their time of creation– the erection of stately red bricked 1880s housing on roads like Cross Douglas Road started a trend to build new suburbs for the middle class just outside the city boundary in the late 1800s. In more recent times I have become more intrigued studying the affects of Free State Ireland and the aspirations of events like the Irish Industrial and Agricultural Fair in 1932- those aspirations for creating a better Ireland and in Cork the movement of people from the inner city slums to new housing estates like Capwell. Capwell’s post office and its sign 1926 is of change in that time not to mention Barry Byrne’s designed Christ the King Church, an imposing monument in itself to honour change and also to Cork’s continuously outward looking vision to the world. In this case, go google Church of Christ the King, Tulsa Oklahoma to see what the Turners Cross is modelled on.

Standing at the gate of St. Finbarre’s Hospital reflecting on all the above histories and memories above begs the question on how do you even blend these in to a tour without leaving your audience behind. With mid nineteenth century roots, the hospital was the site of the city’s former workhouse but as such here is one of Cork’s and Ireland’s national historic markers. Written in depth over the years by scholars such as Sr. M. Emmanuel Browne and Colman O’Mahony, what has survived to outline the history of the hospital are many indepth primary documents. What shines out are the memories of how people have struggled at this site since its creation in 1841. Other topics perhaps can also be pursued here such as the history of social justice at the site, why and how society takes care of the vulnerable in society and the framing of questions on ideas of giving humanity and dignity to people and how they have evolved over the centuries.

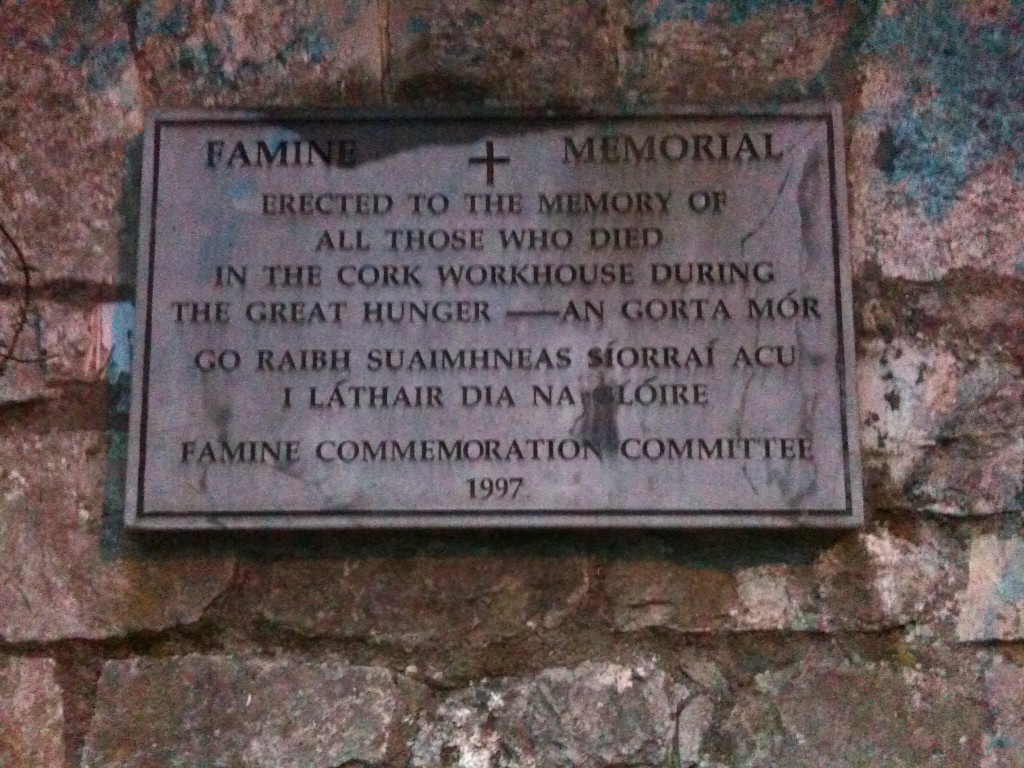

The key feature of this new tour or trail is the story of the hospital and an attempt to unravel its memories. The Hospital serves as a vast repository of memories, symbolism, iconography and cultural debate. It has plaques, ruins and haunted memories. Standing at the former workhouse buildings, which opened in December 1841, there is much to think about – humanity and the human experience. The architect to the Poor Law Commissioners in Ireland from 1839 until 1855 was George Wilkinson. Nearly all the workhouses, accommodating between 200 and 2000 persons apiece, were designed in a Tudor domestic idiom, with picturesque gabled entrance buildings which contracted the size and comfortlessness of the institutions which lay behind them. By April 1847 all 130 workhouses were complete, the Douglas Road being one of the first.

With its association with the memory of the Great Famine, there are also many threads of the history of the hospital to interweave – the political, economic and social framework of Ireland at that time plus the on the ground reality of life in the early 1800s – family, cultural contexts, individual portraits. In the present day history books in school, the reader is drawn to very traumatic terms. The recurring visions comprise human destruction, trauma, devastation, loss. One can see why the Great Famine is more on the forgetting list than on the remembering one.

The walking tour next Saturday is an attempt to unravel some of the memories of the workhouse, how also it evolved into the present day hospital and also connect it into the history of the wider area.

Captions:

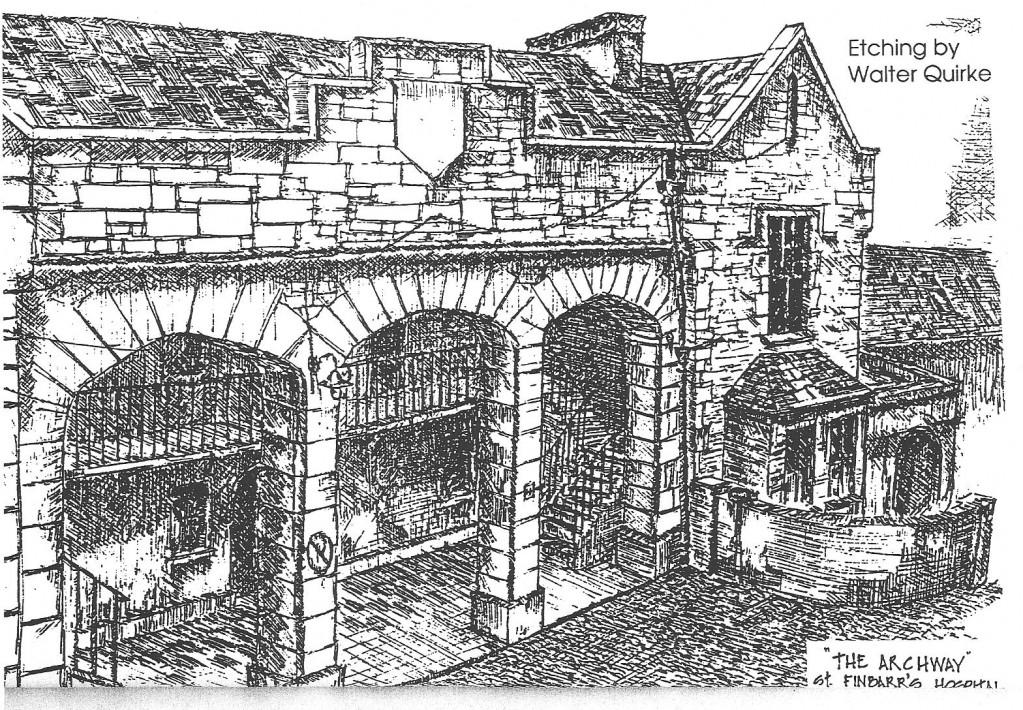

586a. Sketch of former workhouse building, St. Finbarr’s Hospital (source: Walter Quirke)

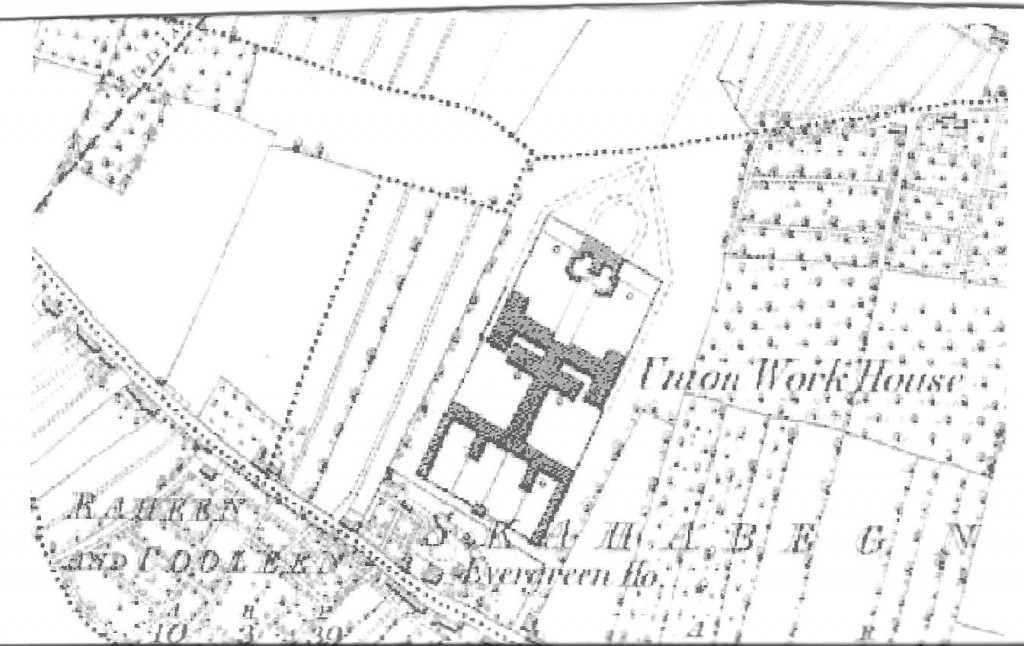

586b. Section of Ordnance Survey Map, c.1846 showing the Union Workhouse, Douglas Road (source: Cork City Library)

Many thanks to everyone for turning out here this evening.

Many thanks to everyone for turning out here this evening.  I admire greatly what Hincks achieved and ultimately his legacy, the legacy of the Royal Cork Institution. In particular, the ideas of education and its value, how he drove that…

I admire greatly what Hincks achieved and ultimately his legacy, the legacy of the Royal Cork Institution. In particular, the ideas of education and its value, how he drove that…